Can Nestlé Source Peruvian Palm Oil Without Deforestation? – Analysis

By SwissInfo

By Paula Dupraz-Dobias

Palm oil cultivation is booming in Peru, boosting the income of small farmers who supply Swiss food giant Nestlé with the product. But the crop is one of the main drivers of deforestation in this part of the country. Can farmers really “go green” amid so much demand?

Like nearly all landowners in this part of the northern Peruvian region of San Martin, Marilú Bustamante has been growing oil palms for more than a decade. It was the safest bet after 20 years of terrorism and violence linked to drug trafficking. Her gamble paid off, allowing her to send her children to school, purchase farming machinery as needed and create jobs for four regular employees, as well as another four part-time workers.

She sells to the local palm oil buyer, Palmas del Espino, which has granted her loans over three years when she and her husband began growing palms and continues to provide them with technical assistance. The company is part of a specialised commodity processing group called Grupo Palmas, which in turn supplies Nestlé’s Peruvian affiliates with palm oil, an ingredient found in everything from soap to pizza dough.

While Peruvian palm oil production only represents 0.4% of global output, in San Martin, the product contributes to some four percent of gross domestic product. Nestlé is one of the top buyers in the region. In Peru, the company owns several confectionary and food brands including the popular Sublime chocolate bars and Donofrio ice cream.

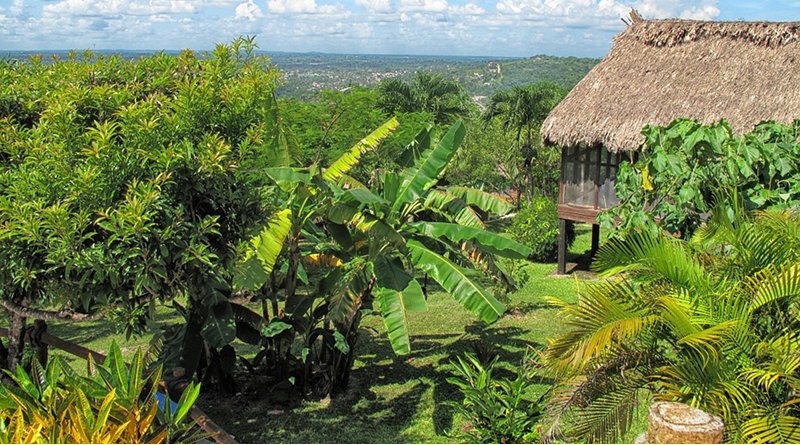

Surrounded by lush plantations that stretch as far as the eye can see, Bustamante recalls a time when her land was mostly pasture that also included Amazon rainforest. The farm is in a region called the jungle’s eyebrow, a reference to a sometimes hilly that flattens out as it descends into the Amazon basin. Her husband insisted on clearing the forest land, which once provided shade for cattle, to make room for the money-making crop.

“I would have saved a bit of the forest,” says Bustamante, who moved from the coast to the district of Uchiza in the 1980s. “We didn’t have the slightest idea of the impact we are causing with deforestation”.

Zero-deforestation commitment

Deep in debt but proud to have 30 hectares to her name, Bustamante is among the larger landowners in a growers’ association taking part in a sustainability project financed by Nestlé: Rurality. The initiative is managed by Earthworm (formerly TFT), a Switzerland-based consultancy, and aims to “increase sustainability and transparency among smallholders as well as boost productivity and income of the farmers working in the company’s palm oil supply chain”.

The Rurality project therefore supports Grupo Palmas’ training of farmers in sustainable agricultural technology– through its “Cadenas Productivas” programme – to increase productivity to avoid any further deforestation.

It came about after an article published in The Guardian in 2015 pointed at Grupo Palmas affiliate, Palmas del Espino’s plans to clear-cut some 9,300 hectares of primary forest. Nestlé then asked Earthworm to propose a code of conduct and action plan for its relationship with its Peruvian partner on the ground.

Grupo Palmas has since published a No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) declaration. While the parent company is a member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the sector’s voluntary platform for responsible production, Palmas del Espino branch is engaged in its own RSPO certification process.

Nestlé has committed to zero deforestation by its palm oil suppliers by next year. But it is unlikely to achieve that goal unless it ensures that farmers from Peru and elsewhere come on board.

A lucrative crop

Oil palms produce fruit two to three years after planting. After that they can be harvested every two weeks, depending on the size of the plantation, making the crop highly productive and lucrative.

On average, a small holder produces annually approximately 15 tonnes per hectare. At $88 paid per tonne of fruit, a farmer stands to earn $1320 gross per hectare annually.

“When I had cattle, it was costly to breed them,” says palm oil farmer Manuel Rodriguez. “When the animal is converted into money, it means that the animal is gone. With palm, we harvest, we get paid and the plant is still there.”

Rodriguez grows palm on land that was abandoned after coca, the main ingredient in cocaine, was eradicated from it. He is one of the few able to grow palm on the slopes above the wetlands thanks to a water source that runs through his property. Alternative crops, such as palm, coffee and cacao, were introduced to farmers after the eradication – a development that environmentalists blame for the rapid deforestation of Peru.

