The Bank Of Japan At The Policy Frontier – Analysis

By VoxEU.org

The Bank of Japan has recently implemented one of the largest central bank policy shifts in modern times, raising its inflation target explicitly to 2% and kicking off the most rapid balance sheet expansion among the leading central banks. This column assesses this policy decision and its potential pitfalls, and compares it to similar policies enacted in the past. Unless policy has a significantly larger impact on financial conditions going forward than it has to date, the revised framework will likely be insufficient to achieve the Bank’s inflation target any time soon.

By Stephen Cecchetti and Kim Schoenholtz*

Since Governor Haruhiko Kuroda took office in March 2013, the Bank of Japan has been the most aggressively expansionary advanced-economy central bank. Its September announcement of a “new framework for strengthening monetary easing” — coming only six months after introducing negative policy rates — distances it even further from the pack.

That a central bank is willing to assess its performance transparently and to consider new approaches to achieving its key goals is something we have come to expect. While it’s too early to tell whether the latest Bank of Japan innovations will be more successful, there is reason to be sceptical. No less important, the new approach involves risks to the central bank and to financial market stability that may not be fully appreciated. Given the difficulties that other advanced-economy central banks seem to be having in raising inflation and inflation expectations, how the Bank of Japan fares is of interest far beyond Japan.

Facing a challenging environment

The Bank of Japan’s policy challenge stands out because, after a generation of falling prices, deflationary expectations were deeply embedded when Mr Kuroda became governor in early 2013. Moreover, businesses and households correctly anticipated that the need to control the country’s rapidly rising sovereign debt would lead to many years of fiscal restraint.

Confronted with this very challenging environment, in March 2013 the Bank of Japan implemented one of the largest central bank policy shifts in modern times, raising the Bank’s inflation target explicitly to 2% and kicking off the most rapid balance sheet expansion among the leading central banks. It was and remains a radical experiment in expectations management. Since the policy change, the Bank of Japan’s holdings of Japanese Government bonds (JGBs)—its largest asset—have jumped by nearly a factor of four, rising from 11% to 37% of total JGBs outstanding. And, the central bank currently still aims to increase its holdings by about ¥80 trillion annually—about 16% of nominal GDP and far in excess of annual JGB issuance. This means that by late 2017, Bank of Japan assets will reach 100% of Japanese GDP.

Deflation did turn to inflation, at least for a while. But as of September 2016, core CPI inflation (measured by the trimmed mean CPI) was back at -0.1%, barely above the -0.3% recorded before Governor Kuroda took office. Not only that, but after having initially risen following the April 2013 original implementation of ‘quantitative and qualitative monetary easing’ (QQE), measures of long-term inflation expectations have receded, in some cases sharply. For example, after peaking at nearly 1.4% in mid-2015, the five-year-forward five-year inflation swap rate is now about 0.3%, only modestly above the level before Shinzo Abe became Prime Minister in December 2012 (see Figure 1). Perhaps most disheartening is the plunge in early 2016 – over the month following the Bank of Japan’s announcement of its negative interest rate policy on 29 January, the Japanese inflation swap rate declined from nearly 0.5% to zero. Despite the supportive US election shock that depressed the yen, it remains below the pre-29 January range.

Figure 1. Five-year-ahead, five-year Japan inflation swap rate, 2012-28 November 2016

The September 2016 policy framework

Against this background, the Bank of Japan undertook a ‘comprehensive assessment’ of economic conditions and the impact of monetary policy, issuing its conclusions in September 2016. The new framework – dubbed ‘quantitative and qualitative monetary easing with yield curve control’—includes two key policy shifts: (1) the introduction of a target level for the 10-year JGB yield of around 0%; and (2) a commitment to continue expanding its balance sheet until inflation (measured by the CPI less fresh food) exceeds 2% and “stays above the target in a stable manner”.

What should we make of this? What do these new commitments mean? Will they be effective in raising inflation expectations and inflation?

Let’s start with the second part—the ‘overshooting’ commitment. One of the Bank of Japan’s challenges is to overcome the damage the decades-long deflation has done to its credibility. The promise to overshoot the 2% inflation target is a form of state-contingent forward guidance designed to bolster the perception of the central bank’s policy commitment in the minds of those setting wages and prices. The commitment comes with a clarification of the Bank of Japan’s definition of price stability: namely, “attaining a situation where the inflation rate is 2% on average over the business cycle” (our emphasis).

