Stork’s Nest Trial A Diversion As New Dangers Stalk Czech Democracy – Analysis

By Tim Gosling

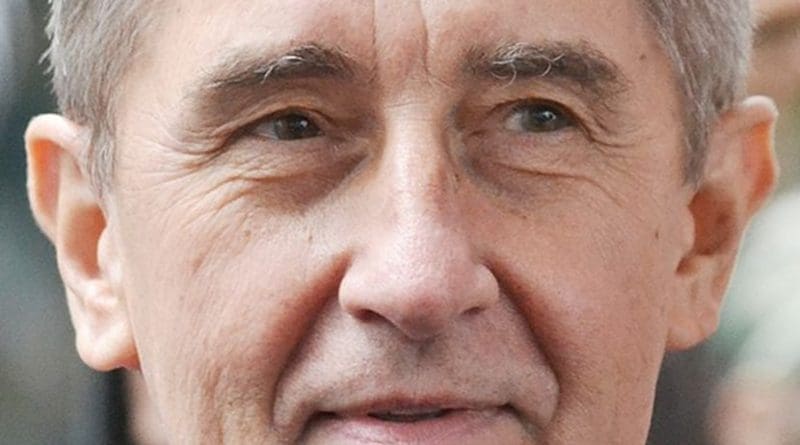

Prague’s Municipal Court began hearing the Stork’s Nest fraud case against former Czech prime minister Andrej Babis on September 12. The long-awaited trial of the populist billionaire, so recently viewed as a major danger to Czech democracy, may have some political implications, but the war in Ukraine now threatens bigger challenges.

Accusations that Babis, leader of the opposition since his ANO party was ousted in elections in October, used sleight of hand to fraudulently claim an EU subsidy have dogged him since they were made public in 2015.

The charges centre on a 50-million-koruna (2 million euros) subsidy granted in 2007 to the Capi hnizdo (Stork’s Nest) leisure resort, which sits around 50 kilometres south of Prague. Police say Babis hid that the property was owned by Agrofert, the agro-chemicals conglomerate that installed him in the upper echelons of Czechia’s rich list, in order to access the funds, for which only small companies were eligible.

But it has taken years to bring the case to trial. Three times police investigators had to recommend that Babis be charged before prosecutors finally took the plunge in March – four months after he left the prime minister’s office.

No untouchables

Despite the delay, the fact that Babis – who wields huge economic, political and media sway in the country – is due in court to face criminal charges is a victory of sorts, illustrating that the rule of law in the Czech Republic remains in good health.

“The judicial system has had to overcome many difficulties to get this case to court,” says Otto Eibl, who heads the department of political science at Brno’s Masaryk University. “It’s a sign that the law applies to all; that no one is untouchable.”

But, in similar fashion to the rest of Europe, the same cannot be said for the health of Czechia’s political culture.

Not long ago, a whiff of financial impropriety was enough to wreck political ambition, as Stanislav Gross found out when questions over his purchase of a family flat ended his premiership in 2005.

“Fifteen years ago, even just the accusation would have been the end of Babis’s political career,” Eibl suggests.

But the rise of populism has all but banished the tradition for politicians to resign in the face of scandal. It now appears a badge of honour to brazen it out, deny all, and turn the accusations on the accusers.

Babis has followed this Trump playbook to the letter. He insisted from the start that the allegations were concocted by his political enemies to halt his effort to clean up a system rife with corruption.

In this scenario, the Stork’s Nest case only strengthens his claims that Czechia’s “political elite” perverts the course of justice and democracy to serve their own ends.

The tactic worked so well that the ANO leader simply trots it out whenever he comes under pressure.

When the EU definitively declared last year that the billionaire premier had a conflict of interest regarding millions of euros in subsidies paid to Agrofert, he simply repeated the mantra.

And although much of the country refuses to swallow it, polls suggest that around 30 per cent of the electorate is convinced.

