Strategic Autonomy And European Defence – Analysis

The most oft-repeated objective of the re-launching of European defence is to achieve strategic autonomy for the EU. Despite its frequent invocation, the concept of strategic autonomy has different meanings and purposes.

By Félix Arteaga*

Strategic autonomy is an old goal of European defence. In general, the concept refers to the indispensable military capabilities necessary to allow a strategic actor to engage in autonomous action. In specific terms, the concept comprises political, operational and industrial components. These can be combined in different proportions, generating in turn different interpretations of strategic autonomy. This analysis presents the dominant interpretations in the EU and reviews their past evolution and current state, as well as the expectations of, and controversies stemming from, the development of EU strategic autonomy.

Analysis

The concept of strategic autonomy has different meanings, depending on which of its three dimensions –political (strategy), operational (capabilities) or industrial (equipment)– is emphasised over the others. The relative mix of these elements has varied over the course of the history of European defence construction, depending on the circumstances. After the Saint Malo declaration, and under French-British sponsorship, the European Council of June 1999 in Cologne introduced the concept of ‘autonomy of action’ to allow EU action in international crises whether operating independently, if NATO should decide not to intervene, or where NATO as a whole is not engaged (the Berlin Accord Plus in 2003 facilitated such cooperation). Following the Franco-British principles to neither duplicate NATO efforts nor create a European army, initially the objective of ‘autonomy of action’ meant force objectives of 50,000 to 60,000 troops capable deploying within 60 days and for up to 12 months (Headline Goal 2003). The autonomy of action provided by this EU rapid reaction force was mainly focused on the operational aspects of the EU autonomy of action.

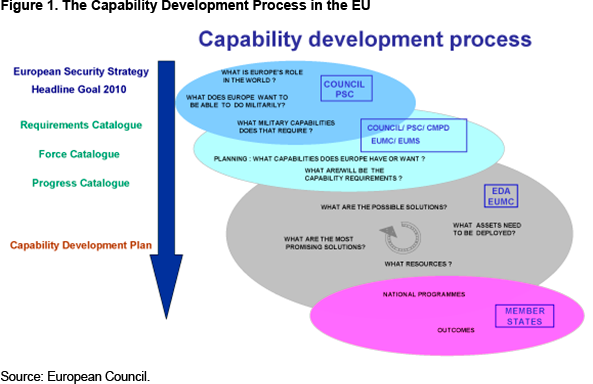

The European Security Strategy, approved in 2003, made no mention of the concept of strategic autonomy, limiting the global action of the EU to support multilateral security frameworks. The force goals of 2003 were replaced with other more realistic objectives (Headline Goal 2010) and a Capability Development Process was introduced (see Figure 1). The planning process –delegated by the Member States to the European Defence Agency– follows a sequence which moves from a delineation of strategic needs (level of ambition) to determine the operational needs (capabilities) that are later translated into industrial decisions (capacities). The logic of the sequence points to the importance of establishing solid strategic premises from the beginning; otherwise, the concept of strategic autonomy is reduced to its operational dimension and becomes little more than a military equipment catalogue.1

As the European Security Strategy of 2003 lost its relevance with time, European strategic autonomy began to be driven more by its industrial and technological component. In 2011, as the defence industry suffered a crisis without precedent due to the impact of the economic recession on defence budgets, the Commission decided to pursue more strategic autonomy for the EU. In addition to being able to act without depending on the capabilities of third parties (operational sovereignty), the Commission’s concept of autonomy had an industrial focus that included access to essential technologies and security of supply (technological sovereignty). Facing the risk of losing technological capabilities and installed industrial capacity, the Commission opted to save the ‘European Defence Technological and Industrial Base’ (EDTIB) by liberalising the market, eliminating offsets and restricting government-to-government sales. In exchange for opening up access to common funds for defence, the Commission offered even to purchase, procure and maintain military equipment.

This logic, expressed in the Commission’s July 24, 2013 Communication, changed the necessary balance between the three dimensions of the concept, as industrial interests, the market and equipment became more central than strategy. But a ‘capabilities-driven’ strategic autonomy would lead to the procurement of equipment before knowing how and for what it would be employed. This would muddle the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). To avoid such an imbalance, the Member States, in the European Council of December 2013, ruled out the idea of allowing the Commission to play the leading procurement role, but the Council recognised the importance of the defence industrial base (EDTIB) for increasing the strategic autonomy of the EU.2 Without an updated strategic orientation, however, strategic autonomy continued to develop on its industrial dimension until the European Council, in July 2015, tasked the High Representative with overhauling European Strategy.

