COVID-19 Vaccine Rollouts: Drivers And Effects On Health Outcomes – Analysis

By Pragyan Deb, Davide Furceri, Daniel Jiménez, Siddharth Kothari, Jonathan D. Ostry and Nour Tawk

Cross-country health spillovers from vaccine rollouts mean the pandemic will not be over anywhere until it is over everywhere. This column argues that the success of a country’s vaccine deployment in the first half of 2021 was driven by five primary factors: the severity of its pandemic waves in 2020, its procurement strategies, the quantity of locally produced vaccines, the quality of health infrastructure, and vaccine acceptance. Swift and broad administration of vaccines provides a significant boost to health outcomes, particularly in the midst of major outbreaks and accompanied by containment measures.

Vaccination is understood to be the way out of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic crisis it engendered (Gopinath 2020). However, access to and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines, especially in the early phase, has been heterogeneous and uneven. Countries in North America and Europe started vaccinations earlier and are further along than regions such as Africa and the Middle East. Across income groups, advanced economies have vaccinated a much larger share of their populations than emerging and developing economies, on average.

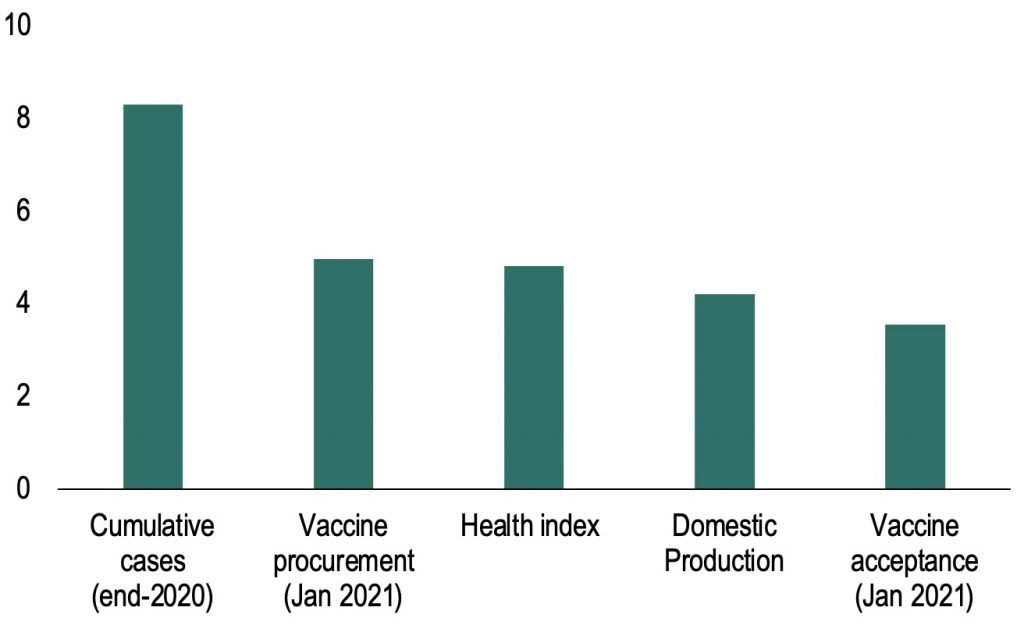

Our empirical analysis (Deb et al. 2021a) uses cross-sectional variation in vaccination rates (as of July 2021) to ascertain which demand and supply factors explain these cross-country differences in vaccine rollouts. Our results suggest that the severity of the COVID-19 waves in 2020 was the leading driver (Figure 1): countries more affected in terms of cases (for example, the US) had higher vaccination rates in the first half of 2021, potentially reflecting greater urgency to vaccinate. A population’s willingness to receive the vaccine also made a difference (Figueiredo et. al. 2020, Dewatripont 2021).

Supply-side factors such as early procurement played a critical role in explaining the pace of rollouts. The difference in procured vaccines (confirmed and potential deals) in January 2021 between countries which acted early (e.g. Israel) and those where negotiations were protracted (e.g. Germany) is associated with a four percentage-point difference in vaccination rates. Domestic production of vaccines also matters and is associated with higher and faster vaccination rates. This reflects the ability of producing countries like China to secure a larger vaccine supply and administer them more quickly. Finally, health infrastructure – hospitals, medical facilities, and doctors per capita – also contributed.

