Foreign Worker Exploitation: Dark Legacy Of Malaysian History – Analysis

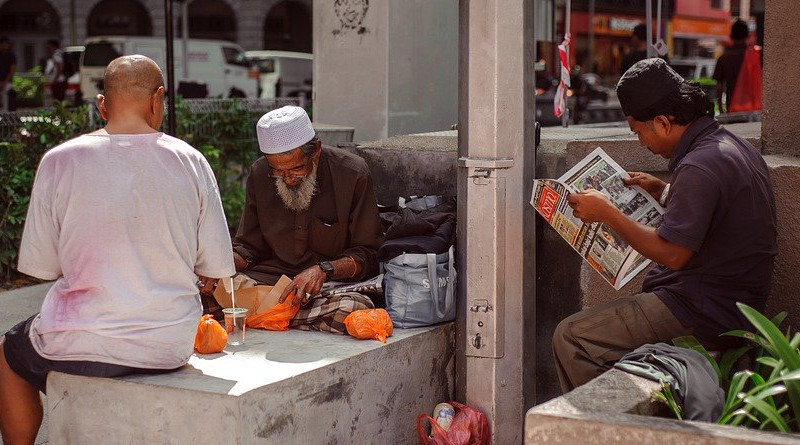

Two raids last month by Malaysian authorities who detained hundreds of foreign workers in areas around the Kuala Lumpur Wholesale Market have raised concerns from labor activists of mistreatment and a fear that such raids frighten foreign nationals into hiding among the Covid-19 crisis.

But in addition to that the raids, near Jalan Masjid India, are the latest events to raise concerns over Malaysia’s appalling treatment of foreign workers, which in many cases approximates outright slavery. Foreign maids are sexually abused and raped, workers lose limbs through unsafe equipment, workers are overworked and underpaid, refused rest days, passports confiscated upon arrival, shunned as second-class citizens, and thought of as being subhuman: that is the predicament of Malaysia’s foreign workers today.

According to unofficial estimates, up to 6 million foreign workers are in the country, amounting to 18.6 percent of the country’s 32.6 million population. This expatriate labor force is made up of 2.27 million legally working and another 2.5 to 3.37 million illegal foreign ones. Foreign workers represent somewhere between 31-40 percent of the Malaysian workforce of 15.3 million, employed primarily in what is called “3D” (dirty, dangerous, and difficult) jobs in the plantation, agriculture, construction, manufacturing, and service sectors.

Some workers are enticed to go to Malaysia and are sold by traffickers en route in Thailand. The camps and mass graves found in Wang Kelian, Perlis, back in 2015 have indicated the extent and horror of this practice. The camps were used as staging areas while smugglers waited for payments, before Rohingyas and Bangladeshis were sent to work in Malaysia and beyond. Even though a Royal Commission has been concluded, there has been silence from the government, indicating a massive and coordinated cover-up, as all evidence was quickly destroyed by the police at the scene before forensic experts could visit the site.

Some come without permits, on social visit passes to work in shops, food stalls, restaurants, entertainment outlets and massage parlors. When raided, they face fines and jail before being deported, while the employer gets away without any legal censure or penalties.

There are reports that syndicates entice young people to come to study in Malaysia, where they find that after paying sometimes in excess of RM15,000 for arrangements to study, they are forced to work as illegals as construction workers to pay concocted debts.

According to the Global Slavery Index 2018 annual report, most foreign workers are burdened with ‘debt bondage’, within the domestic, retail, construction, manufacturing, and primary sectors. Commonly, workers from Nepal and other countries have to borrow upward of US$2,000 at interest rates of 48 percent plus, taking years to pay back. Workers were reported as working 10 hours per day without overtime, being paid below the legal pay rates. Workers’ passports were held by employers and their salaries withheld during the last three months of their contract, to “settle any outstanding matters.”

It isn’t just the debt burden. Foreign workers are often forced to work in horrid, sub-standard, dangerous conditions, with temperatures soaring into the 40s C. Their living conditions are often cramped and over capacity, with employers deducting around 20 percent of wages to pay for food and accommodation. They are often not paid what was agreed in their home countries.

According to a media investigation, companies such as Samsung and Panasonic are facing allegations that they have exploited and underpaid their foreign workers. The US Government has just lifted sanctions that it imposed last year on two Malaysian glove manufacturers, WRP and Top Glove, suspected of forced labor and overtime, debt bondage, withholding wages, and holding workers’ passports.

Foreign worker plight may be increased further, according to a press statement by the anti-slavery NGO Freedom United. A government proposal is being contemplated to deduct 20 percent of workers’ salaries in a scheme to prevent them fleeing from their employers, and restrict their movement.