This version of inflation targeting shares key features of a price-level or nominal GDP target. Advocates of the latter frameworks (e.g. Woodford 2014) view them in part as devices that can lower the expected real interest rate at the effective lower interest rate bound (ELB). With a price-level target, for example, sub-target inflation is expected to be followed by above-target inflation. That is, policymakers are committed to make up for lost ground rather than (as in the case with many forms of inflation targeting) ignore past misses. So, imagine a situation in which a central bank has a 2% inflation target, but actual inflation has been 0% for two years and the interest rate is at the ELB (modestly below 0%). With an inflation target, the real interest rate cannot go much below -2%. But instead, if the central bank has a credible price level target, people will expect inflation to rise temporarily to 4%, so the real interest rate can fall to -4%.

It is possible that the new strategy could lead inflation expectations to rise above 2%, reversing the deflationary Japanese mindset once and for all. Unfortunately, experience is not on the Bank of Japan’s side. Absent other economic and policy changes, it is unclear why continuous expansion of the central bank balance sheet alone will have a significantly greater impact either on expectations or on the plans of wage- and price-setters going forward than it has had in the past. The best hope is that a tighter labour market—arguably the tightest in 25 years—eventually will lead to faster wage gains.

Yield-curve control

How about ‘yield-curve control’ and the new 10-year JGB yield objective? Economists have long viewed the introduction of a target for a government bond yield (rather than an overnight rate) as one of the most unconventional of unconventional monetary policy tools. Then Federal Reserve Governor Ben Bernanke expressed a preference for this approach in his famous 2002 talk about tools to prevent or address deflation (see Bernanke 2002). A decade later, Ball (2012) asked why Chairman Bernanke chose not to use this tool.

When targeting a bond (of anything but an extremely short maturity), a central bank can determine either the price or the quantity, but not both. One reason for the Fed’s focus on quantity rather than price is that targeting a long-term government bond yield raises risks of balance sheet instability, something highlighted in a recently-released 2010 Federal Reserve staff memo (FOMC Secretariat 2010). To understand why, it is important to realise that targeting the yield means offering to buy and sell the long bond in unlimited quantities. As the Fed memo notes, if investors suspect that the central bank is going to raise its yield target, thereby driving down the price of the bond, there will be a rush to sell and a massive expansion of the central bank balance sheet.

With regard to the loss of balance sheet control, a useful recent analogy is the Swiss National Bank’s effort from September 2011 to January 2015 to cap the Swiss franc versus the euro (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2015). The SNB committed itself to acquire euros without limit, making the size of its balance sheet endogenous. However, doubts about the commitment, reflecting financial disruptions in the euro area, the advent of quantitative easing by the ECB, and Swiss political concerns about the potential losses on SNB holdings of euros, meant that the SNB had to acquire a massive volume of euros—as much as 70% of GDP—to maintain its commitment. As a result, when it reneged on the commitment in 2015, the SNB experienced large capital losses.

No less important, by making its balance sheet endogenous, a central bank that targets a government bond yield passes monetary control to the fiscal authorities, who decide how much of the yield-targeted instrument to issue. The most well-known central bank experience with targeting longer-maturity government debt was the Fed’s commitment to cap the US Treasury yield curve beginning in 1942. The yield curve pledge facilitated wartime finance. Following WWII, however, inflation reached double-digit levels during 1947 and 1948. It wasn’t until the Treasury Accord of 1951—amid inflationary pressures from the Korean War—that the Fed was able to exit this commitment, and only after open confrontation between the Fed and the Treasury (see Hetzel and Leach 2001).

Following the Bank of Japan’s 21 September 2016 announcement, there was some uncertainty about whether it would make its balance sheet fully responsive to changes in government bond issuance and private demand for 10-year JGBs, partly because of its unchanged plans to acquire JGBs at an ¥80 trillion annual rate. However, in an October speech and discussion, Governor Kuroda made clear that the commitment to yield curve control means that the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet will be endogenous (see Kuroda 2016, Kuroda and Wessel 2016). He also argued that the Bank of Japan retained independent monetary control because it can revise the yield target at any time. We are sceptical, as targeting flexibility could easily aggravate market instability. As we already noted, any suspicion that the central bank will alter its yield target could trigger massive private sales or purchases.

Is the new policy working?