Figure 1 Determinants of vaccine rollouts

Factors affecting vaccine rollouts (impact of one standard deviation change in factor on vaccinations per 100 population)

Note: The figure reports the impact of one standard deviation change in different factors that may explain vaccine rollouts on the share of the population that is vaccinated with at least one dose. Vaccine procurement deals include confirmed and potential orders by January 2021

Vaccinations to end the health crisis

Our analysis quantifies the effects of vaccines per capita on health outcomes using real-time data for a large sample of countries. Daily data on the number of new COVID-19 infections, fatalities, and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions are used along with data on containment policies, state of the pandemic, and the dominant variant of the virus.

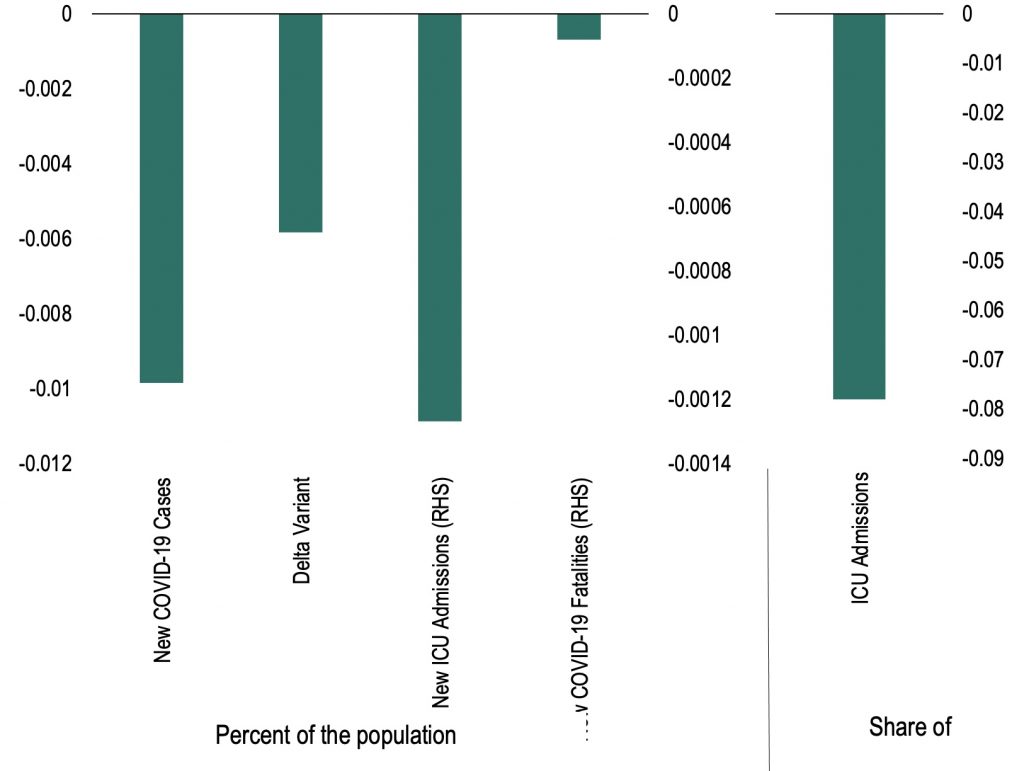

The results suggest that COVID-19 vaccines have been effective in reducing infections, fatalities, and ICU admissions, consistent with epidemiological studies (Dagan et. al. 2021, Hall et. al. 2021 among others). A ten percentage-point increase in the administration of the first vaccine dose per capita (similar to the rollout in Singapore between February and early March 2021) is associated with a reduction in daily new cases by –0.01 percentage points of the population (about half a standard deviation) after 21 days, and a decline in the reproduction rate (the number of secondary cases that would be generated by an index patient) by –0.14 percentage points (Figure 2). In addition, vaccination reduces the number of COVID-19-related ICU patients and fatalities, helping to ease strains on health infrastructure.

The health effects of vaccines increase after their administration, in line with the epidemiological literature, and the second dose contributes to further flattening the pandemic curve by reducing the virus reproduction rate. There is also evidence that the effectiveness of vaccines varies depending on the dominant COVID-19 variant: vaccines appear to retain efficacy against the highly infectious Delta variant but have a lower marginal impact compared to other strains.

Figure 2 Effect of COVID-19 vaccines on health outcomes

(percent of the population, share of COVID-19 cases)

Note: The chart shows the daily effect of a ten percentage-point increase in the administration of a first COVID-19 dose per capita on health outcomes per capita (COVID-19 cases) 21 days after administration. ‘Delta Variant’ is the impact of vaccines on new cases when the Delta variant is dominant.

