Lessons To Learn From The Turkey-Syria Earthquakes – OpEd

The death toll from the twin earthquakes that shook a large area of southern Turkey and northern Syria on February 6, followed by many aftershocks, now exceeds 50,000 and may still rise. This makes the crisis truly one of the worst natural disasters of our times.

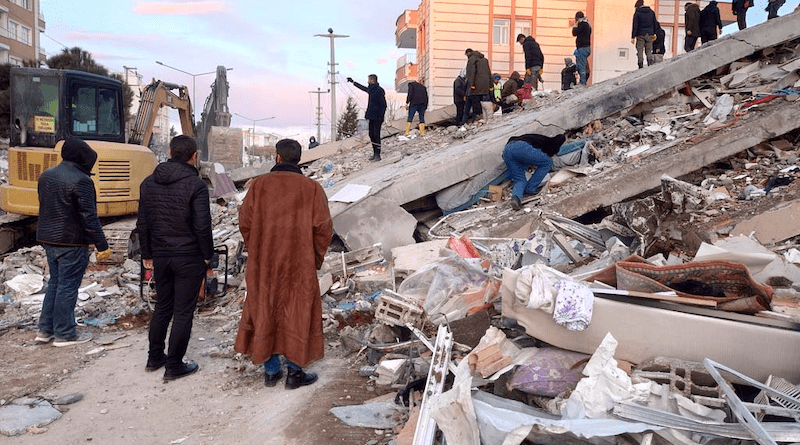

The stage in which people must be rescued from immediate danger has largely passed. Anybody still under the rubble of collapsed buildings is dead by now. But the quakes left behind a pressing humanitarian situation and a frantic response effort is still underway. Winter was in full swing when the earthquakes destroyed hundreds of thousands of homes, so survivors who became homeless found it a serious challenge to live. The advent of spring provides some relief, but the massive damage to infrastructure, the homelessness, and the war in Syria mean the situation continues to be dire.

The first month was a race against time, with people literally dying by the thousands each day. Now, it is just a matter of getting people’s lives back to normal. The current situation in that respect is much like the floods in Pakistan, 2022’s big natural disaster. But the international response to that deluge was much smaller than it is for the earthquake disaster even after passing of its most urgent stage. That is no doubt because of the high death toll in Turkey and Syria, while that reported in Pakistan is less than 2,000. But everyone should realize that once people are dead, they are dead. The whole point is to protect those still living from becoming casualties and to pull them out of their suffering. People uprooted by the floods were never in as much danger as those trapped underneath the rubble of fallen buildings, but they needed help as much as those who saw everything around them destroyed by the tremors. Many flood victims still need help. Pakistan has not recovered yet.

It may be hard for the international community to decide where they should allocate their assistance, given how weary the whole world is and the slew of crises occurring at present. The war in Ukraine is one example. Yet it is importance to ponder how the crisis in Turkey and Syria can be managed. Even though the world has extensive experience in managing countless prior disasters like this, a lot more can still be done to innovate and to find ways that people can endure humanitarian catastrophe. Everything from taking advantage of new technologies to resurrecting how human beings survived and lived for tens of thousands of years is important knowledge.

In Turkey and Syria, the challenges for both victims and responders have been immense. The first and largest tremor (7.8 on the moment magnitude scale) struck late at night. Bedtime maximized the number of collapse victims. The second big tremor (7.5), which emanated from a different fault-line nearby, struck nine hours later (the primary earthquake most likely disturbed that fault and set it loose). But its direct human toll was very low because everybody was already safely outside, though those trapped by building collapse became more vulnerable to rubble shift. Rather, structures weakened by the first quake were finished off in second quake, and of course, destruction of vital infrastructure is a big cause of human toll. But the second earthquake and the entire course of aftershocks, some of which were significant quakes on their own, made it extremely dangerous and difficult for rescue workers to do what they urgently needed to do, excavating collapsed structures and entering buildings still standing to see if there was anyone hurt inside. Help mostly had to come from far away. Many hospitals in the disaster zone were rendered unusable by the quakes and many people who would be tasked with responding to the earthquake were victims themselves, or couldn’t get access to their resources, like aid workers for Syria in Gaziantep. But damaged roads, neighborhoods turned into debris fields, and even closed airports and a fire at Turkey’s Iskendurun port, combined with bad weather conditions, created a logistical nightmare for the entire relief effort.

The situation from start consisted of countless people pinned underneath fallen structures, dying from cold, hunger, thirst, blood lost, crush injuries, etc., and countless severe and traumatic injuries which require emergency medical care. The even bigger number of people who were thrown out of homes also had to survive the freezing cold, rain, and wind. They had a whole day to find a place to sleep, at least.

