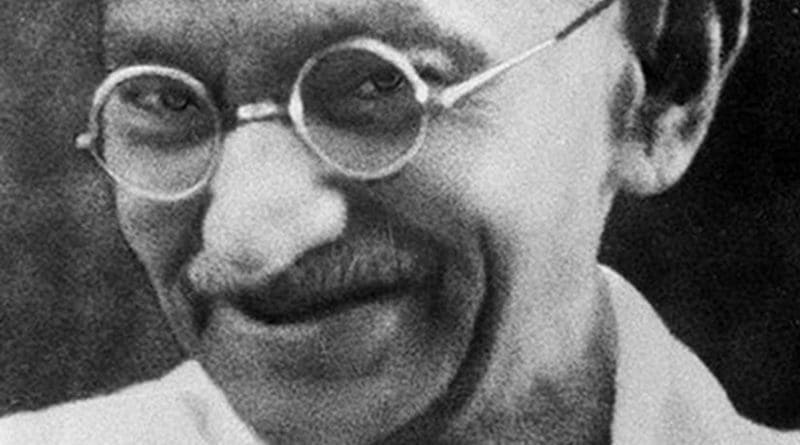

Mahtama Gandhi’s Relevance To Indian Politics – OpEd

By Prakash Kona

India needs Gandhi. South Asia needs Gandhi. Blacks in America and Europe need Gandhi as much as the whites. Kurds, Kashmiris, Sudanese, Syrians and Latinos need Gandhi. With the increase in sectarian thinking everywhere the world needs Gandhi more than ever before.

Gandhi is humanity’s present; at any point in time we need to fall back on Gandhi to resolve questions related to how we confront injustice; thus, Gandhi is both our past and our future as well.

For reasons that defy the imagination, in the past couple of decades, no effort has been spared, however small, in vilifying Gandhi in the vilest of terms possible by “intellectuals” from the Indian subcontinent, especially the ones who happen to be spokespersons of marginal communities and minorities. Among other things, this is largely owing to the singular contempt which the Dalit leader Dr. Ambedkar has had for Gandhi that is as much personal as it is political.

I never understood the logic behind the anti-Gandhi campaign conducted with a viciousness that makes you tremble. For that matter I don’t understand Dr. Ambedkar’s resentment of Gandhi, and the former’s surprisingly limited insight into the nature of colonialism whose victims are predominantly from oppressed social groups. If Dr. Ambedkar resented Gandhi’s consistent emphasis on Dalits being within the Hindu fold, what follows is clear: most Dalits are opposed to caste system but definitely not to Hinduism as a religion; they feel as much Hindu as any other follower of the religion, irrespective of the caste that they belong to.

You cannot tell a Hindu Dalit that he or she should stop being Hindu because of casteism; it’s not an argument that would appeal to a large number of them. The Hindu Dalit is able to successfully make the distinction between caste and religion. Merely because they are opposed to casteism, it does not mean that they want to stop being Hindu. This is why I see as unworkable the new alliances being forged between Dalits and Muslim minorities, which are not deep-rooted to begin with, and are the result of a politics of convenience more than anything else. A more tacit alliance that has worked better than the above one is between Christians and Muslims, perhaps because both are religious minorities, and feel so.

The rabid portrayal of Gandhi as an enemy of Dalits and minorities is unfounded and has come with a terrible price: the emergence of Hindutva as embodied in the success story of Narendra Modi who knows better than his enemies that the Indian collective unconscious is Gandhian more than anything else. It is the wily politician in Modi who figured out that appropriating Gandhi’s legacy, at least in principle, is imperative for him to gain power.

PM Modi’s Gandhian mask, the image of the father-figure, is so transparent that it would make you laugh except that its effects are so serious that you would freeze in your tracks. However, I credit Mr. Modi for realizing that playing this role of a “celibate,” other-worldly, parent-like leader with no personal interest could fetch incredible electoral results for himself and his party. But of course I am at a complete loss to see what it is about “celibate” men or women that the majority of Indians find attractive in theory, because as a culture, unlike with the Buddhists and the Catholics, celibacy does not have any place in our social and emotional history. In fact, single men and women are not even given houses for rent in most towns and cities because they don’t have a “family.” In the country where I live everyone is supposed to get married, have kids and live unhappily ever after. If Modi was an ordinary person, trust me, he would have a very hard time getting a place to rent for himself. This is the proverbial Indian double-standard for which there is no logical explanation.