Vaccine spillovers

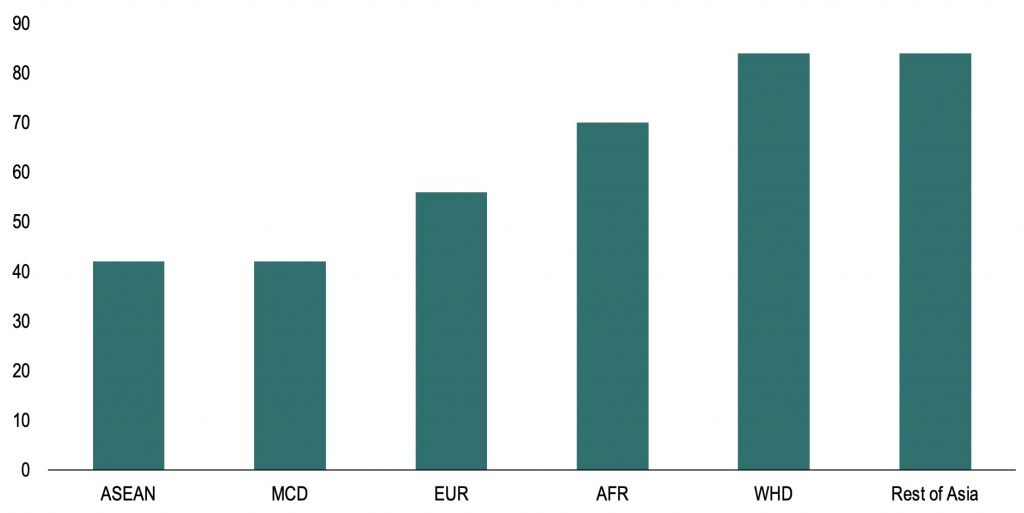

The mutation of the virus into more transmissible strains suggests that no country is safe, even those achieving high vaccination outcomes. Indeed, the rapid spread of the Delta variant from India to neighbouring countries highlights the cross-border risks from protracted waves – for instance, the Delta variant became the dominant coronavirus in ASEAN countries and in North America over a one- to three-month period after becoming the dominant variant in India (Figure 3, top panel).