The new Global Strategy for the Foreign and Security Policy of the Union submitted to the European Council in June 2016 did not contain an explicit definition of strategic autonomy. It did reiterate the importance of the industrial component for the strategic autonomy and defence policy of the EU,3 and proposed developing a specific defence strategy that would determine the level of ambition, the tasks, and the capabilities requirements and priorities of the Member States. However, the defence strategy was never finally prepared, and in November 2016 the Council instead adopted as its priority ambition to intervene in external conflicts to manage crises, strengthen the capacities of vulnerable countries and protect the population. Such levels of ambition limit the strategic autonomy of the CSDP by excluding collective defence from its purview.4 Consistent with such levels of political ambition, the EU could act together with third parties, when possible (preferably with NATO, building upon the EU-NATO Warsaw Agreement of June 2016) or unilaterally, when and where necessary.

At the same time, and in coordination with the implementation process for the Global Strategy, the Commission has continued to adopt measures to develop the industrial and technological base of EU defence. In its White Paper on Defence of 7 June 2017 (Reflection Paper on the Future of European Defence), the Commission extended its industrial focus of autonomy to include other aspects associated with quantity and quality of defence spending, critical technologies and the regulation of strategic investments by foreigners.

The concept of strategic autonomy among the Member States of the EU

Only a few of the larger countries have their own criteria for strategic autonomy that can be applied to the EU.5 France sees both national and European strategic autonomy as mutually reinforcing in the sense that they augment its possibilities for action; it is therefore interested in developing European strategic autonomy as much as possible. France’s concept of strategic autonomy is defined in its 2013 White Book on National Defence and Security, which aspires to see France capable of influencing events without depending on the means of others, lending it independence of evaluation, decision-making and freedom of action. This sense of autonomy is more deeply rooted in France than in other European countries because, as a nuclear power, France needs a wide scope for freedom of action; it also has a highly developed industrial and technological base controlled by the public sector (technological sovereignty).

Germany has not defined its own concept of strategic autonomy, although some documents –such as the Defence Industry Strategy of 2015 and the White Book on Security Policy of 2016– identify some of its basic elements. In the industrial realm, Germany’s objective is to preserve its critical national technologies and to expand them through relevant European cooperation.

Italy shares with Germany the lack of formal definition and the primacy of industrial over strategic interests, as established in Law 56/2012 (controlling industrial sector investment) and in the White Book of 2015. The law also distinguishes between sovereign technological capabilities –national and collaborative– which correspond to the two levels of national and European autonomy in Italy’s official doctrine.

Spain’s concept of strategic autonomy was outlined by the Council of Ministers on 29 May 2015, and associated strategic autonomy with possession of capabilities to attend to the national interests, as defined in the National Security Strategy of 2013. Such capabilities should provide the armed forces with operational advantage and freedom of action in its independent and multinational interventions. In recent documents –as in the Spanish contribution to the Commission Document of June 2017– Spain supported a notion of strategic autonomy with a more ambitious political dimension which would allow the EU to ‘influence’ in the course of affairs in serious conflicts, like that of Syria, but it also supports the primacy of security over industrial interests: the European defence industry should emerge at the end of the process of constructing true European defence, ‘not at the beginning of the story’.6

From among these national conceptions can be discerned a focus on complementarity which consists of preserving freedom of action while engaging in the protection of strategic, operational and industrial interests, complementing national with European autonomy. These countries see it as necessary to augment the strategic autonomy of the EU because it complements (although it does not substitute for) their own national capabilities, and they understand that it can be development through European cooperative efforts. They do not view it as a zero-sum gas in which any progress towards European strategic autonomy reduces national strategic autonomy (which can be guaranteed only by national mandates). A complementarity focus is clear in the document which these four countries, leading the push for ‘Permanent Structured Cooperation’ (or PESCO) in defence, directed to the other Member States with proposed criteria for PESCO to reinforce the strategic autonomy of both ‘Europeans and of the EU’.7

The complementarity focus requires additional national effort –not less– if the desire is to increase the final value of strategic autonomy. Without it, neither the integration of national capabilities within the CSDP nor priority investment in cooperation will add any value to European strategic autonomy –beyond its nominal ‘europeanisation’–. This focus is also found within the Commission’s research programmes and funds, as they seek to stimulate –not to demobilise or replace– the budgetary and industrial contributions of individual Member States.

