China’s Strategic Plan For Malaysia – Analysis

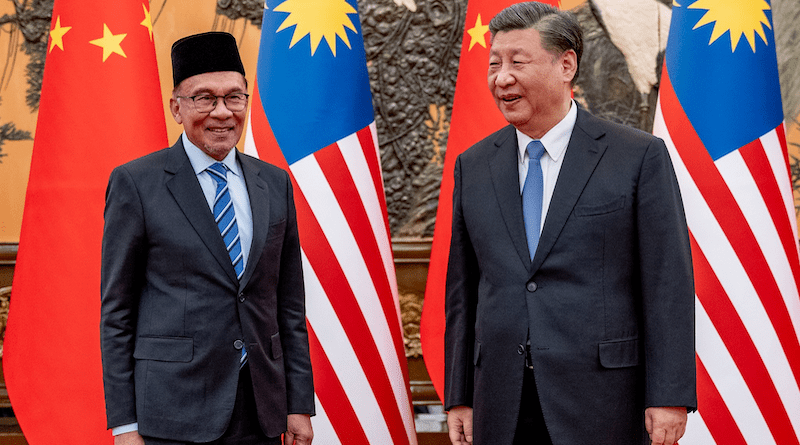

The trip to China by Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim at the end of March has secured a huge win for Beijing, which exposes the deep vulnerability and the ingrained sense of desperation on Malaysia’s part.

The prime minister is in an extremely tight spot, needing to ensure Malaysia’s concerns on Beijing’s military buildup are being channeled to President Xi Jinping while also being desperate to secure Beijing’s goodwill in economic and financial input.

Malaysia needs to stand firm on its interests, rights and sovereignty on the territorial rights and the rightful ownership of the oil and gas assets in disputed areas, and it is critical to fully utilize its cards and strategic moves in dealing with this crucial issue.

It must not squander its chips by exposing its vulnerabilities and being too eager or subservient to the dictates and moves by Beijing in framing the terms of negotiations.

It exposes the country to potential blackmailing in getting the worst outcome of having no alternative deterrence support.

Malaysia’s foreign policy under Anwar is predominantly focused on building regional cohesiveness and economic interdependence through the biggest economic power in the region, namely China.

The praise and pandering to the leadership China is an indication of Malaysia’s aligning with Beijing and while seemingly taking at face value its assurances of self-restraint.

Malaysia tried to separate the issue of the South China Sea from the overarching spectrum of comprehensive bilateral ties between Kuala Lumpur and Beijing, with the hope of this not having any bearing on the need to deepen economic ties. However, Malaysia does not share other regional players’ strategic wisdom in opening up for more US security assurances, and this is the area Beijing is exploiting the most.

Beijing uses this as a two-pronged win-win approach. First, it would potentially agree to a more accommodative stance and a toned-down approach in dealing with the dispute with Malaysia, which might mean a toned-down presence of Coast Guard vessels. This is with the hope of buying the trust and giving the goodwill in trying to secure Malaysia’s commitment and confidence in seeing China as a historically proven partner of socio-cultural and vital economic partners.

It will likely not squander too much of an opening that will threaten its SCS claims, in ensuring that Beijing’s moves in SCS will not backfire in having Malaysia to be pushed further by this fear and closer into the West’s orbit.

If that happens, it will create greater domino implications for Beijing and will give the West greater pretext and openings to coax Malaysia deeper into prioritizing and ultimately aligning with the long-term greater needs of securing its own and the region’s national survival and sovereignty as opposed to short-term economic gains.

Second, it can return to its previous escalatory intimidating and coercive tactic that is geared for pressuring Malaysia into making mistakes, and break its conventional reliance on back-door and quiet diplomacy or providing a greater opening for the West.

Beijing will then be able to use this as a pretext for a greater economic blackmailing approach. However, this remains a risky move and Beijing will likely stick to its momentum of soft power influence over Malaysia for now.

The negotiations that Beijing is pushing for must not be based on a bilateral basis, as Beijing will exercise its burgeoning leverage and cards at its disposal now, to use economic tools and other measures to dictate more favorable terms to Beijing. Beijing’s regional and global ambition with renewed narrative and soft-power messaging have been blindly followed by Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur must urgently regain its chips and cards, and to widen its playbook by pulling in greater depth of Western support and affiliation.

Official statements have reflected Malaysia’s continuous intent to look at China as the ever important economic partner, in which despite stating its autonomy and neutrality in its approach and being firm in not being cowed by external powers, it is already sleepwalking into being cowed by the mighty pressure and influence of China.

Kuala Lumpur made a strategic mistake when it affirmed that Malaysia does not see China as a competitor nor a threat, as this will in effect give more avenues for Beijing to increase its multifaceted approach in dealing with the country, where the power gap and leverage will only be exponentially increased.

Prime Minister Anwar on his address to the audience in Tsinghua University, stated that since there is no outright threat from China, Malaysia is thus happy to be a good neighbor, a friend and to benefit from China’s success. This might pave the way for a more emboldened Beijing in dictating its terms and this itself is an indication of Malaysia’s tacit alignment with future policies and agenda setting of Beijing.

The urgent economic focus seems to trump other future concerns and Malaysia remains dangerously complacent and ignorant on the threat and security setting at present.

Changing regional moves and new fears

Beijing’s broken promise of not militarizing the South China Sea is enough of an indication to send clear signals of Beijing’s all-hands-on-deck approach, where there is no permanent friend or ally in its long-term revival ambitions, having learned bitter lessons of its past.

Regardless of Malaysia’s perceived historical friendship that lasted centuries, for as long as the country can serve its geopolitical objectives, accommodative and credit support are aplenty but often disguised with ultimate future geopolitical returns.

If there is a clear indication of Malaysia’s changed stance or where the cost-benefit calculations no longer favor Beijing, the country remains vulnerable to its greater whims and fancy and increased bellicosity and other measures.

Beijing’s new countermeasures in creating fear among perceived regional players on the danger of Western interference in dictating our regional norms, in citing past danger and examples of Western imperialism and atrocities, are part of the renewed push to counter growing Western cohesion and unity in standing up for the rules-based order and international norms imposed and safeguarded by the US.

By pushing countries further under its own orbit of influence and economic order through a carrot-and-stick approach, Beijing has been gaining momentum in rebuilding its image in the Global South, playing the victim card in giving the clarion call of rising up against Western neo-imperialism and in building regional strength and identity.

Malaysia has fallen into that trap and bandwagon, whether knowingly or unknowingly. It has historically maintained its rejection of neo-imperialism and a bloc mentality and has always stood up for human rights and democracy and the ideals of a rules-based order, yet the country remains hypocritical and subdued on human-rights violations and the non-adherence to international law by Beijing.

Beijing will seek to expand its geo-strategic pursuit in the region by relying on the economic grip it still possesses over the region and on Malaysia to seek greater returns on its medium-term security and geopolitical aims.

In facing its declining momentum of economic prospects and growing pressure from the US-led embargo on key technologies, Beijing seeks to channel its resources and focus on countries where it will be easier to expand its grip, including Malaysia.