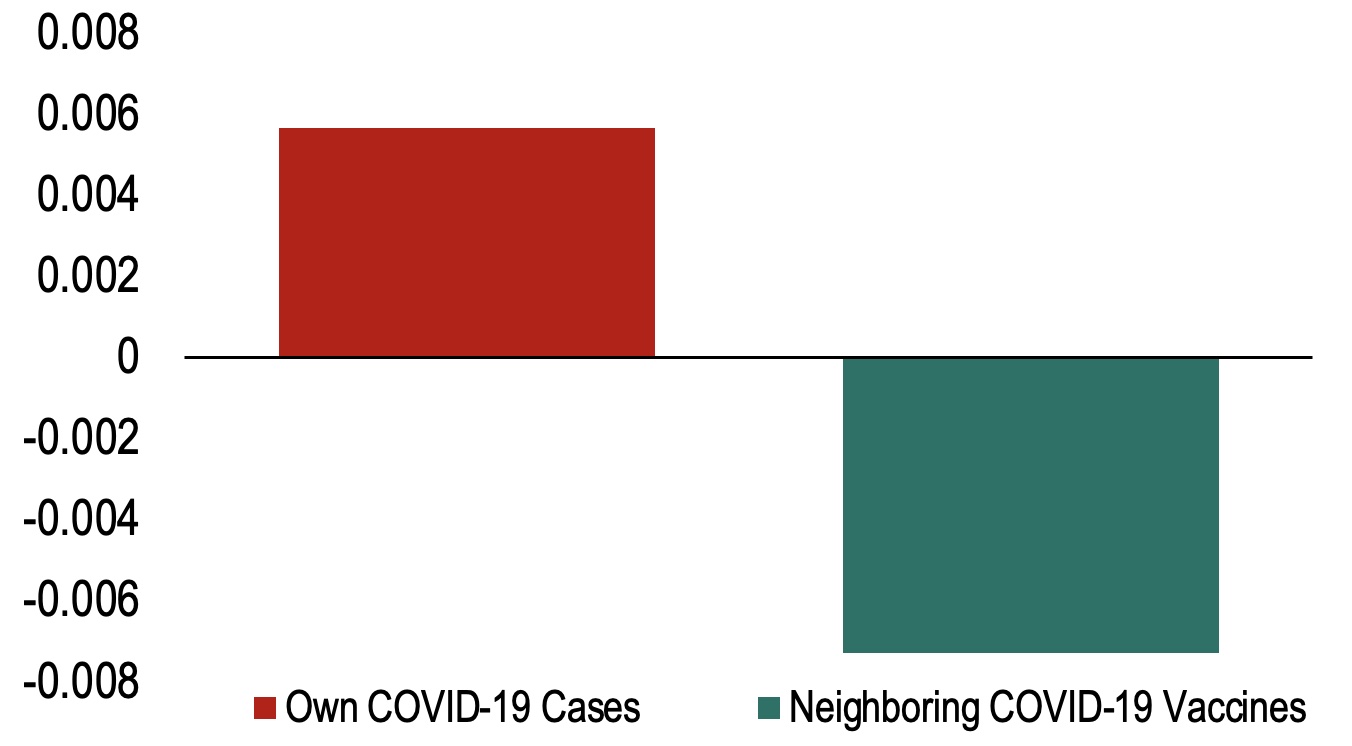

To shed light on spillovers, our empirical analysis constructs daily proxies of ‘foreign’ COVID-19 cases and vaccines in neighbouring countries, based on geographic proximity and trade linkages. The results suggest that new COVID-19 cases in neighbouring countries contribute to an increase in a country’s own infections (Figure 3, bottom panel), as movement across borders increases transmission. On the other side of the coin, there are favourable spillovers from increased vaccinations in neighbouring countries. These spillovers provide compelling evidence for international cooperation to ramp up vaccine production and ensure adequate distribution to all countries, including by sharing excess doses (Lamy 2020).

Figure 3 Spillovers from COVID-19 outbreaks

a) Days elapsed until Delta variant reached 50% of COVID-19 cases (number of days)

Note: The chart computes the number of days elapsed since Delta variant cases reached 50% of all COVID-19 cases in regions, since the date that Delta variant reached 50% of cases in India (19 April 2021). Rest of Asia includes Japan, Korea, China, Hong Kong SAR, Australia, New Zealand, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.

b) Effect of neighbouring COVID-19 cases and vaccines on a country’s health outcomes (percent of population)

Note: The red bar denotes the impact of neighbouring COVID-19 cases per capita on country’s own COVID-19 cases per capita after seven days. The green bar denotes the effect of neighbouring COVID-19 vaccines on a country’s own COVID-19 cases per capita after seven days.

Note: The views expressed in this column should not be ascribed to the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

*About the authors:

- Pragyan Deb, Economist, IMF

- Davide Furceri, Deputy Division Chief of the Regional Studies Division of the Asia and Pacific Department, IMF

- Daniel Jiménez, Research Analyst, IMF

- Siddharth Kothari, Economist, IMF

- Jonathan D. Ostry, Deputy Director, Research Department, IMF

- Nour Tawk, Economist, IMF

References

Çakmaklı, C, S Demiralp, S Kalemli-Özcan, S Yeşiltaş and M A Yıldırım (20201), “The Economic Case for Global Vaccinations: An Epidemiological Model with International Production Networks”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15710.

Dagan, N, N Barda, E Kepten, O Miron, S Perchik, M A Katz, M A Hernán, M Lipsitch, B Reis and R D Balicer (2021), “BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting”, New England Journal of Medicine 15 April.

Deb, P, D Furceri, D Jimenez, S Kothari, J Ostry and N Tawk (2021), “Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Rollouts and Their Effects on Health Outcomes”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 16681.

Dewatripont, M (2021), “Vaccination strategies in the midst of an epidemic”, CEPR Policy Insight No 110.

Figueiredo, A, C Simas, E Karafillakis, P Paterson and H J Larson (2020), “Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study”, The Lancet 396(10255): 898–908.

Gopinath, G (2020), “The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression”, IMF Blog, 14 April.

Hall, V J, S Foulkes, A Saei, N Andrews, B Oguti, A Charlett, E Wellington, J Stowe, N Gillson, A Atti and J Islam (2021), “COVID-19 vaccine coverage in health-care workers in England and effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection (SIREN): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study”, The Lancet 397(10286): 1725–35.

Lamy, P (2020), “On the production of and equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines”, VoxEU.org, 06 November.