Attic Discoveries: Scrapping Over Caravaggio – OpEd

“There was art before him and art after him, and they were not the same.” -— Robert Hughes on Caravaggio

The theme of rediscovery marks civilisational conversation. Lost treasures duck up and transform a period. Greek classics of medicine and philosophy, submerged by the supposed miasma of Europe’s misnamed “Dark Ages” were ultimately revived in the form of the Renaissance via Muslim votaries.

Now, Caravaggio’s work – or purported work – finds itself the subject of such rediscovery, found in April 2014 in a house on the outskirts of Toulouse. The owners would have preferred to keep the matter secret in the hope of making a sale, but a ban on its export made that academic.

Judith Beheading Holofernes, which supposedly went missing four hundred years ago, features the tried and tireless theme of Judith’s beheading of the Assyrian general, taken from the apocryphal Book of Judith, said to have been painted between 1604-5. Judith, all savage purpose, cuts deeply as blood streams forth. Her elderly maid, Abra, sporting goitres, looks on in bloody encouragement.

The last time there was this excitement about a Caravaggio attribution was in 1991, when the National Gallery of Ireland announced that The Taking of Christ (1602) was the work of the Italian master. In a dull, repetitive reflex, social media came alive with lamentation: “Dammit why is there no Caravaggio in MY attic.”

Eric Turquin, an Old Master authority, could reveal that much debate followed, despite his own belief that Caravaggio’s “tics” were all over the painting. “For two years, experts, art historians, conservators, restorers and radiologists have weighed in on the painting in the utmost secrecy.”

Nicola Spinosa, former director of the Museo di Capodimonte, was clear about this piece in the French attic: “One has to recognise the canvas in question as a true original of the Lombard master, almost certainly identifiable, even if we do not have any tangible or irrefutable proof.”

Other experts see the imitative daubs of Louis Finson, a Flemish art dealer more than mildly acquainted with the Caravaggio oeuvre. This is of little surprise to those who realise that the Italian Master became, in time, a reputational victim to imitators.

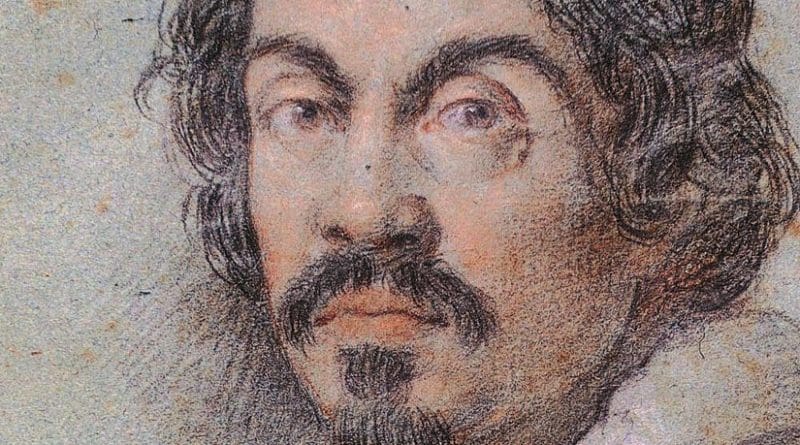

Born Michelangelo Merisi, Caravaggio was the bad boy of the canvas, a truly violent creature who mastered chiaroscuro and the depiction of life with impeccable effect. He had a tendency to draw his sword at a moment’s notice, earning a reputation as a near unhinged street fighter on arriving in Rome in 1592 at the age of 21.

He killed, and slept with blade at the ready. One recorded incident suggests he injured a waiter in April 1604 in the Moro inn with a serving dish, insulted by his manners. “It seems to me that you, poor idiot, think that you are serving a rabble!”

In his art, the transcendental seemed to be the enemy, banished in favour of brute reality, a life of sores, flesh and vulnerability. He was, as the Italian art historian Roberto Longhi noted, modern, and anti-classical, a noisy precursor.

The Counter-Reformation agenda had no place amongst these paintings, a point that troubled the Catholic Church and its social policing. As Peter Robb describes in his biographical M, the artist “lived in a time of bureaucratic power, thought police and fearful conformism, in which arselickers and timeservers flourished.” Having commissioned the Death of the Virgin for the church of Santa Maria della Scala in Rome, Church officials duly placed it under lock and key. Only a thin halo gave any clue that the subject might be divine. Her mortality was all too shocking.

Caravaggio’s violent irritability seemed to stem over to disagreement in art circles. Critics swarmed over biographical details (Caravaggio himself having left little except in police records), speculating about his tendencies with waspish enthusiasm. Bisexual suggestion, brimming homoerotic projections, tended to come to the fore. According to Robert Hughes, Caravaggio’s boys, as painted, were “overripe, peachy bits of rough trade, with yearning mouths and hair like black ice cream.”

The scrap over a grand painting’s provenance tends to leave experts open to receiving a good deal of egg on faces and reputation. Such assessments become particularly discredited before revelations of fraud and copy – the expert, as ever, remains a false witness to history, and ever open to revision.

The Lombard master has certainly not made things easy. Caravaggio dark and disputed in a history cranky with his exploits; Caravaggio contested and fought over and found, deservingly it would seem, in a place of darkness made light. Caravaggio’s work suspended in the world of inconclusive proof and notions of provenance.

Not even the export ban on the painting, which ostensibly permits the experts a good thirty months to get their eyes watery and their minds confused, will necessary cure this painting of its contrived mystery. Even the French culture ministry has decided to describe it as “a very important Caravaggian marker”. Others only see the vulgarity of money: a painting valued at 120 million euros. The painting’s notoriety is guaranteed.