Due to the same complementarity focus, each Member State will attempt to make European strategic autonomy to favour their own strategic, operational and industrial priorities, depending on their geography and industrial capacities, and on the existence (or not) of shared threats. Although all Member States share the need to strengthen the strategic autonomy of the EU, the specific development of capabilities and equipment will be conditioned by these differences in national characteristics and priorities, thereby testing the system of annual coordination of national planning (ie, the Common Annual Review of Defence, or CARD) to be implemented within the PESCO.

The pre-requisites of strategic autonomy

Independently of definitions and interpretations, the concrete viability of strategic autonomy depends on certain pre-requisites. At the political level, the essential pre-requisite is that such autonomy be underpinned by a coherent strategic culture. It does no good to claim a high level of political ambition if ultimately there is insufficient will to execute it. The EU now has certain capabilities –such as its battlegroups– which could act autonomously, but they have not been used due to various political, financial and operational motives of the Member States. The same could be said of Member-State capabilities which have not been placed at the disposal of the CSDP’s military missions during the processes of force generation. Strategic cultures shift with each change in government, coalition or electoral process, placing at risk the realisation of strategic autonomy. Even the Franco-German impulse behind the progress of the EU strategic autonomy could be in danger if the strategic culture of the coming Jamaica coalition in Berlin diverges over defence expenditure or combat missions. Still, the likely approval of ‘permanent structured cooperation’ will facilitate the decision-making process for acting autonomously –one of the priority objectives of such cooperation– and increase the number of CSDP military operations, if and when these missions do not awake the ghosts of different national strategic cultures (reticence or inclination to use force, social or parliamentary opposition or budgetary difficulties, among others).

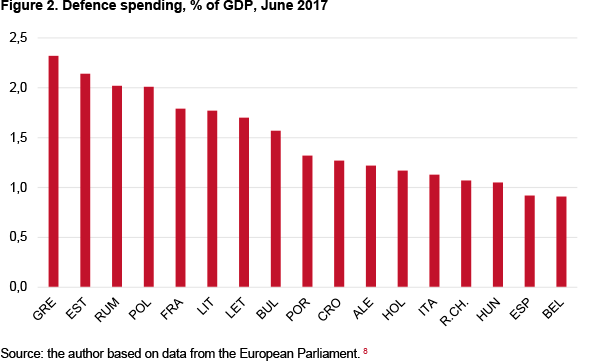

The second conditioning factor is budgetary. As already mentioned, strategic autonomy requires additional budgetary effort. This new money must come from national budgets and common EU funds. In contrast to NATO, which requires its Member States to achieve a common spending level of 2% of GDP in 2024, the EU does not set the same goal for its members. To the present, the new money contributed by those countries involved in the NATO spending commitment has been rather modest. Measured as a percentage of GDP, the countries of the EU saw an average increase of 0.09% from 2014 to 2016, while according to NATO data only Greece, Estonia, Rumania and Poland reach the 2% target, while Spain (0.92%), Belgium (0.91%) and Luxembourg (0.44%) occupy much lower places on the overall list, as shown in Figure 2.

This budgetary effort as measured in percentage terms is not very significant because the largest percentage increases come from countries like the Baltic states, whose real budgets are very small. As a result, their spending increments do not contribute much value-added to strategic autonomy. On the other hand, the countries with the larger defence budgets, or where GDP is growing, as in Spain, face difficulties to increase their larger budgets in real terms. For instance, Germany should add €24.99 billion to its defence budget of €39.51 billion in 2017 to reach the target of 2% of GDP this year. Italy would need to add €15.98 billion to its current €20.79 billion, the Netherlands €6.2 billion to its current €8.69 billion and Spain €10.74 billion to its current budget of €12.49 billion.

For a large number of EU Member States it is difficult to reconcile budget austerity and the eurozone deficit limits with a significant increase in their defence budgets. This is particularly true of France and Spain, which have Commission proceedings against them for excessive deficits. The French case demonstrates the difficulty of increasing defence spending even when there is a real political will to do so. President Emmanuel Macron wanted to increase the defence budget from 1.77% of GDP in 2017 to 2% in 2025. For 2018, an increase of €1.5 billion was expected in order to fulfil his campaign promise. But the need to contain the deficit (€50 billion) to comply with the European deficit limit instead forced Macron to reduce the defence budget by €900 million. To justify higher defence spending as a priority, Member States will compete to obtain higher industrial and technological returns in order to compensate for their contribution to strategic autonomy. On the contrary, if the distribution of costs and benefits is not balanced, it will be difficult to avoid the increasing dissatisfaction of the net contributors.