The farmer

Another way to increase production is, of course, clearing land and planting more crops. In principle, expanding the production area is not an option due to the no-deforestation commitments farmers make with companies they work with as they apply for sustainability certification. Working with suppliers that have such certification is one way companies like Nestlé try to remove deforestation from their supply chains.

In reality, swissinfo.ch observed areas of freshly cut aguaje forest (moriche palm or Mauritia flexuosa) flanking the newer palm groves near Uchiza.

“We are aware of the role of small holders in deforestation,” says Nestlé’s global responsibility chief for palm oil, Emily Kunen. “It is understandable that in search of better livelihoods if you are able to generate income by clearing forest space, that’s an obvious choice.”

Some like Fernandez complain it is a struggle to absorb additional administrative costs that come with sustainable certification, as well as higher costs to produce sustainably, including with fewer chemical fertilisers. He says that technical information – including soil studies and effective natural methods of fighting pests – is still lacking in Peru.

Fernandez is one of several palm growers to mention that people are starting to grow coca again in his region, a claim supported by a report from the United Nations drug control agency.

“Prices are down so much, it’s not enough for people to survive,” says Fernandez. “For us who are legal, we pay taxes, meaning we have costs and expenses and we don’t have much profitability”.

Through Nestlé’s partnership with Earthworm, farmers are also being encouraged to diversify their income sources to remove incentive to expand plantation surfaces and aggravate deforestation. For example, Bustamante supplements her current palm oil earnings of approximately $3,300 per month by selling guinea pigs, a staple food in the Andes. Each animal sells for $6 to $9. She estimates it will take her another 10 years to pay off a loan of $121,000 to Grupo Palmas but is proud of what she has achieved in a country were the minimum monthly salary is barely $261.

The supplier

Nestlé’s efforts to end deforestation are dependent on cooperation from the Swiss food giant’s suppliers on the ground, namely Grupo Palmas. Sandra Doig, sustainability chief at Grupo Palmas, told swissinfo.ch it is not that difficult to get authorisation for deforestation in Peru but that this is now against the ethos of the company. Doig was attending a United Nations conference in Lima organized by UNDP’s Green Commodities Programme, which had offered this journalist a fellowship to cover the event.

“You do not plant palm in forest areas,” Doig said. “Plantations have to follow certain steps. Every new activity has to be evaluated from a sustainable perspective.”

To keep tabs on whether Grupo Palmas and the farmers that it works with continues to clear forest in this part of Peru, Earthworm recently mapped the area for so-called high carbon stock (HCS) vegetation to identify natural forests and to be able to later track any alterations in the landscape.

Earthworm’s project manager, Jonathan Maerker, sees efforts towards change on the part of Grupo Palmas affecting everyone in the company “from the CEO down”.

“They still have a lot to prove and are on a journey to improve. Things don’t change from one day to another. It’s a process”.

The buyer

While Grupo Palmas supplies Nestlé with palm oil, its local subsidiary, Palmas del Espino is responsible for purchasing the raw palm plants from farmers and passing them on to the supplier, after being processed by Industrias del Espino, a sister firm. In order to get to a point of zero deforestation, Nestlé is also dependent on cooperation from the buyer.

However, it hasn’t been a smooth process. According to the Environmental Intelligence Agency (EIA), Palmas del Espino planned to clear areas in the northeastern Loreto region, home to virgin rainforests. Approval had been controversially granted on 24 December 2014 to the company for “change of use” from forest land to agricultural exploitation – a technical loophole in the law – by the regional government just days before it handed over to a new administration.

The company, which had received prior approval by regional government authorities, proved to be the first case by a palm oil company taking advantage of the relatively little attention paid by central authorities to isolated areas of the jungle.

Another case that created an uproar was the illegal clearing of 7,000 hectares of land in the Western Amazon rainforest in Peru by the affiliates of United Cacao, a Cayman-based firm that boasted RSPO certification.

Many growers here blame Grupo Melka, the local subsidiary of the United Cacao company’s abuses on negative public perceptions of the commodity.

Meanwhile, Grupo Palmas now says it is seeking to develop other uses for the land in Loreto that does not involve deforestation.

Earthworm was unable to confirm whether the freshly cleared land seen by swissinfo.ch at the edge of palm groves near Uchiza belonged to small holders or Grupo Palmas, whose local affiliate also own large plots of land in the area. In any case, Earthworm identifies them as areas where they are trying to foster forest preservation.

‘Pie in the sky’

So will Nestlé meet its goal?

Stephen Donofrio is the director of supply change initiatives at the NGO Forest Trends, which focuses on tracking sustainable development commitments by global companies. He says zero deforestation is the ideal goal for companies but “may be the pie in the sky” and “not totally possible” for all companies to achieve.

“What is important are clear policies on social development or in agricultural production, and understanding who your suppliers are to assure they are engaging in best practices,” he says.