Foreign workers have been neglected during the Covid-19 crisis, even though their health has major implications upon general public health, as the Singapore outbreak of Covid-19 among the nations’ foreign workers showed. Flip-flops about who should be liable for Covid-19 testing, and the large number of undocumented workers who fear coming forward for testing, because of threats of detention and deportation, are exacerbating the problem.

Foreign worker recruitment, processing, and placement is a massive business, worth more than RM2 billion (US$478 million) annually to manpower and private employment agencies. The costs of the extension process, extra charges made by private employment agencies and medical screening issues often encourage foreign workers once in Malaysia to work illegally. There is a ready market in counterfeit foreign worker cards, which would save the foreign worker RM4.5-5,000 per year in charges and immigration levies. There is an underground network in manpower agencies handling illegal workers. This leaves workers vulnerable to the system and subject to exploitation by unscrupulous employers.

Although foreign workers are legally protected by Employment Act 1955, just like Malaysian workers, no government agencies check their welfare. There are also no formal legal channels for them to bring up work grievances or make complaints. Thus, workers have no way to enforce the terms of their contracts. Trade unions don’t represent them and any problems may be left to diplomats from respective embassies, usually when it’s too late.

Victim of Malaysia’s dark legacy

History is a powerful force upon how society sees itself and others in the present. Harsh attitudes towards foreign workers have their origins in the annals of Malay history. There is a long history of Malay enslavement of the indigenous people, or Orang Asli, and fellow Malays. The Orang Asli were hunted down like animals, by Malays, made slaves and often traded. According to accounts at the time from Colonial officers, Malay treatment of slaves was barbaric, where slaves were abused, neglected, caged up and chained like animals, raped, and killed at whim.

Islamic theology was circumvented by enslaving other Malays through ‘debt bondage’. This would include the wife, children, and any children born while in captivity.

Slavery was an institutionalized custom of Malay society, a pillar of social standing, politics, and a driver of the local economy. The number of slaves held signified the level of prosperity. The abundance of slaves was a source of power, and an elite class of slave-owning Malays did all their work through slave labor.

Many of the Malay customary ideas of the time still have a residual influence on contemporary thinking. As Malays wouldn’t even think of doing tasks slaves would do, today contemporary Malaysians would not consider doing jobs that foreign workers are employed to do. Malays prefer to employ people rather than do the work themselves within their own enterprises, which is one of the reasons many entrepreneurial start-ups fail.

As employers of foreign workers, Malaysians have become hard taskmasters, harsh, and unfair of their employees. There are many horror stories about the sexual abuse and rape of maids, workers’ wages being cut for inventive reasons, and downright dishonesty in which employers refuse to pay final wages before workers return home.

Little has changed

Today, the manpower business has no code of conduct, an industry that has attracted both domestic criminal elements and high-ranking government and political figures due to the lucrative profits and low risks. Many recruiting agencies are also moneylenders, pressing workers for repayments at hefty interest rates. The agencies have strong leverage over workers’ families at home if loan payments fall behind.

The brother of former deputy prime minister Zahid Hamidi was alleged to have created a manpower monopoly in which only one company could get worker approvals. Another report claimed that up to RM9,500 in bribes was necessary per worker approval. The Nepali Times last year claimed that a nexus of top Malaysian and Nepali politicians, bureaucrats, and businesspeople set up a system where all Nepali migrant workers had to take a biometric test through an approved company run by the syndicate. This report also linked Zahid, who is now facing charges, to the scam.

However with the Zahid case progressing at snail’s pace, and the recent dropping of charges, and court discharge of former prime minister Najib Razak’s stepson Riza Aziz, and withdrawal of corruption charges against former Sabah chief Minister, Musa Aman, there is strong speculation that Zahid will somehow escape conviction.

Latheefa Koya, the former Chief Commissioner of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, charged that the industry is full of corruption. Talk about moving responsibility from the Home Ministry to the Human Resources Ministry, however, will achieve nothing without a thorough policy review of labor requirements, conditions, and the costs and benefits of foreign workers. The insuring of foreign workers for employment-related injury that commenced last January 1, and talk of the Malaysian Trade Union Congress to represent foreign workers is too little, too late. Policing the industry with a code of conduct, inspecting foreign workers’ workplace conditions, putting in a grievance mechanism, and reforming the visa system should be high priorities.

What is most alarming is the stratification of 18th century society – aristocrats, commoners and debt-slaves has really changed little today. There is still a great hierarchy within the Malaysian social system that has culturally ingrained attitudes towards foreign workers. Millions of foreign workers have very few rights at all. The exploitation is sourced from a deep-seated cultural mindset, exposed through narratives and action towards foreign workers today. Until these attitudes change, foreign workers within Malaysia will continue to be harshly exploited.

Originally published in the Asia Sentinel