The Incredible Key & Peele – OpEd

By Prakash Kona

If brevity is the soul of humor, then, Key and Peele embody the soul of the humor in an unforgettable way through their sketches that often are short enough to go through in the middle of a difficult assignment and long enough to make you feel that you watched something interesting. It has the same pleasuring effect of having a cup of tea to interrupt the routine of a regular day. The skits do an extraordinary job as stress busters. Of course they are addictive too. You watch them and then you watch them and then you watch them again.

The “substitute teacher” skits with Mr. Garvey, who earlier taught at a school from the inner city, is simply one of its kind; more so, because it contrasts the backgrounds of the teacher and the white students in the classroom. While much has been said about the performance of the teacher as a nutjob, something needs to be said for the actors who gave a convincing and representative portrait of white students in a classroom. I don’t agree with the fashionable reading that this skit reflects disparities between inner city schools where poor black kids go, and suburban schools, which have a greater number of white kids. It would only mean that black teachers and students from the inner city schools are normally aggressive and hostile. Or that black kids cannot be passive and receptive in the same sense that we see with the white kids in the classroom.

The teacher is clearly a misfit in any school on this planet. In fact, the exaggerated portrait of the black teacher from the inner city school who pronounces names the way they are written, is mocking the stereotype that inner city teachers cannot even pronounce names correctly. The hyperbole is reminding the viewer that the inner city school teacher is not afraid to be him or herself even in a classroom of white kids. If s/he does not find respect, s/he is going to demand it and make sure s/he gets it too. And, of course, Mr. Garvey does that, successfully.

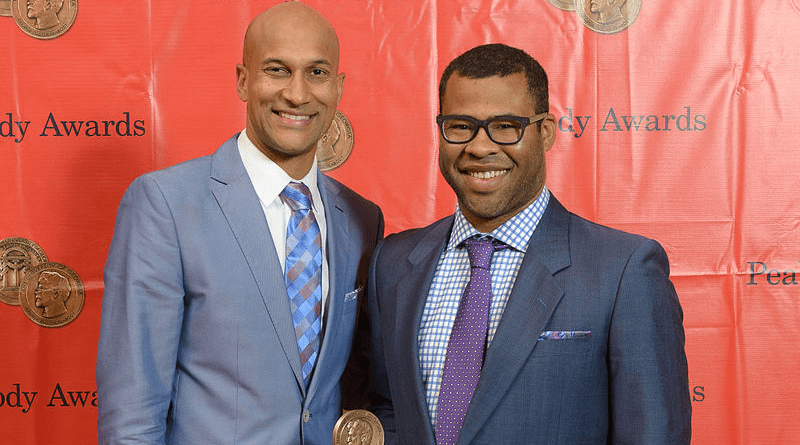

Americans are obsessed with race in the same way that Indians are obsessed with caste and religion. That unfortunately comes in the way of talent being wedded to opportunity, rather than privilege. Incidentally, both the actors Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Haworth Peele are children of white mothers, while their fathers happen to be black. However, despite the fact that in the Key & Peele sketch comedy series they are self-identified as blacks, rather than as from a mixed background, it needs to be noted that they are half-white or not completely black.

I am personally opposed to the idea that everything can be reduced to politics, whether of race, religion, region, caste or language. It is important to recognize the autonomy of performance.

When the popular Telugu actor of yesteryears SV Ranga Rao (1918-1974) died of a heart attack, his death was mourned by South Indian masses from the 1950s and 60s who grew up watching his films. Apparently in his last film SV Ranga Rao played the role of the demon king Kamsa who is determined to kill the infant god Krishna. Strangely, when the evil Kamsa was killed on screen by the god Krishna, the audience were in tears remembering that their favorite star was no more. Such was his screen presence that even while playing an evil character, SV Ranga Rao could move his audience through the power of his acting skills. This digression is important because we have to realize that performance is an end in itself.

Performance borrows elements from reality, but it cannot be mistaken for reality. Reality is the sworn enemy of performance; reality is nature, performance is people; reality is the world you are born into, performance is who you become through a reinvention of yourself; reality is truth while performance is fiction; reality is the death that is inevitable whereas performance is the “brief candle” called life – “and never the twain shall meet.” I forgot to add: reality is the black holes of the cosmos while performance is the inner eye with which we imagine deep space and wonder if there must be life elsewhere.

The genius in the comedy of Key and Peele is that they are performers who understand the dialectics of performance. It doesn’t mean that being a racial minority does not make a difference. Perhaps, it does. Perhaps, it doesn’t. Method acting insists on performance being methodical where the performer internalizes a role. While that element is clearly present in the Key & Peele sketches, a little bit of defamiliarizing too is simultaneously happening: the actors bear in mind that they are performers playing a role.

I particularly want to mention the Karim and Jahar skits, depicting two lecherous Middle Eastern guys. This sketch to me is pretty familiar because it reflects how men act in sexually repressed societies owing to a lethal combination of male bonding, sexism and homophobia. South Asian men indulge in this kind of lechery normally. However, there is a certain ease with which the roles are performed even while they appear exaggerated. I literally died at the point when Karim makes a revelation at the end of the skit, after checking out the barely visible parts of the covered women on the street such as the “bridge on the nose” and “ankle cleavage”: “Jahar, can I tell you something in confidence, right now? I am a virgin.”

Of course the whole thing is a stereotype. However, the way the performance happens, as viewers, we are aware that this is only a stereotype. That is the beauty of the performance; it is tinged with irony; irony is the essence of all performance, especially comedy. That however is not the case with the English actor, Sacha Baron Cohen. Ali G, Borat Sagdiyev and Admiral General Aladeen are funny in a way that an outsider likes to mock people of another culture, without really understanding them, leaving no space for irony in the form of self-reflection. Sacha Baron Cohen is Jewish, no doubt about that. But, Jews are a privileged minority, and hard as he may try to be consciously politically incorrect, the characters end up being politically correct in the way they become caricatures of what they are supposed to represent. That I do not think is the case with Key and Peele. The irony is much more pronounced, for instance, when they play Black Republicans, who, almost by default seem to have white wives.

Creative performers have an anti-authoritarian streak in them; I get that part. I don’t like it when they become representatives of a conventional agenda. Political correctness, whether on the left or the right, is both mainstream and majoritarian. It need not always be racist, or classist or casteist. But it reproduces dominant assumptions about culturally distant others. It perpetuates stereotypes which are only funny up to a point. What Key and Peele are able to do is to show that the people we make fun of are also capable of taking a joke made about them. I don’t think that Sacha Baron Cohen is able to do that.

Since sketch comedy has enormous potential for humor, Key and Peele are able to exploit it in a way that enlivens, while challenging the actors to be funny in a memorable way given the brief time for the performance. It’s hard to forget the ill-matched couple André and Meegan, the gay couple LaShawn and Samuel, the baseball player Rafi Benitez or the skit when the Al-Qaida terrorists are complaining about the TSA’s “shrewdness” in making “restrictions so you can only take a four-inch scissors” rather a five-inch one which would have served their purpose. One of my many favorites is “The Puppet Parole Officer from Hell.”

Given their incredible talent for playing diverse roles, I think that Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele should venture into playing complex roles in different genres, other than comedy, only to demonstrate that performance and performers thrive on their ability to be creative with characterization, rather than getting caught up with reality, in that mainstream fashion.