South Asia: A Strategic Update On Pitfalls, Potentials And Possibilities – Analysis

By Institute of South Asian Studies

South Asia is not a coherent entity. Despite that, the region is not without clout on the international stage. This is due to several factors – India’s sustainable democracy and economic growth, Pakistan’s strides in countering terrorism, Bangladesh’s emerging culture of democratic pluralism and economic performance, and Sri Lanka’s recent peaceful transfer of power and focus on development. This makes for an important role for the region in the global context.

By Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury*

South Asia, which hosts close to one-fourth of humanity, continues to command global attention. However, for some time now, the region has been playing second fiddle to others in Asia ̶ Southeast Asia and China and the Far East ̶ as those parts of the continent transformed themselves faster into becoming part of the world’s economic locomotive. That pace of growth appears to have somewhat slowed, while South Asia has started to reveal its potentials in a sharper fashion. Thus, global attention has become more focussed on the South Asian region.

Region Defined

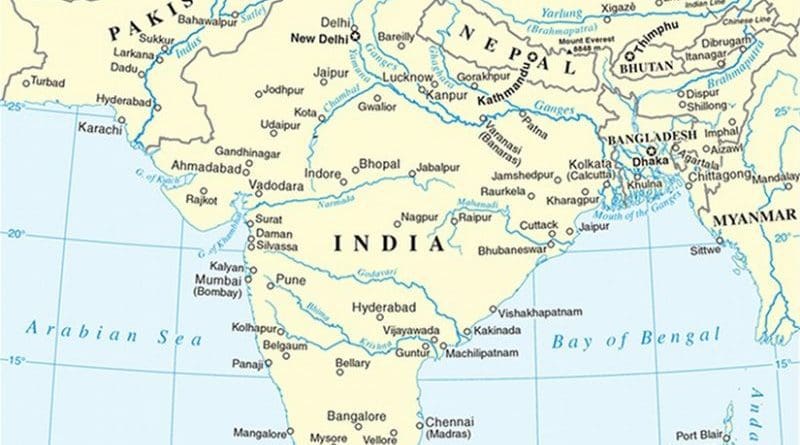

The Classical Greeks used to say, prior to a debate one must define one’s terms. So, should one, with regard to our subject. So, what constitutes South Asia? An easy working definition for South Asia would be that the term refers to the eight countries that are members of the regional South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC): Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. SAARC, which has proved to be minimally useful otherwise, has at least helped define the region, and given the populations a sense of collective identity, of what might otherwise have been only a ‘geographical expression’.

Not a Coherent Entity

Despite the existence of SAARC, the region has not proved to be a coherent entity. It is probably not, economically, politically, socially and strategically. In economic terms, South Asian states do not see one another as effective partners. Less than 5% of their trade is among themselves, a dismal figure compared to other regions. Whenever there has been a commitment to reduce trade barriers, non-trade barriers (NTBs) have emerged as even greater impediments to trade. Commercial intercourse between the two largest neighbours, India and Pakistan, has not exceeded the sum of US$ 3 billion, less than what occurs illegally, or informally, or through Dubai. The concept of a ‘sensitive list’ of trade items has been introduced, which has assumed unhelpful proportions. While the transformation from agriculture to manufacturing and services has been nothing short of remarkable in many of the countries, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka for instance, have turned mainly to Europe, the United States and the Far East for their markets. Especially for the five countries formally listed in the United Nations as Least Developed Countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Maldives until it graduated from the list recently), foreign aid from the US, Europe, Japan, the Gulf and mixed- support from China and the multilateral soft credit windows accounted for the external resources mobilised for development. India and other South Asian countries were peripheral to them in this regard.

