Russian Drones: What Has Gone Wrong? – Analysis

By Pavel Luzin*

Since the beginning of its large-scale aggression against Ukraine, Russia has demonstrated relatively poor capabilities regarding its unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), much poorer than one would expect given the extensive resources Moscow has dedicated to this aspect of its military. Throughout the past 12 years, Russia has invested heavily into developing and purchasing all spectrums of military UAVs: from reconnaissance and targeting drones to electronic warfare and combat-capable ones coupled with loitering munitions.

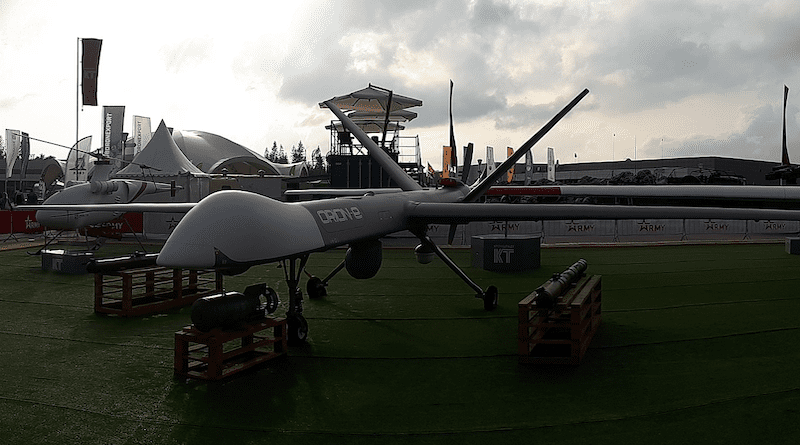

Nevertheless, the Russian Armed Forces, early on, faced a severe deficit of reconnaissance UAVs after just several months of fighting against Ukraine. Most likely, this deficit was apparent even on the eve of the invasion, but the massive losses since have further exacerbated the situation. Overall, we have seen several instances of Russian forces using the Russian-made loitering munitions Lancet and KUB-BLA (Life.ru, November 9) and only a couple less-effective examples of them using Orion combat drones (UNIAN, April 9; EurAsia Daily, October 21).

As a result of this deficit, hundreds of Chinese-made commercial drones (including different models of the DJI Mavic) have been purchased by volunteers from various Russian regions (Ura.news, October 10). The Russian government itself has purchased hundreds of Iranian-made loitering munitions and drones. Nevertheless, the infusion of these supplies has not changed the situation on the battlefield. And the lack of necessary electronics and technologies, coupled with a dependence on imported components, are only a few of the causes here. Other and even more significant causes lie in Russia’s political-economic system, the specific issues with its defense industry and the spreading of limited resources among too many projects.

Most Russian developers and manufacturers of military UAVs are formally private companies among the huge state-owned defense corporations: Special Technology Center (Orlan-10 UAV, which is used for artillery tactical reconnaissance and within the electronic warfare system Leer-3); Kronshtadt (Orion drones); Zala Aero Group (the small tactical reconnaissance drones and loitering munitions Lancet and KUB-BLA); and UZGA (Altius/Altair project for heavy UAVs). However, these entities were either affiliated with the Russian military from the start, such as the Special Technology Center, whose owners are directly affiliated with the Russian Armed Forces (Vas.mil.ru, October 2022, November 2022), or were merged with those companies directly or indirectly affiliated with the state-owned defense corporations and the Russian government.

These companies relied on global supply chains for certain electronics, other components (often consumer-grade), engines and industrial equipment. Moreover, the most advanced Russian reconnaissance UAV, Forpost, is a licensed copy of the Israeli UAV IAI Searcher. After the annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the war in Donbas in 2014, the development of Russian UAVs has become slower and plagued with increased maintenance issues. For instance, early on, the Orlan-10 UAV appeared to be much more robust than originally planned, and this partly compensates for the absence of proper technical maintenance (Cast.ru, accessed November 10). Additionally, the Altius project appeared to be too sophisticated for developers (Business-gazeta.ru, October 9, 2018; RIA Novosti, June 25, 2021), and it was not even ready for testing in active combat after the Russian re-invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

In addition, state-owned defense corporations, including Rostec and United Aircraft Corporation (which now belongs to Rostec), tried to develop UAVs on their own, initiating the Korsar and S-70 projects, respectively (Rostec, July 15, 2019; UAC, December 14, 2021). However, it seems the Korsar test units have already been lost in Ukraine (Focus.ua, November 10), and the S-70 is far from operational, despite a decade of development (TASS, August 16, 20).

The Russian combat drones are represented solely by the Orion UAVs, but the main problem with this UAV is the absence of serial manufacturing. The production factory was only recently completed at the end of 2021, and its projected annual manufacturing capacity is a mere 45 UAVs (RIA Novosti, August 20, 2021). However, as of July 2022, the factory was still rather far from realizing its planned capacity (Indubnacity.ru, July 4). Therefore, the Orion drones will be less present on the battlefield for the foreseeable future.

Presumably, the situation with manufacturing loitering munitions in Russia is almost the same: the serial manufacturing of Lancet and KUB-BLA units is rather limited (Vedomosti, October 24). The current annual manufacturing rate may be estimated at 50–60 units—but certainly not in the hundreds nor thousands.

Moreover, considering the losses of Orlan-10 and other drones, Russia now faces the trouble of restoring its stock of UAVs, and it is not clear whether the existing factories will be capable of handling the mass production of replacement systems (Dp.ru, October 14). All this means that Moscow’s previous approach toward UAV development was far from efficient.

Regarding drones, Russia has tried to become an equal with the United States and Israel, but instead, its UAV industry appears to be weaker than that of Turkey. In truth, Russia’s UAV development is fraught with problems because Moscow has attempted to spread limited resources among too many project and has tried to control UAV developers, rather than stimulating private initiative and improving the overall toxic institutional environment. Although, in this regard, even private initiatives will not be enough, considering the Western embargo on supplies of critical technologies, components and industrial equipment in Russia.

Nevertheless, Moscow will continue all its military UAV projects for as long as possible. Most likely, the Kremlin will even redistribute resources from other arms procurements in favor of UAVs. Russian officials are also placing hopes on smuggling, industrial espionage and circumventing sanctions through Russia’s allies. These efforts are likely to be too insufficient, but they can still give Moscow an opportunity to learn some lessons and restore some of its military power, aiming to start the next phase of the war, especially if there is a stalemate on the battlefield.

*About the author: Dr. Pavel Luzin is a visiting scholar at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University. He is also a regular contributor at The Jamestown Foundation, Riddle and the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He is a specialist in international relations and an expert on the Russian Armed Forces. Much of his research and writings focus on Russian foreign policy and defense, space policy and non-proliferation studies.

Source: This article was published by The Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 19 Issue: 169

Very well researched article but it leaves out a fundamental question regarding all Russian arms manufacturing: corruption and looting of resources by oligarchs and others.