Trump’s Seoul Speech: All The Right Points, Still No Way Forward – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein*

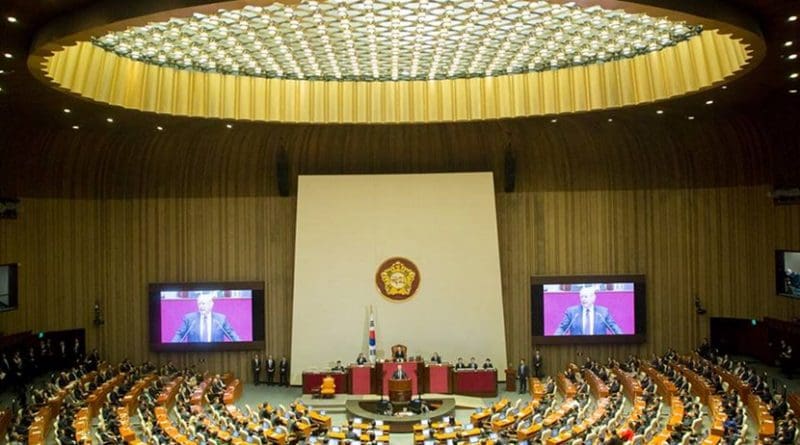

President Trump’s speech in South Korea’s National Assembly on Wednesday, November 8, 2017 was likely the best foreign policy speech he has ever given. And that is not only because expectations were low. It would be more accurate, perhaps, to say that fears were high. After months of unpredictable diplomacy-by-Twitter—calling Kim Jong-un names, making seemingly off-the-cuff-threats, undermining diplomatic efforts by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson—many feared that Trump’s speech would be yet another moment of this sort.

But rhetorical strength is no replacement for policy. Even though Trump’s speech largely checked all the necessary boxes for what a U.S. president should say during a state visit in South Korea, a fundamental divide remains between him and South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in over how to deal with North Korea, and whether military strikes should really be on the table. Trump expressed a will to talk, but also continued to push North Korean denuclearization as a precondition for improved relations. North Korea has repeated time and time again that its nuclear weapons are non-negotiable. President Moon, on the other hand, has expressed several times a will to engage with North Korea despite (or perhaps because) of its nuclear progress. This is a policy difference about as big as they get and though symbolically important, Trump’s speech did little to change matters.

First, let us look at some of the good parts of the speech, of which there were many. Some have criticized Trump’s speech for being akin to a Wikipedia page on South Korean history. Such criticisms miss the genre, context, and point of speeches such as this one. Trump did not go to Seoul to lay out new, ground-breaking policy lines. This state visit was highly symbolic, especially after all the ups and downs of U.S.-Korea relations over the past few months. By speaking on South Korea’s history, and the history of U.S.-Korean relations, Trump tried, and succeeded, in affirming American respect and recognition of both.

By anchoring the U.S.-Korea alliance in the Korean War (1950–1953), the speech signaled that the countries’ relationship is about more than strategy and geopolitics. Take, for example, the following lines, almost right at the beginning (my emphasis):

“Almost 67 years ago, in the spring of 1951, they recaptured what remained of this city, where we are gathered so proudly today. It was the second time in a year that our combined forces took on steep casualties to retake this capital from the Communists. Over the next weeks and months, the men soldiered through steep mountains and bloody, bloody battles. Driven back at times, they willed their way north to form the line that today divides the oppressed and the free. And there, American and South Korean troops have remained together holding that line for nearly seven decades.”

In other words, the alliance is steeped in shared sacrifices on the battlefield. South Korea’s war—for the Korean War was never formally ended, fighting only stopped following an armistice—remains America’s, too.

Trump also dedicated significant time to extolling South Korea’s economic and political development. This part of his speech served an important purpose: it gave recognition to a national narrative of modern South Korea that is an important source of pride for many. This narrative obscures a great deal of suffering and oppression at the hands of the country’s military dictators, but you can’t demand full and perfect academic nuance from a presidential speech during a foreign visit. The success story, next to the failed, oppressive and poor hermit kingdom, is a powerful story.

But Trump repeated the same policy the U.S. has held onto for decades, and in very clear terms. Complete and verifiable denuclearization is the beginning of better relations, and not even a guarantee (my emphasis):

“And to those nations that choose to ignore this threat—or worse still, to enable it—the weight of this crisis is on your conscience. I also have come here to this peninsula to deliver a message directly to the leader of the North Korean dictatorship. The weapons you are acquiring are not making you safer. They are putting your regime in grave danger. Every step you take down this dark path increases the peril you face. North Korea is not the paradise your grandfather envisioned. It is a hell that no person deserves. Yet despite every crime you have committed against God and man, you are ready to offer—and we will do that—we will offer a path to a much better future. It begins with an end to the aggression of your regime, a stop to your development of ballistic missiles, and complete, verifiable, and total denuclearization.”

The leadership in Pyongyang sees things differently, to put it mildly. They see the nuclear weapons as the reason they haven’t met the same destiny as leaders like Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi. Moreover, while Trump’s “message directly to the leader of the North Korean dictatorship” was at least in part meant to reassure South Korea that the U.S. stands behind it, South Koreans know full well that they, and not the U.S. president or population, are the ones in greatest risk should tensions escalate into armed clashes or nuclear war. This difference underlies the basic but crucial tension between the U.S. and South Korean administrations, where there has been little visible coordination of statements and measures during the last months’ tensions around North Korea’s nuclear program.

Of course, there is probably more flexibility in reality than can be gleaned from major speeches. Secretary of State Tillerson, when talking to reporters in Vietnam on Friday, seemed to imply that the U.S. is open to talks with relatively few preconditions. He would look for a “relative period of quiet and an indication from Kim Jong Un himself that they would like to have some type of a meeting,” reported Bloomberg. Trump’s emphasis on the U.S. being open to talking to North Korea, under the right conditions, was also a change of nuance, if not of words, from his usual tone against the North Korean regime. Perhaps more is going on under the surface. But as of now, the deadlock remains.

About the author:

*Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein is an Associate Scholar with FPRI, focusing primarily on the Korean Peninsula and East Asian region. He is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Pennsylvania, where he researches the history of surveillance and social control in North Korea, and a co-editor of North Korean Economy Watch. He publishes regularly on Korean affairs in publications such as IHS Jane’s Intelligence Review and The Diplomat, and has previously worked as a journalist, and has been a special advisor to the Swedish Minister for International Development Cooperation.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI.