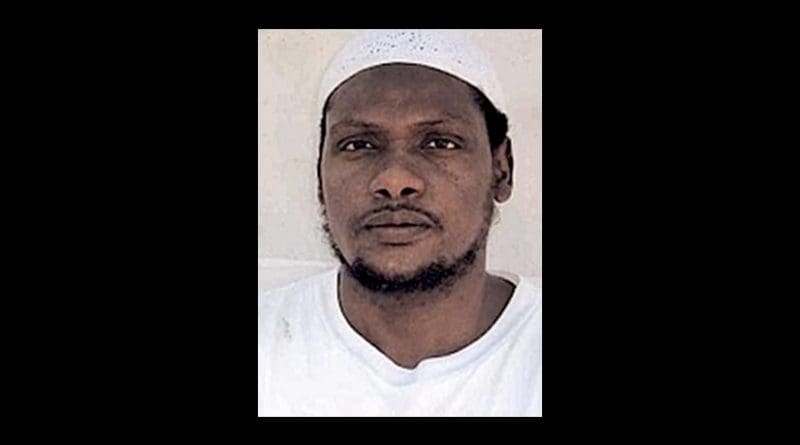

Sole Kenyan At Guantánamo, Seized in 2007, Seeks Release Via Periodic Review Board – OpEd

Last week (on May 10), the sole Kenyan held at Guantánamo, Mohammed Abdul Malik Bajabu (aka Mohammed Abdulmalik) became the 36th prisoner to have his case considered by a Periodic Review Board. A high-level review process that began in November 2013, the PRBs involve representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and, in the two and half years since they were set up, they have been reviewing the cases of two groups of men: 46 men described by the Guantánamo Review Task Force (which President Obama set up when he first took office in 2009) as “too dangerous to release,” and 18 others initially put forward for trials until the basis for prosecutions largely collapsed, in 2012 and 2013, after appeals court judges ruled that the war crimes being prosecuted had been invented by Congress.

For the 46 men described as “too dangerous to release,” the task force also acknowledged that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial, but what this means, of course, is that it is not evidence at all, but something far less trustworthy — information that was extracted from the prisoners themselves through the use of torture or other forms of abuse, or through being bribed with the promise of better living conditions.

Of the 36 cases reviewed up to and including Mohammed Abdulmalik, 21 men have so far been approved for release, and just seven have had their ongoing imprisonment recommended, a success rate of 75%, which rather demolishes the US claims about the men question being “too dangerous to release.” The eight others reviewed are awaiting decisions.

Mohammed Abdulmalik, born in 1973, was one of the last prisoners to arrive at Guantánamo, on March 23, 2007, when he was described by the Pentagon as a “dangerous terror suspect,” who had “admitted to participation in the 2002 Paradise Hotel attack in Mombasa, Kenya, in which an explosive-filled SUV was crashed into the hotel lobby, killing 13 and injuring 80,” and had also “admitted to involvement in the attempted shootdown of an Israeli Boeing 757 civilian airliner carrying 271 passengers, near Mombasa.”

However, the authorities have never given him a Combatant Status Review Tribunal (CSRT), which almost all the other prisoners have received, except for a few of the last arrivals. This means that we have never heard from him directly in the context of the administration of Guantánamo, and it also means that there does not seem to be a case against him, as a CSRT is required to be eligible for a trial by military commission.

His lawyers at Reprieve have always maintained that there is no case against him. In a profile on their website, they explained that he is a father-of-three, and that he “was transferred by his own government to [the] US secret prison system.”

As Reprieve proceeded to explain, Abdulmalik’s ordeal “began with an arrest by Kenyan police in a hotel café in Mombasa in February 2007. He was held by Kenya’s Anti-Terrorism Police Unit, during which time he was badly beaten and interrogated over alleged plans to attack a forthcoming marathon event in Mombasa.”

However, “[a]fter two weeks of detention the Kenyan authorities apparently found no evidence linking Abdulmalik to any criminal activity. But he was not set free. Instead, Kenyan authorities drove him to an airport and handed him, with no form of judicial process, to US military personnel.”

From Kenya he was flown to Djibouti, “where he was detained in a shipping container on a US military base and told by interrogators that he was about to embark on a ‘long, long journey,’” and was then flown to Afghanistan, where he was held at Bagram “in appalling conditions,” and at a second prison, and was then flown to Guantánamo.