Politically, the poor state of inter-country relations appears to have become a permanent feature. Traditionally, the countries of South Asia have defined their sovereign existence in terms of distinctiveness from one another, in particular from India. Thus, the comparatively smaller neighbours have always turned to extra-regional actors, such as Pakistan to the US and then China, to make-up for the power-gap with India. This has exacerbated the negative aspects in regional relations. Apart from the two major protagonists of India and Pakistan, India and Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan, Sri Lanka and India, have had serious issues dividing them. India and Pakistan seem locked into perennial dispute, not only of irredentist nature, such as Kashmir, Siachen and Sir Creek for example, but across a broad range of political and diplomatic issues, preferring to line up on opposite sides on any contested subject in the global arena. Pakistan has been resisting tooth and nail, India’s aspirations for a permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council, and India was not unhappy over Pakistan’s expulsion from the Commonwealth (in 2008). There have been glimmers of hope from time to time, generated by events such as the impromptu visit of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Pakistan in December last year, but these were quickly eroded by subsequent developments, such as the raid on Pathankot in India, allegedly by perpetrators from Pakistan and mutual accusations of support to terrorists. Only Bangladesh-India relations remained warm, indeed gathered momentum with the Land Boundary Agreement, though the unresolved issue of the distribution of Teesta river waters continue to be a thorn on the side.

Socially, sharp divisions, particularly religious and sectarian divides, mark between and within the South Asian states. Hindus and Muslims; Shias and Sunnis; Christians and others; Buddhists and Muslims; atheists and believers into the otherwise syncretic Sufism; and various castes and sub-castes among Hindus; continue to remain at loggerheads with one another on certain issues. Significantly, and external linkages play a role here. Within the Muslims of South Asia, the extreme Salafi-Wahabi values of the Islamist Caliphate, from the Middle East, is making inroads into the otherwise Sufi-oriented South Asia, using methods such as ‘franchising’. In the South Asian ethos it gives a fillip to the more austere Deobandi School as opposed to the more tolerant Barehlvi views. It is significantly destabilizing because philosophically and ideologically the notion of the global Ummah (‘Muslim nation’) challenges the notion of the Westphalian concept of the nation-state, which is the norm in South Asia.

Despite a vigorously watchful media, judiciary, as well as the governance system, there has been a perceived rise of fundamentalist versions of Hindutva (‘Hinduness’) in parts of India. This, together with the burgeoning influence of the ‘saffronised god-men’ are threatening to prove unhelpful. This is also true of the unsettling behaviour patterns of radical Buddhist monks in and around the Rakhine state in Myanmar, often, as has been alleged, with the support of the local authorities. The resultant effect has been massive Rohingya migrations, not just to Bangladesh but also to Southeast Asian countries. This is both disturbing and dangerous as these migrants provide fertile grounds for recruitment by extremist organisations.

Strategically, of concern to the region and the world beyond, are the rapidly growing nuclear arsenals, as well as tactical weapons armouries, without sufficient confidence-building measures (CBMs). Although it is true that a number of security measures have been undertaken to prevent theft, smuggling or accidental discharge, such as the separation of casing from the fissile material, introduction of ‘permissive action links’ (PALs) and dispersal; the overall deterrence reflects an ‘ugly stability’ without the kind of ‘détente’ that marked the relationship between superpowers during the Cold War. This also enhances the risks of the ‘Thucydides Syndrome’, when conflicts arise out of distorted perceptions. The Greek historian had famously stated that “when Athens grew strong, there was great fear in Sparta.”

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has been notoriously underperforming. It is of course unrealistic to expect it to rise above the low state of political relations. At the same time, the SAARC Charter itself, Article X (2) for instance, prevents discussions on any contentious issues; thus structurally impeding any substantive deliberations. Moreover, all decisions made must be reached by consensus, which in essence rules out any agreement on ‘forward movement’ on most major issues. Unsurprisingly, the SAARC Preferential Trade Agreement (SAPTA), which lacked a Dispute Settlement Mechanism, turned out to be one of the least ambitious trading arrangements in the world.