Earthquakes are a disaster in which impact is determined heavily by timing, making them a game of chance. For example, Europe’s largest earthquake in the last 10,000 years (or so Portuguese scientists say), the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, struck on the morning of All Saints’ Day, when a lot of people were gathered in cathedrals that collapsed on them and candles were lit in many homes, setting off fires that would destroy what was left of Lisbon. And for each person, where they are and what they are doing at the exact moment the seismic waves strike has a big hand in their fate. That, combined with total inability to predict earthquakes more than a few seconds in advance, means that protecting humanity from this terrible natural phenomenon depends on having the right preparations in place at all times, once the seismic risk for each geographic area can be reliably determined.

The main issue is that buildings are meant to shelter people from the outside environment. But earthquakes turn buildings themselves into extremely hazardous environments, that too so quickly that people often don’t have time to safely escape from them. For lower-income countries like Turkey and Syria, buildings are not usually constructed or retrofitted to avoid crumbling in a quake, and even when they are, debris can still go tumbling. Therefore, earthquake survival mainly depends on people taking shelter within smaller hollow structures inside buildings, which is usually furniture. That is what the “drop, cover, and hold” drill is about. But there may not be sufficient furniture within quick reach, and when the whole ceiling or walls come down, even the sturdiest of beds, desks, and sofas offer little protection. In this situation, the “triangle of life” is sometimes given as an alternative instruction, in which people crouch next to large objects that could hold up large slabs of fallen walls or ceilings, creating a space next to them in which they can survive. This advice is usually refuted for well-developed countries, because smaller debris is always a huge danger, but elsewhere, it indeed is the best go at survival. The latest disaster in Turkey and Syria provides examples of that, such as one first-person account of a child surviving by crouching next to a heater, and another of a man saved by a large steel beam next to him. Remember, Doug Copp based the Triangle of Life theory upon studies of past earthquakes in Turkey.

It is not feasible to make all buildings earthquake-proof everywhere, or to do it quickly. It is easier to design the environment within buildings in such a way that people are adequately sheltered when the building crumbles. Certain rooms, like corridors, bathrooms, or bedrooms, might be built extra strong so they remain intact. The design and layout of furniture should have earthquakes in mind. In order to solve the dilemma between being protected from slabs of concrete or from chunks of concrete, triangle of life and drop, cover, and hold should be combined. That means having a large, solid object and a smaller, hollow one next to it. That will provide maximum protection from any earthquake. This “new home” for a quake victim, should they end up trapped by building collapse, needs essential amenities stocked in it, like food, water, and a whistle or fully charged cellphone. As stated, the circumstances you are in when the quake begins are what determine your chances at survival. So everyone must have situational awareness for each and every location they frequent in order to be cognizant of what preparations to put in place and what actions to take when the moment arrives.

As Turkey and Syria rebuild, they must innovate to be better protected from future quakes or other dangers like war, which also bring buildings down without warning. Destruction is an opportunity to restructure and redesign. In the meantime, survivors need to get by with what they have. For everyone, food and water are big issues, not just the lack thereof but the contamination that is quite common and spreads diseases. By and large, the earthquake victims have found shelter in some way or another. However, vulnerability to an untoward event like a powerful storm remains and since many people are crowded together into small spaces, this risks becoming a breeding ground for communicable diseases. Another problem, given the cultural setting in Turkey and Syria, is the lack of privacy, particularly when it comes to bathing.

There are many aspects to the issue of bodily care, actually. The first bath for earthquake victims is often the most important, as they need to clean off dust and dirt and they have to be checked for any injuries. Now, if a Syrian woman crawled out of a collapsed house and some random men picked her up and brought her to a makeshift shelter, will she be willing to take off her clothes so they look at, clean, and treat any cuts, scrapes, and bruises on her? Would this be done outside next to the fire they lit as their only source of light? Throughout most of humanity’s existence, women would have done this without any thought, because hunter-gatherers revolved their lives around survival and gender-based privacy didn’t become a pervasive norm until the advent of civilization. That now especially holds true for Muslim countries. One video recently making the rounds on social media shows a woman refusing to come out of excavated rubble until her rescuers give her a shawl. Honestly, they say “strong community networks” are needed to make a society resilient to disasters, but a strict adherence to gender-based privacy undermines human cohesion, and resilience, at its core.

People should also know that, when water is scarce, the best way to get cleaned with minimal water is to have someone else scrub your body and pour water. Plus, one can stand in a basin so the bathwater can be reused for washing clothes. And some might have to wait until clothes dry to get dressed again, whiling away the time wrapped in a warm shroud. Even better, a damp cloth can clean the skin with barely any water. As for privacy, a bamboo curtain or corrugated metal sheet should do. Technique really matters in survival and there are ways to handle any situation, as long as it occurs to people and as long as they are willing to do it.

Raja Shahzeb Khan is director at Pakistan’s People-Led Disaster Management (PPLDM). His academic focus is on climate change and geopolitics. He can be reached at [email protected].