In Kenya, Reprieve noted, there has been “justified anger amongst civil rights groups” about the government’s perceived betrayal of a Kenyan citizen, although in response, as Reprieve also noted, the Kenyan government has “tried to duck responsibility by denying that Abdulmalik is Kenyan.”

Describing this as “a laughable claim,” Reprieve explained that “[d]ozens of people, including his father and the midwife who delivered him – in Kisumu on the shores of Lake Victoria – stand witness to his Kenyan birth and heritage.”

The Kenyan government has also sought to deny its involvement in Abdulmalik’s transfer out of Kenya by US forces, by claiming that he was deported. However, the US Ambassador to Kenya, Michael Ranneberger, confirmed on Kenyan radio that Abdulmalik was “moved to Guantánamo Bay with the full consent of the Kenyan government … [as] part of collaboration between the two governments to fight global terrorism.”

Assessing his situation at Guantánamo, Reprieve noted that he was “no longer regularly interrogated,” and saw this as “perhaps a sign that the US government have realized that he is not the big fish they thought he was.”

In September 2012, the Daily Nation also covered his case, when his step-sister, Mwajuma Rajab Abdalla, said from her home in Mombasa, “We don’t know what has happened to him. We last heard from the government about him two years ago. Nobody is willing to help us.”

The 2012 article quoted extensively from Abdulmalik’s own testimony about his experiences, provided to his lawyers — how, after he was first seized, “[i]n the car, two of the policemen held pistols to each of [his] temples, and one of them choked [him] and then crushed his head under his boot. Another still held a pistol to his head. The policeman continued to choke [him] until one of his colleagues said: ‘Not so tight, we’ll kill the guy.’”

Held briefly in a variety of facilities in Kenya, “he saw three white men observing him from outside the interrogation room” in one prison — presumably, Americans — and, when taken to an airport, “saw, through the bottom of his blindfold, a huge plane with a US flag painted on its side.” Subsequently “stripped naked, put in a diaper and then dressed in a tracksuit,” he was flown to Camp Lemonier, a US military facility in Djibouti, where “he remained chained to the floor of the cargo plane, with his eyes, head and mouth covered.” In his testimony, he said that, at one point during the flight, US soldiers “took him to the door of the aircraft and threatened to throw him out.”

In Djibouti, “he was taken to a shipping container and put in an interrogation room with four people — two guards and two interrogators — who told him that he was connected to people from all over the world” involved in terrorism. It was here that he was also told that he was “suspected of planning to attack the World Cross-country Championships in Mombasa in 2007.”

He said a US interrogator told him, “You have two possible journeys: one back to your family, or another that is very, very long. If you don’t tell us what we want to hear, you will have a long, long journey; you will spend your life in a cage.”

On the flight to Afghanistan, Abdulmalik said, he felt “very alone, confused and scared,” and on arrival, at a time when Bagram was still in US hands and full of prisoners, he was “held in a wooden pen in the cage-like cells,” and was also “taken to another secret prison in Kabul, where Americans took his photographs, weighed him, and gave him a blue jumpsuit to wear.”

On arrival at Guantánamo, he said, he was held in solitary confinement for two months, and was only allowed to wear shorts. Then, as he described it, “the US government discovered that he was not the big fish that they thought he was and moved him to Camp IV … reserved for suspects the US believes present the lowest risk.”

In 2008, in a demonstration of how relentless and largely pointless intelligence-gathering was a major part of the fabric of Guantánamo and the “war on terror,” through the use of photo albums of the prisoners and of men wanted by the US, he told his lawyers, “Months ago, I asked for charges — I am not an enemy combatant! I begged for a process. They said, ‘No, no process’. Instead, they bring pictures of Somalis: you know him? You know him? You know him? Hundreds, maybe thousands of pictures. I don’t know those Somalis. But no court.”

Speaking of the CSRT that never happened, despite being promised by the Pentagon when his arrival at Guantánamo was first announced, Clara Gutteridge, then working with Reprieve, said, “There have] been no legal proceedings. If there is any evidence against him, he has said he is willing to face trial, even in Kenya, rather than be detained against his wish in Guantánamo.”

As the Kenyan newspaper then suggested, in a sharp analysis of US detention failures post-9/11, “Abdulmalik’s continued imprisonment probably highlights the extent to which the United States remains imprisoned by its past mistakes. While its approach to terrorism has evolved, the failure to charge him of any crimes shows how far Washington still has to go if it wishes to develop a rights-respecting national security policy. Guantánamo’s single most important distinguishing feature has been an indefinite military imprisonment without fair process.”