For its part, the Commission has broken the EU taboo on the use of common funds for defence, and it is proposing to increase the use of such funds for operations and capabilities research and development. The European budget will now cover the deployment of battlegroups, in addition to the common costs of CSDP operations, although the principal cost of military operations (approximately 80% of expenditure) will continue to be covered by the participating Member States. The European Defence Fund will contribute new money for research (€90 million) and development (€500 million) until 2020. From then on, the financial proposals of the Commission will depend on the budget available within the Pluriannual Financial Framework 2021-25, including the co-financing of up to 30% of the capabilities required for strategic autonomy, some €1.5 billion of the €5 billion annually that the Member-States will have to complement (for each euro contributed by the Commission, the Member States will have to contribute three or four). Nevertheless, it cannot be foreseen how much money the Commission will have available to stimulate strategic autonomy because the budget will decline with the exit of the UK (by some €10 billion) and the percentage that is devoted to defence will have to compete with other budget items, putting the community executive in the same spending dilemmas as national executives during times of austerity.

Conclusion

The definition of European strategic autonomy requires a re-definition of the concept of each Member State’s national sovereignty. As Member States lose military capacity for guaranteeing their own individual sovereignty, they should determine which national defence tasks can be ‘europeanised’, their desired degree of subordination to common planning, the individual capabilities that they will renounce and the level of specialisation they will pursue. These are decisions that are irreversible because the capabilities and areas of sovereignty which they abandon cannot be regained in a context of limited resources. The contribution to EU strategic autonomy compensates for the loss of sovereignty only if and for as long as the Member States continue to maintain the last word on the use of force. On the other hand, such a contribution will aggravate the loss of sovereignty and autonomy of the Member States if they lose control over the collective decision-making process, especially if the large countries end up imposing their decision-making autonomy on the others.

Strategic autonomy has a focus on complementarity, which requires an additional effort. The countries which are not disposed to –or simply cannot– realise this strategic, operation and industrial effort, will only be able to contribute to European strategic autonomy to the detriment of their own, contributing national resources to collective programmes without any returns to national autonomy. Since the commitments taken on by the Member States of the PESCO will be binding, each will need to carefully calculate if they have the necessary resources, or not, to support national missions as well as those undertaken in the name of EU strategic autonomy.

At the time of this writing, it appears that PESCO will be launched by unanimous decision with a sufficient majority of Member-States to participate in it. This will strengthen EU strategic autonomy, but the real boost in its political (strategic), operational (capabilities) and industrial (equipment) dimensions will depend on the level of commitment and follow-through required by the PESCO governance model which is finally approved by the participating Member States.

About the author:

*Félix Arteaga, Senior Analyst for Security and Defence, Elcano Royal Institute | @rielcano

Source:

This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute. The original version in Spanish: La autonomía estratégica y la defensa europea

Notes:

1 As of July 2008, the required capabilities included network operations, anti-landmine measures, integrated crisis management, cultural knowledge, ISTAR (intelligence, surveillance, target, acquisition and reconnaissance) architecture, medical assistance, CBRN (chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear) defence, logistical aid to third parties, or measures against improvised explosive devices or against portable anti-air missile systems, among many others.

2 In December 2013 the European Council adopted, as ‘capabilities’, remotely-piloted aircraft systems (RPAS), aerial re-fuelling systems, government satellite communications and cybersecurity (EUCO 217/30 of 20/XII/2013).

3 ‘A sustainable, innovative and competitive European defence industry is essential for Europe’s strategic autonomy and for a credible CSDP’.

4 The Strategic Concept of the Atlantic Alliance, approved in 2010, considers collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security to constitute the basic functions of NATO.

5 Armaments Industry European Research Group (2016), ‘Appropriate Level of Strategic Autonomy Report’, September.

6 ‘European Defence: A Spanish Input to Commission Debate’, June 2017.

7 The proposal of France, Germany, Italy and Spain –‘Proposals on the necessary commitments and elements for an inclusive and ambitious PESCO’, of July 2017– was supported by Belgium, the Czech Republic, Finland and the Netherlands.

8 European Parliament (2017), ‘La Coopération Structurée Permanente: Perspectives nationales et d’etat d’avancement’, July, p. 23.