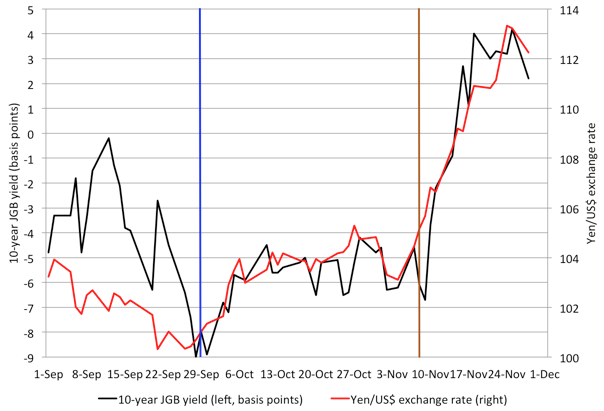

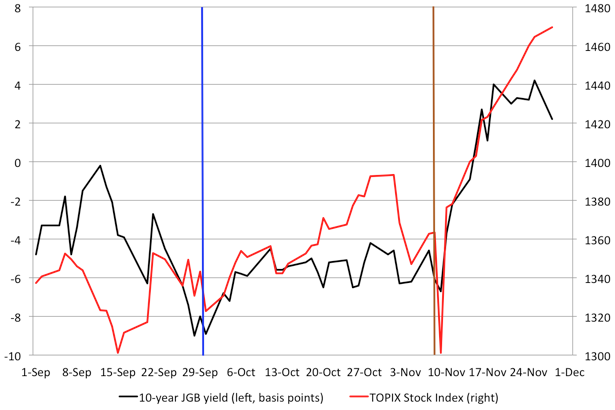

So, has the Bank of Japan’s policy worked? Figure 2 below suggests that the revised policy framework has been mildly stimulative for financial conditions. As of November 28th, the 10-year JGB yield has been capped close to zero (as the Bank of Japan promised), while the US elections ushered in a period of yen depreciation and rising equity prices. That said, the yen is still 7% stronger versus the US dollar than it was on average in 2015, while the stock market is down by 5%.

Figure 2.

a. Japan: 10-year JGB yield (basis points) and the Yen-U.S. dollar exchange rate, September 1-November 28, 2016

b. Japan: 10-year JGB yield (basis points) and the TOPIX Index, September 1-November 28, 2016

The bottom line

Our bottom line is that, by making their balance sheet endogenous, the September 2016 Bank of Japan policy framework of yield curve control is potentially more aggressive than previous incarnations of QQE, either the original or the one with negative rates. However, unless policy has a significantly larger impact on financial conditions going forward than it has thus far, the revised framework is likely to remain insufficient to achieve the central bank’s inflation target any time soon.

What’s left in the monetary policy toolbox that has not been tried? Not much. As the Bank of Japan balance sheet ballooned, officials also broadened the scope of asset purchases to include private bonds and equity, and lowered the policy rate below zero. Having now shifted toward a framework akin to price-level targeting and targeted a zero yield on the 10-year JGB, we see only one significant tool remaining: an explicit exchange rate target aimed at keeping the yen at least slightly undervalued – what Lars Svensson (2003) described as the “foolproof way” to raise inflation. But, in the case of a large, mature economy like Japan, explicitly promoting yen depreciation would be viewed as extremely unfriendly and could easily trigger protectionist retaliation.

Authors’ note: An earlier version of this post appeared on www.moneyandbanking.com. We are grateful to Jeffrey Young for his very helpful suggestions.

*About the authors:

Stephen Cecchetti, Professor of International Economics at the Brandeis International Business School

Kim Schoenholtz, Professor of Management Practice, NYU Stern School of Business

References:

Ball, L M (2012), “Ben Bernanke and the Zero Bound,” NBER Working Paper No. 17836.

Bernanke, B S (2002), “Deflation: Making Sure “It” Doesn’t Happen Here,” remarks before the National Economists Club, Washington, DC, 21 November.

Cecchetti, S G (1988), “The Case of the Negative Nominal Interest Rates: New Estimates of the Term Structure of Interest Rates during the Great Depression,” Journal of Political Economy 96(6): 1111-1141.

Cecchetti, S G, and K L Schoenholtz (2015), “A Swiss Lesson in Time Consistency,” www.moneyandbanking.com, 19 January.

FOMC Secretariat (2010, “Strategies for Targeting Interest Rates Out the Yield Curve,” 13 October (released on 29 January 2016).

Hetzel, R L and R F Leach (2001), “The Treasury-Fed Accord: a Narrative Account,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly 87(1): 33-55.

Kuroda, H (2016), “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) with Yield Curve Control: New Monetary Policy Framework for Overcoming Low Inflation”, speech at the Brookings Institution, 8 October.

Kuroda, H and D Wessel (2016), “A Conversation with Governor Haruhiko Kuroda,” Brookings Institution, 8 October.

Svensson, L E O (2003), “”Escaping From a Liquidity Trap and Deflation: The Foolproof Way and Others,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17(4): 145-166.

Woodford, M (2014), “Monetary Policy Targets after the Crisis,” in G Akerlof, O Blanchard, D Romer and J Stiglitz (eds.), Monetary Policy Targets after the Crisis, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp 55-62.