Mohammed Abdulmalik’s Periodic Review Board

In its unclassified summary prior to the PRB, the US government described Abdulmalik as having been “inspired by a radical imam to leave Kenya in 1996 to receive extremist training in Somalia, where he developed a close relationship with members of al-Qa’ida in East Africa (AQEA), to include high-level operational planners.” The government further alleged that he then “became an AQEA facilitator,” and reiterated its original claim that he “was closely involved in the preparation and execution of the November 2002 attacks in Mombasa, Kenya,” in which 13 people died. It was also reiterated that, “[i]n February 2007, Kenyan authorities arrested [Abdulmalik] for his involvement in the Mombasa attacks and transferred him to US custody a few weeks later.”

At Guantánamo, it was noted, he has been “a highly compliant detainee,” although intelligence analysts stated that, in debriefings, he “offered conflicting narratives about his activities prior to his arrest and would not provide much information of value about his AQEA associates or the group’s operations.” The summary added that, after a few months, “he expressed discomfort with providing the US with further information and became uncooperative with interrogators,” and, in mid-2010, “stopped coming to sessions altogether,” leaving gaps in the US’s knowledge of his activities from 1997-2002 and again from 2003-2006.

The authorities also noted that he “has not expressed continued support for extremist activity or anti-US sentiments, although he is critical of US foreign policy,” adding that he “considers himself a Quranic healer and holds conservative Islamic views that are likely to make transfer to and assimilation in non-Muslim countries difficult.” If transferred, the summary’s authors noted, “we expect that [he] will attempt to reunite with his wife and children who currently reside in Somalia.”

Below is the opening statement of his personal representatives (military personnel appointed to represent him in his PRB), who noted that he “has not made any negative or a derogatory remark toward U.S. policies nor has he expressed an interest in extremist activities of any kind,” and who also commended his interest in business and his previous work experience as “small business owner for a fishing and diving company,” which, they noted, “should provide him with skills and abilities to obtain employment regardless of where he is transferred.” They also noted his desire to be reunited with his family, his status as a compliant prisoner, and his role in Guantánamo as a cook for his fellow prisoners. No statement from his lawyers has been made publicly available.

An announcement of the board’s decision will probably be made within the next one to two months, and although it is, of course, impossible to know what the board members will decide, it continues to seem significant to me that he was never regarded as significant enough to be granted a Combatant Status Review Tribunal, and I would hope, therefore, that his release will be recommended.

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing

Mohammed Abdul Malik Bajabu, ISN 10025

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. We are the Personal Representatives for ISN 10025, Mr. Mohammed Abdul Malik Bajabu. We will be presenting Abdul Malik’s case this morning with the assistance of his Private Counsel.

Abdul Malik has always been willing to participate in the Periodic Review process since our first meeting in mid-March 2016. After initially explaining the reason for our meeting, he was visibly overjoyed to have this opportunity. He has remained positive at all of our meetings and has always demonstrated his gratefulness and his respect toward us.

During our meetings, Abdul Malik has conveyed his hope of reuniting with his family. Although he is willing to be transferred to any country, he would prefer a country that has a significant Arabic-speaking majority. He is also agreeable to participate in any rehabilitation or reintegration program that may be required. He longs to get on with his life after his transfer from Guantánamo Bay, and he is ready to reconnect with his wife and children. He looks forward to seeing his sisters and brothers and meeting some of the newest members of his family who were born during his time in detention. His experience as a small business owner for a fishing and diving company should provide him with skills and abilities to obtain employment regardless of where he is transferred. He has a strong mind for entrepreneurship. In fact, his thirst for business knowledge includes reading Dale Carnegie business management books.

Abdul Malik has been a compliant detainee and has gained a sense of achievement by being a camp cook for his fellow detainees. With the chance to meet and mingle with so many people of various cultural and religious backgrounds here at GTMO, Abdul Malik has also had an opportunity to be aware of and appreciate these other beliefs and customs which will serve him well to wherever he is transferred. Adbul Malik speaks and understands English very well.

We are convinced that Abdul Malik’s intention to pursue a better way of life if transferred from Guantánamo Bay is authentic and that he bears no animosity towards anyone. Of note, Abdul Malik has not made any negative or a derogatory remark toward U.S. policies nor has he expressed an interest in extremist activities of any kind.

Thank you for your time and attention, and we look forward to answering any questions you may have during this Board.