I feel nothing but distaste for those traitors of the masses, India’s educated classes, who seriously need to take the lion’s share of the blame for the rise of the Hindu right in India.

This distaste applies in particular to so-called intellectuals from the left, ivory tower teachers and pea-brained student leaders from public, state-run universities, the principal opposition party and its allies and to everyone else who failed to realize that Gandhism is the only weapon (the irreversible and unfailing Brahmastra in the Mahabharata that Karna uses against the demon Ghatotkacha, thus, inadvertently, changing the outcome of the war in favor of the Pandavas) to defeat the dangerous and divisive agenda of the ruling party.

More than secularism which is seen as a “negative” term, the majority in India need a Gandhi version of Hinduism; one that believes in Ahimsa and faithfully observes the live and let live policy. Gandhism should have been the platform to confront the lies and deception being systematically propagated by the ruling party against the “secularists” (who, in my modest view, are hardly secular in their private lives), rather than using a term that doesn’t work with the public like “secularism” itself, whose meanings are as diverse as its histories.

Gandhi is the mantra against which Modi’s “charms” are bound to fail for the simple reason that Gandhi is opposed to everything that Modi and his party stand for. Gandhi identifies himself as a Hindu, is a Hindu and loves people. His idea of Hindu manhood is built around forgiveness and goodness, an idea of manhood that is the polar opposite of the Hindutva ideology.

That is the Hinduism we need to counter the propaganda of the ruling party rather than ignorantly calling the religion all sorts of names imaginable. If, for the sake of argument, I am a Hindu, even if I disliked everything that Modi and his party might be doing, simply because someone has abused my religion, I would stand with him rather than the opposition. Isolating and targeting one religion, in this case Hinduism, for crimes committed by people of all religions is unfair and unacceptable to say the least.

Why should Hindus or Hinduism be identified with a narrow, sectarian school of thought called Hindutva? No one says that every white Christian from the 19th century is a slave-owner or a colonizer! No one in his or her right mind would say that every citizen of Saudi Arabia is also a fundamentalist or that all the Jews of Israel are Zionists! The Hindus are as human as the others in both good and bad. In fact, my own view is that to a large extent “class” and “gender” defines Indian social and economic reality. It is poor Dalits and poor women who bear the brunt of the injustice along with the poor from other communities. This tendency to relegate class to a secondary status and prioritize caste does not reflect ground realities and is mostly the agenda of individuals and groups from the left, right and centre who need to keep the divisions alive because it suits their interests.

And what about the followers of the religion embraced by Dr. Ambedkar as an alternative to Hinduism! Ask the religious minorities of Myanmar and the Tamils of Sri Lanka what the majoritarian Buddhists have been doing to them! Yet, it doesn’t mean that either of them is less than human. This is simply how hegemonies operate: with a one-sided view of the world, a world in which there is no place for others. Hegemonies have to be fought and defeated bearing in mind that a new one is always sprouting round the corner.

It serves a greater purpose for Modi’s opponents to intelligently demonstrate the un-Hindu aspects of the current dispensation at the power centre. These are civilizational ways of approaching a political question. Gandhi himself could effectively demonstrate to the world that colonialism is un-Christian. Raja Ram Mohan Roy could argue that there is nothing in the Hindu scriptures that justified the evil practice of burning widows. They spoke in the language and in the contexts that the masses were familiar with. This is what needs to be done to break the hegemony of India’s economic and social elites.

The current approach by Modi’s “educated” opponents is exactly that of the 19th century upper class, upper caste intellectuals after the failed war of Independence in 1857 looking at power for solutions and answers. Instead of addressing the ones in power what Gandhi did was not to look at the British or the educated Indian elite but look in the direction of the poor and illiterate masses. Intuitively he knew that they held the keys to India’s emancipation as they still do in the year of a deadly pandemic, 2020.

If the opposition must generate the support to defeat Modi in elections, that is not possible merely by talking about “dissent, “free speech,” and “secular values,” words, whose meanings are not obvious and make no difference to the poorest of the poor who are looking for food and dignity, which come from freedom from hunger, poverty and unemployment. Morally bankrupt and socially inept, the role of the educated classes in Indian politics is essentially over as is conclusively revealed through Narendra Modi’s electoral victories; their lifestyles are anathema to the exploited poor; Modi is able to capitalize on their disenchantment by effectively showing himself as one of them, which clearly he is not.