No Lack of Clout

Although the South Asian entity lacks coherence, this does not mean that it lacks importance, or clout. While the idea that the region’s countries could supplant China, the Asian Tigers or Japan, as the hub of global economic dynamism is still farfetched, some South Asian countries are displaying remarkable advancement on several aspects. First, economic and political. India is already the fastest growing large economy in the world, expanding anywhere between 7% and 7.5% as of now. The Modi Government might not have pulled off all the reforms it desired, including in the Goods and Services Tax (GST), but it appears to be heading in the right direction. Its sustainable democracy, evidenced in the latest series of State Elections in West Bengal, Assam, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala, in particular, reflect its enduring pluralism, gaining the confidence of foreign investors. In Pakistan, the government, with the Army’s help, has made some praiseworthy forward movement in countering terrorism through the implementation of the National Action Plan. Also, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a part of China’s wider ‘Road-Belt’ Project, has inspired a burst of enthusiasm in the country and raised prospects of prosperity. Bangladesh, despite the series of targeted killings by extremists, appears to have achieved a culture of democratic pluralism. Bangladesh’s GDP growth remains constant at 6% to 6.5%. Sri Lanka has ended its civil war and is now focussed on development and macroeconomic management, following a peaceful transfer of power.

Secondly, the demographic dividend of almost all South Asian countries has given them an advantage over many large economies, including the European Union, China and Japan. The youth are leading the march to modernity, taking advantage of new technologies. Of course, it is a double-edged sword and could pose problems unless managed appropriately. Thirdly, the huge and successful diaspora of South Asia contain vast and positive potentials for the region and the world. They are one of the most affluent communities in the world. The Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS) in Singapore holds a Diaspora Convention every two years to deliberate on how these potentials can be tapped. The third such Convention is due on the 18 and 19 of July this year.

Finally, being the seat of ancient civilisations, South Asia boasts of an immense quantum of non-technological or intellectual resources. South Asians have proved themselves to be global thought leaders even in contemporary times. Ideas like micro-credit and non-formal education have emanated from this region, and much of the world today is marching to tunes first piped in South Asia.

Innovation in industry is still lacking on the whole, and the challenge for South Asian leaders and the region’s vibrant civil society is to foster and channel such capabilities in that direction. Thus, South Asia may lack coherence, but not clout. Its regionalisation is weak, but it is not weak as a region.

External Actors’ Involvement

The region is also where some major external powers are locked in a competition. This not just in Afghanistan, where the old ‘great game’, once played out between British India, Russia and to an extent Germany, is being resurrected in a new form, with new actors like the United States, China, Iran and Pakistan, but also in the subcontinental heartland. China has made strategic inroads into Pakistan, through the CPEC in particular, and a strengthened political alliance in general. The US has been wooing India, which has not given in, seeking to maintain its own manoeuvrability.

At the same time, the South Asian states are also keeping a wary eye on Sino-American relations. They realise that the bilateral relations between the two are the major priority for both, and assess that the worst scenario for them would be the emergence of some kind of ‘G2’ whereby China and the US would divide up the world, and the region, into agreed spheres of influence between them.

It is not just the larger and the most powerful states, the middling powers of Iran and Saudi Arabia are also becoming deeply involved in the region. Both are fighting for influence particularly among the Muslim populations of South Asia, Iran among the Shias and Saudi Arabia among the Sunnis.

The European Union continues to remain interested in South Asia, mostly for economic reasons, though the stated reasons are often different, as with human rights in Sri Lanka. Although Europe remains a main export destination for many countries, this interest is not reciprocated, as Europe is increasingly seen in South Asia as a weakening entity, immersed in fiscal, migration and terrorism issues ̶ as only a shadow of the colonial powers its members once were. Indeed, India has displayed no great enthusiasm in signing a new trade agreement with the European Union.

Conclusion

Greater intraregional cooperation will enhance South Asia’s importance and attract greater global attention, which would contribute to its prosperity, for it is still a region that holds swathes of poverty akin to that of the poorest countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. It remains to be seen if the larger states of the region can lead the way in this, as they should, with others following, as in a ‘flying geese paradigm’, the economic model where less developed economies in a region tend to follow the models of those more affluent like birds in a triangular formation. Too tall an order? Perhaps not so. As Robert Browning, the English poet much admired in South Asia had said, man’s reach should exceed his grasp, what else are the heavens for?

About the author:

*Dr Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury is Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. He can be contacted at [email protected]. The author, not ISAS, is liable for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Source:

This article was published by ISAS as ISAS Insights Number 333 (PDF)