Maoism: Why A Bloody Rural Revolutionary Movement Still Matters – Review

By UCA News

By Anders Corr *

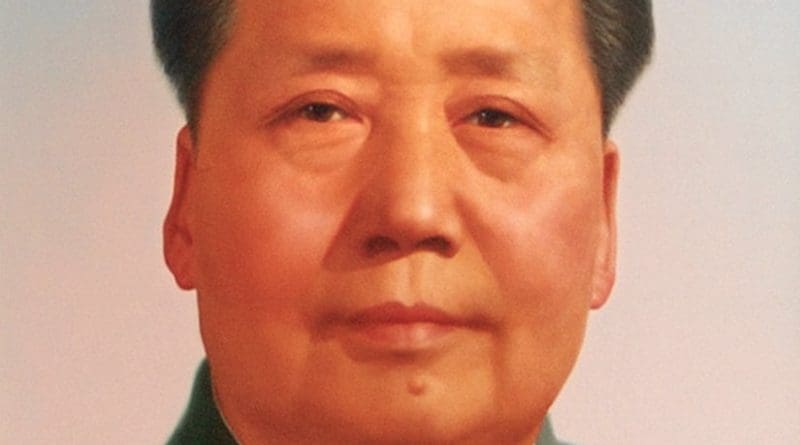

Maoism is the world’s most infamous and impactful ideology of violent rural revolution. Boosted by the strategy and goals of Maoism, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) swept to power between its founding in 1921 and its declaration of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Mao subsequently exported his highly contagious ism of violence and revolution to countries like Malaya, Vietnam, Cambodia, India, Peru, and Nepal from the 1950s to his death in 1976.

Maoism is an ideology of violence in service of equality. But its near-religious promises of a perfect society, so eagerly imbibed by its adherents, only made them drunk with the power they used to flood traditional societal structures with the blood of landlords, medium-sized peasants, and anyone, including from their own Maoist ranks, who failed to bow low enough before their new god, Mao Zedong.

Now President Xi Jinping has revived the cult of Mao in his own image. He threatens to bring this totalitarian ideology back to his own people in China, and to the world, through his unprecedented, other than by Mao himself, adoption of not only the title, but the functions of “the great helmsman.”

Like Mao, he uses totalitarian powers to squelch dissent at home, seek allies abroad and promote world revolution, this time through financial means and military power projection capabilities, rather than through the weaker means of subversion. When a Mao-like figure adopts not only an ideology that exalts violence, but an economy to support global financial influence and a technologically-sophisticated nuclear-armed military to deliver that violence globally, these are dangerous times indeed.

Julia Lovell’s latest in an impressive series of books is titled Maoism: A Global History. She expertly covers this broad story with empathy, aplomb and wit, delving into choice details, bringing life, personality and a human touch that simultaneously reveal the righteous anger of peasants to greedy landlords, and the cascading mountain of injustices that resulted, over a century of rebellion, in millions of corpses piled around the globe.

Maoism is a tragic philosophy of liberation that enslaved and killed instead of delivering people from oppression because of its strategically faulty means of subaltern (underclass) violence. By definition, the subaltern have less access to violence than their oppressors, and so utilization of the tactic is typically bound to fail.

Where subaltern violence “succeeds” in a revolution, as in China, it simply transfers the right of exploitation from one set of oppressors to another. In place of China’s old landlord class and rural aristocracy, China’s peasantry now groans under the oppression of China’s new Mandarins, the CCP from Beijing.

The old peasantry has been converted into an urban underclass that has fewer rights than its pre-communist ancestors, if one considers rights like diversity and individual liberty to outweigh in importance the materialist “rights” to own an air conditioner and smartphone, through which, not coincidentally, one is monitoried.

Lovell brings this broad swath of Chinese and global history into stark relief. But like a fly on a Dutch master painting, there are “faults” to be found in the book, fully intended by the author for those readers who appreciate such material.

The author can occasionally be uncharitable towards the human subjects she interviews, e.g., noting the dust on a revered Mao relic, owned by “one of Nepal’s staunchest remnant Maoists.” She salts her character sketches of historical Maoist leaders with their womanizing and failed love lives, an unapologetically saline window into the predominantly male world of Maoism.

The abstractions of the story are rightly held up as insights, but the author derides the simplifications of those with whom she disagrees. Every thinker and practitioner must simplify reality to get from point A to point B. Simplification is not in and of itself an epistemological crime.

What I liked most about the book was its otherwise non-ideological viewpoint. The author depicts the excess of not only the Maoists but also the anti-communists who oppose them with propaganda and unnecessary violence of their own.

A devil’s cornucopia of detail spills forth, like the use of human flesh by Maoists in India to paint propaganda in blood on village walls in India, three million Bangladeshi deaths and approximately 300,000 rapes by Pakistani forces, supported by both the U.S. and communist China in the war of 1971. There are mountains of skulls produced by millions of dead from Maoist excesses in Cambodia, including the overnight eviction of an entire city to send urbanites back to the land in Maoist fashion to learn from the peasantry. Lovell provides these distasteful yet necessary anecdotes to help the reader understand the tragedy of Maoism as an idea that sliced and shot its way through a hundred years to arrive at the present.

Lovell’s book is a must-read for anyone interested in the history of ideas, in the history of communist influence, and as a cautionary tale of the profoundly negative second and third-order effects of social movement use of violence. The book will wake us up and stiffen our spines against Xi Jinping’s revival of Maoism.

It will elucidate the sometimes righteous bases of Maoism in poverty, abuse and inequality, and as sadly blood-soaked pages that one hopes can forever be turned aside, and from which should spring a new and very different form of liberation that reaches not for the power of the gun but grows from the very human qualities of peace, compromise and kindness.

Maoism: A Global History, by Julia Lovell (London, Penguin, 2019, 606 pages, US$17.60 paperback, ISBN: 1847922503)

*Anders Corr holds a Ph.D. in government from Harvard University and has worked for U.S. military intelligence as a civilian, including on China and Central Asia.