Fiscal Policy For An Unprecedented Crisis – Analysis

By Vitor Gaspar, Paulo Medas, John Ralyea and Elif Ture

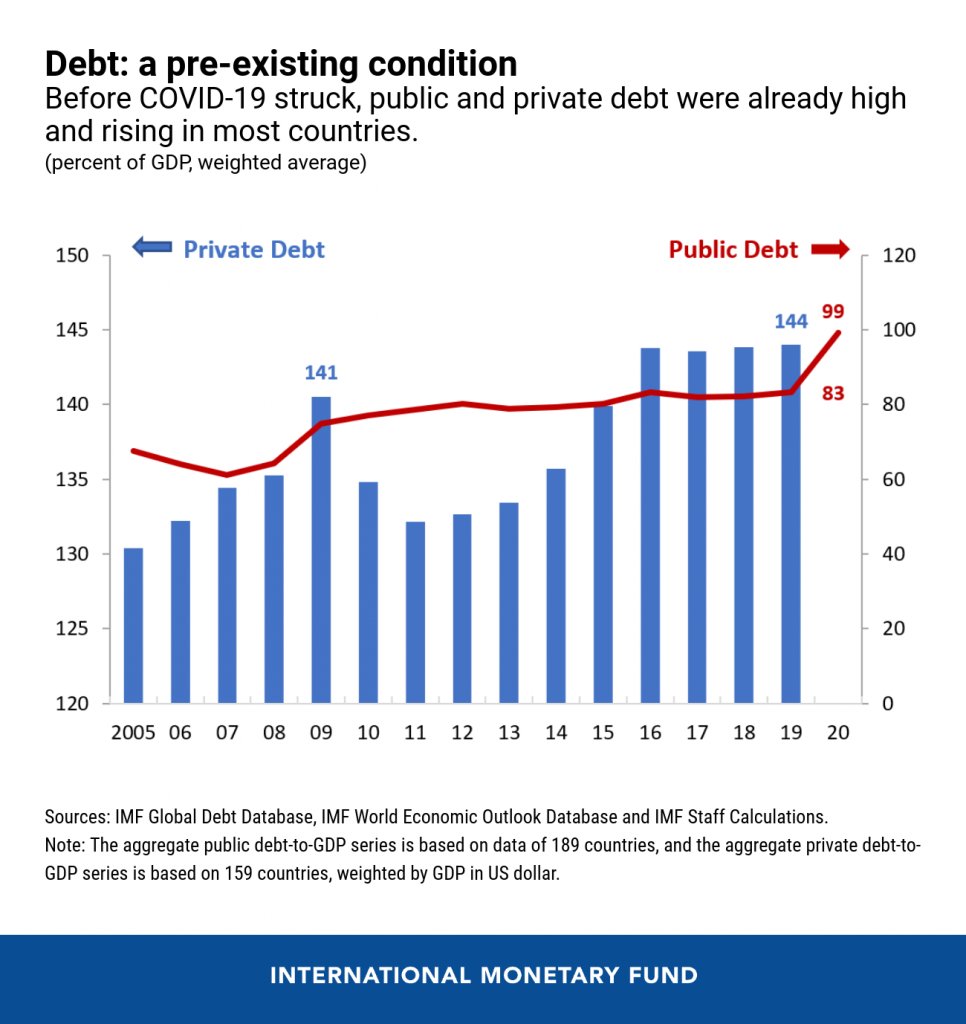

The COVID-19 crisis has devastated people’s lives, jobs, and businesses. Governments have taken forceful measures to cushion the blow, totaling a staggering $12 trillion globally. These lifelines have saved lives and livelihoods. But they are costly and, together with sharp falls in tax revenues owing to the recession, they have pushed global public debt to an all-time high of close to 100 percent of GDP.

With many workers still unemployed, small businesses struggling, and 80‑90 million people likely to fall into extreme poverty in 2020 as a result of the pandemic—even after additional social assistance—it is too early for governments to remove the exceptional support. Yet many countries will need to do more with less, given increasingly tight budget constraints.

The October 2020 Fiscal Monitor examines countries’ experiences managing the crisis and discusses what governments can do in the different phases of the pandemic to save lives, reduce the impact of the recession, and revive growth and job creation.

