ASEAN Is In Danger Of Becoming Irrelevant In Regional Security – Analysis

One of the issues US Secretary of State Tony Blinken is facing is US support—or lack thereof– for ASEAN centrality in regional security. Indeed, with the burgeoning US-China struggle for regional dominance, the question for ASEAN centrality is “To be or not to be”. ASEAN centrality—if it ever existed—is already under tremendous stress and its consensus-driven and non-confrontational culture limit its agency. Moreover, there is a wide variation among its members as to how important –or realistic—centrality is—particularly given the increased US and Chinese pressure on members to choose between them. Indeed, ASEAN is in danger of becoming irrelevant in management of regional security issues.

ASEAN ‘centrality’ in the maintenance of security in the face of great power struggles in its region has always been aspirational. In fact it was the US-Soviet struggle for regional dominance that gave rise to ASEAN as an attempt to ward off the negative effects on the region of such big power struggles. But its failures to manage intraregional conflict during the Cold War as well as dangerous situations in Cambodia, and now Myanmar and the South China Sea have demonstrated its ineffectiveness-some say irrelevance—in such matters.

Both the U.S. and China claim to support ASEAN centrality in regional security affairs. But the U.S. drove the formation of the destabilizing Quad and AUKUS in part because it perceived that ASEAN has been ineffective in dealing with regional security issues like the South China Sea dispute.

The pressure on ASEAN members to choose is eroding any chance of consensus. It is intense and getting more so by the day as China and the U.S. vie for the hearts and minds of Southeast Asia countries. Both have recently doubled down on their diplomatic offenses.

China has emphasized its strong point –trade and development– and assistance in combating COVID. In the last year, its Foreign Minister Wang Yi has visited all ten ASEAN members. On 14 November he met with ASEAN foreign ministers in Beijing and during the next weekends’ series of meetings with his counterparts he told his counterparts that they should voice their “joint opposition to acts that undermine peace, stability and prosperity”. On 22 November, China’s President Xi Jinping held a virtual summit with ASEAN’s leaders. China’s diplomatic efforts have paid off in that it has been accepted as an ASEAN comprehensive strategic partner. China’s latest gambit has been to repeat its offer to sign the Protocol to the Treaty on a Southeast Asia Nuclear-Weapons –Free Zone that the U.S. and its allies refused to sign.

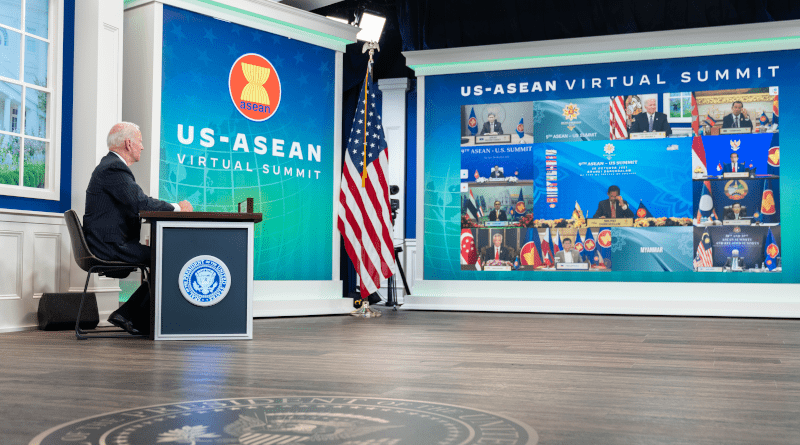

In contrast, the U.S. has emphasized security assistance and tried to persuade ASEAN members of China’s evil intentions in the South China Sea. The past six months has seen regional tours by U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, and Wendy Sherman, the Deputy Secretary of State. Last month US President Joe Biden joined the ASEAN leaders virtually at their biannual summit.

Last week on his visit to Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand, US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia and the Pacific Daniel Krittenbrink said “we need to have intense diplomacy to make sure there is not some kind of miscalculation that could lead to inadvertent conflict. In Indonesia, he said it was his first stop “in recognition of [its] leadership role” and that he wanted to “demonstrate America’s commitment to our strategic partnership with Indonesia, as well as America’s commitment to ASEAN centrality and its Outlook on the Indo-Pacific”. He was preparing the ground for US Secretary of State Tony Blinken’s visit to Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand to enhance ties. High on his agenda is “strengthening regional security infrastructure in response to PRC bullying in the South China Sea”.

But in the wake of former US President Donald Trump’s America –First policy, the U.S. has an uphill battle to win over the region. Its mantra of defending the “rules based international order” does not generate as much support from Southeast Asia’s leaders as it might think it does. Few ASEAN members see China as the primary threat nor do they see either power as ideologically or morally superior. Indeed, most Southeast Asian leaders are comfortable with different ‘orders’ for different spheres of international relations such as diplomatic, military-security and economic. Also working against the U.S. is its inconsistency. Some fear that if America’s internal politics throw up a leader from a different party, its Asia policy may change again. China while worrying is at least relatively consistent and permanent in the region.

The inevitable result of this pressure has been a split in ASEAN. The next ASEAN chair Cambodia supports its economic benefactor China and others like Laos, Myanmar and Thailand are leaning in its direction. The U. S. has a military alliance with the Philippines—although that has come under stress during Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte’s administration– and Singapore and Malaysia facilitate US military operations including its intelligence probes against China.

The next ASEAN Chair Cambodia has become a lost cause for the U.S. The U.S. has imposed sanctions and an arms embargo because of its links to China and the fear that Cambodia will allow Chinese assets to use the base. Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen has in turn ordered US weapons in the country destroyed or locked away in warehouses. More important it accuses the U.S. of interfering in its internal affairs—a cardinal sin in ASEAN-speak.

ASEAN will still play a role in the region’s security. But for it to be ‘central’ it can and must do more. It could increase the tone, tenor and volume of its ‘unified’ voice urging both China and the U.S. to show restraint. To achieve centrality in this situation, ASEAN or a core thereof must act with uncharacteristic dispatch, gusto and bluntness. It needs to find common ground and to tell both America and China what it wants them to do and not to do.

Specifically it should tell China to stop pushing the envelope and not doing so will only seriously damage relations. And it should tell the U.S. that bypassing and marginalizing ASEAN in regional security matters is not acceptable. It should also unequivocally state that it opposes the military posturing of both in the South China Sea, and — if necessary — appeal to the international community for assistance in restraining the two. It should also make clear that it will not allow itself to be used as an instrument by either side.

Perhaps it could encourage China’s rival claimants to form an ASEAN committee to deal with China. It has also been suggested that the majority exclude Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar from decisions on the South China Sea.

Whatever it does ASEAN needs to change its ‘culture’ or the situation will worsen and spiral beyond its control. If it or a core do not assert themselves, the security situation in the region will be up to China and the United States—not it. That would not only mean the demise of ASEAN centrality in regional security. It could even lead to the disintegration of ASEAN itself.