Suspicious timing

The timing of the trial is only likely to encourage the belief of ANO’s core supporters in this conspiracy.

The case opens just 11 days ahead of municipal and Senate elections that are viewed as crucial tests of support for the centre-right coalition government of Petr Fiala, Babis’s replacement in the prime minister’s chair.

ANO voters have seen it all before. Just ahead of the election in October, the release of the Pandora Papers – investigative data on offshore transactions – outlined a number of questionable real estate deals carried out by the billionaire.

Although the documents featured hundreds of names from around the globe, Babis was swift to try to link the publication of the investigation with his political rivals.

The trial will be ongoing as presidential elections run in January, a race for which Babis is a front-runner, according to polls.

“Babis will argue again that the timing is a plot to hurt his support ahead of the municipal and presidential election,” says political analyst Jiri Pehe. “But it won’t really hurt him unless there’s a conviction. That would be a very different story from the accusations. But it’s a complex case so an outcome is unlikely for months.”

Although he’s yet to declare whether he will run for the presidency, the billionaire has been raising his profile throughout the summer as he drives around the country in a camper van, a tour bearing all the hallmarks of an election campaign. It has kept him on the front pages, as his mainly elderly and poorer supporters have clashed with protestors seeking to drown him out with whistles.

Havel’s footsteps

Having been stripped of his parliamentary immunity to prosecution so he can face trial, winning a five-year term amid the comforts of the Presidential Office in Prague Castle would banish a potential (although highly unlikely) 10-year jail term in case of a conviction.

Although constitutional lawyers admit that there is ambiguity, they suggest that neither criminal charges, nor even a conviction, should block Babis from running to become head of state. After all, Vaclav Havel, who served two terms, had a long prison record thanks to his dissident days under the communist regime.

But analysts say that, despite the ongoing “non-campaign” in his camper van, the trial has delayed an announcement that he will run, and could yet help deter him completely.

“He wants to see how it will affect public opinion,” asserts Pehe. “If the effect is strongly negative, then he may decide against entering the race.”

Eibl suggests the billionaire may already have a back-up plan in place. With polls suggesting Babis would struggle to beat General Petr Pavel, the liberal former army general who officially launched his campaign on September 6, the billionaire is unlikely to put himself on the line, the analyst says. Rather, one of his trusted lieutenants – say, former industry minister Karel Havlicek or former finance minister Alena Schillerova – could be pushed into the fray in his stead.

Fog of war

The wild card, however, is the war in Ukraine.

Babis has been seeking since the Russian invasion to use the Czech government’s support for Ukraine as a stick with which to beat his opponents. Czechs are getting short-changed, he claims, while refugees and Kyiv’s military are given huge handouts.

This story has struggled to gain traction amid strong support among the public for Ukraine, but the growing impact of surging inflation and energy bills look to be changing the agenda. The centre-right government is struggling to respond to the very real fears of the country’s most vulnerable that they’ll struggle to stay warm over the winter, and pressure is growing.

Illustrating a wave of anger that surprised most, an estimated 70,000 protestors gathered in Prague on September 4, and the leaders of the demonstrations, a motley collection of pro-Russian extremists, say more are planned.

Babis will hope that this could help him boost support. The governing parties, meanwhile, will be tempted to grab at any potential prop. And driven as they were to victory by their promise to oust Babis, the Stork’s Nest trial will be hugely tempting for them.

However, although officials are braced for a rush for the public seats in the Municipal Court’s room 101, Babis’s corruption issues no longer offer the kind of impact that brought over a quarter of a million out onto the streets of Prague three years ago to demand his head.

“The governing parties will be keen to remind people of how evil Babis is,” suggests Eibl. “But they need to move on. They need to move forward and deal with the anger and fear rising around the country.”

Unless the political mainstream can step up to deal with the fears of vulnerable Czechs, a million of whom voted in October for extremist and fringe parties that did not cross the threshold to enter parliament, there is mounting worry that the upcoming elections could spring some nasty surprises.