Policies during the lockdown phase

Since the start of the COVID-19 crisis, governments have focused on doing whatever it takes to limit its consequences. The massive fiscal support provided since the start of the COVID-19 crisis has succeeded in protecting people and preserving jobs.

Public health measures that have contained the spread of the virus—such as large-scale testing, tracing, and public information campaigns—have helped restore confidence and created the conditions for the safe reopening of businesses.

Unemployment benefits and wages subsidies (as in most European economies) have helped preserve jobs or living standards. Cash transfers have been especially useful to support the poor and informal workers and self-employed who lost jobs. Liquidity support to firms have prevented a wave of defaults and mass layoffs. This is especially important for small-and medium-sized firms that represent a large share of employment.

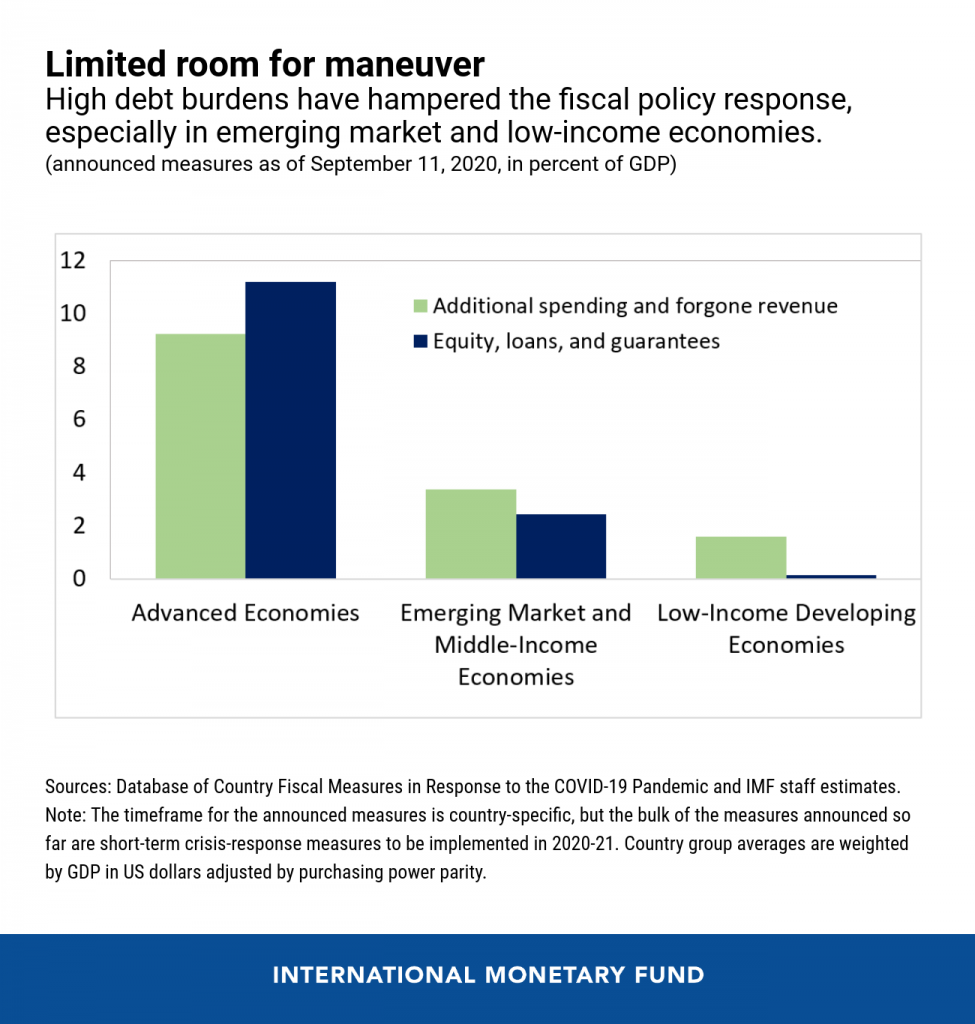

Although the global fiscal response to the crisis has been unprecedented, responses by individual countries have been shaped by their access to borrowing as well as their public and private debt levels heading into the crisis.

In advanced economies and some emerging market economies, central bank purchases of government debt have helped keep interest rates at historic lows and supported government borrowing. In these economies, the fiscal response to the crisis has been massive.