Recognizing the humanity of your enemy and seeing him or her as a human being is a vital part of any civil resistance. This is one thing that a powerful man is always afraid of: to be seen as a human being with normal human failings. He wants to be seen as an idea or an abstraction to be loved, hated, admired or feared. By not falling into the trap of seeing any person however powerful as anything except as a normal human being, there is an essential victory that is obtained. Powerful men are just men who sometimes cannot even sleep well, thanks to the burden of living to an image of power, as Shakespeare portrays in his history plays.

No country can survive for long where the majority of its people lack conscience and dignity, two things Gandhi made central to his gospel of nonviolence. While Gandhi’s greatness is that he could make goodness a political weapon there is a point at which he completely fails.

It is not Gandhi’s political views or his complex worldview that are fundamentally problematic because, except for school text-books and the lip service paid once in a way by politicians and bureaucrats, he stopped being a serious factor in this country a long time ago. Where one has to be really careful with Gandhism and Gandhi is what he expects from people in their personal lives. Gandhi’s utopia, if you can call that, where everyone is morally upright, originates in his conviction that individuals could be perfect; he refuses to see that people are normal human beings incapable of the feats that he could perform which are close to impossible to say the least.

Though Orwell and Bertrand Russell, both could see what it is about Gandhi that is medieval and reactionary, it is to Sadat Hasan Manto, the South Asian writer who combines the insightfulness of Chekhov with the realism of Maupassant, that we owe a life-like portrayal of where Gandhian idealism fails. In one of Manto’s short stories “For Freedom,” there is a character Ghulam Ali, a naïve young man with genuine good intentions deeply in love with an intense young girl Nigar, who shares his patriotic fervor.

Both are followers of a Gandhi-like character, Babaji, who subscribes to a notion of purity, so much so that after the marriage of Ghulam Ali with Nigar is solemnized, it is proposed that both of them would lead a celibate existence despite living together until India is liberated from British rule. Babaji’s view is that, “the real happiness of marriage could only be attained when the relations between a man and a woman were not physical.” However, at the end of the story, when the narrator accidentally meets his old friend Ghulam Ali, the latter is the father of a child simply because it was impossible for the couple to physically stay apart from each other while living under the same roof.

As darkly funny as the story is, the narrator reflects on the downsides of the Gandhian kind of purity, which is unnatural and expects too much from ordinary mortals:

“I have no regard for those places where men are frogmarched along rules that run contrary to their nature. Attaining independence was, without a doubt, the right thing to do and I could understand it if a man should die in attaining it, but that some poor wretch should be defanged, made as benign as a vegetable for its sake—this was utterly beyond my comprehension.

Living in huts, forsaking bodily comforts, singing God’s praises, shouting patriotic slogans—all this was fine, but to slowly deaden one’s senses, one’s bodily desires—what was meant by that? What was left of a man in whom the longing for beauty and drama had died? What distinctiveness, what particularity could remain then between the various pastures of these ashrams, madrasas, shelters and retreats?”

In post-colonial India, Gandhism has become an excuse for some of the worst kind of emotional repression and moral self-righteousness that can be imagined. False aspirations of moral perfection “where men are frogmarched along rules that run contrary to their nature” end up creating irresolvable contradictions as can be seen in the day-to-day hypocrisy of South Asians where they say one thing and do something else. People are human, people are individuals, they need the freedom to make mistakes and grow out of them.

As attractive as is the anarchist view of human goodness, a social order will never be a moral order. We cannot trust people to be naturally good; some degree of force is inevitable for civilized existence. Unfortunately it is this kind of idealism where a person is expected to be “benign as a vegetable” that is at the heart of the catastrophic partition violence that divided India and made it two countries.

We cannot have a social order based on non-human goals such as physical or emotional purity which involves the slow deadening of the senses. Few individuals achieve such perfection and must be admired and revered for that, but an entire society cannot be made to sacrifice the emotional side of its nature. Endowed with the mind of a great writer, Manto could see where Gandhi and Gandhism were wrong. It is only keeping in mind the pitfalls of the kind of puritanism followed by Gandhi which is very close to extremism, that Gandhian politics ought to be the basis for confronting the majoritarian violence emerging from the ruling party’s interpretation of religion.