In many highly indebted emerging market and low-income economies, however, governments have had limited space to increase borrowing, which has hampered their ability to scale up support to those most affected by the crisis. These governments face tough choices.

A fiscal roadmap for the recovery

As economies tentatively reopen, but uncertainty about the course of the pandemic remains, governments should ensure that fiscal support is not withdrawn too rapidly. However, it should become more selective and avoid standing in the way of necessary sectoral reallocations as activity resumes. Support should shift gradually from protecting old jobs to getting people back to work—for example, by reducing job retention programs (wage subsidies), reintroducing job search requirements, and training new skills—and helping viable but still-vulnerable firms safely reopen. With low interest rates and high unemployment, boosting public investment—starting with maintenance and ramping up projects—can create jobs and spur economic growth.

Emerging market and low-income economies facing tight financing constraints will need to deliver more with less, by reprioritizing spending and enhancing its efficiency. Some may need further official financial support and debt relief.

Governments should also adopt measures to improve tax compliance and consider higher taxes for the more affluent groups and highly profitable firms. The ensuing revenues would help pay for critical services, such as health and social safety nets, during a crisis that has disproportionately hurt the poorer segments of society.

Once the pandemic is under control, governments will need to foster the recovery while addressing the legacies of the crisis—including the large fiscal deficits and high public debt levels.

- Countries with fiscal space and major scarring from the crisis, such as large long-term unemployment, should provide temporary fiscal stimulus while planning for an adjustment over the medium term.

- Countries with high debt levels and less access to financing will also need to adjust over the medium term, striving to protect public investment and transfers to lower-income households.

The post-pandemic reset

Looking ahead, countries will need to make it a priority to invest in healthcare systems and education. They should also strengthen social safety nets to ensure that all people have access to food and other basic goods and services.

As economies begin to recover, governments should seize this moment to move away from the pre-crisis growth model and accelerate the transition to a low-carbon and digital economy. Carbon pricing should be a key feature of this transition, because it encourages people to reduce energy use and shift to cleaner alternatives—and, moreover, it generates revenue that can be used in part to support the most vulnerable.

As governments ramp up their public investment and other fiscal measures to foster the recovery, their policy choices will have long-lasting effects. They should make a decisive push to make economies more inclusive and resilient, and to curb global warming through green measures that also boost growth and employment.

*About the authors:

- Vitor Gaspar, a Portuguese national, is Director of the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department. Prior to joining the IMF, he held a variety of senior policy positions in Banco de Portugal, including most recently as Special Adviser. He served as Minister of State and Finance of Portugal during 2011–2013. He was head of the European Commission’s Bureau of European Policy Advisers during 2007–2010, and director-general of research at the European Central Bank from 1998 to 2004. Mr. Gaspar holds a PhD and a post-doctoral agregado in Economics from Universidade Nova de Lisboa. He has also studied at Universidade Católica Portuguesa.

- Paulo Medas is Deputy Division Chief in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department. Previously, he held various positions in the IMF’s European and Western Hemisphere departments. He was the IMF’s Resident Representative in Brazil from 2008-11. He has led capacity building missions to several countries. His areas of research include governance and corruption, fiscal crises, and management of natural resources. He was one of the co-authors in the recent book Brazil: Boom, Bust, and Road to Recovery.

- John Ralyea is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department. Previously, he worked in the IMF’s European department, with stints on the Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain teams, and in the Finance department. He has conducted research related to fiscal risks including state-owned enterprises, public pensions, and fiscal rules. Prior to joining the IMF, John worked for the U.S. Treasury Department. He holds a Masters degree from the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. In another life, John was a Certified Public Accountant.

- Elif Ture, from Turkey, is an economist in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department (FAD), where she works on European fiscal issues as part of the euro area team and contributes to the Fiscal Monitor. In FAD, she has worked on fiscal risks from contingent liabilities, fiscal rules, fiscal federalism, and fiscal governance in Europe. She was previously an economist in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department, where she conducted policy and analytical work on sustaining strong and inclusive growth in the Southern Cone economies. Her research areas include financial sector imperfections and macro-financial linkages. She holds an economics PhD from the University of Maryland at College Park.

Source: This article was published in the IMF’s Blog