India And Afghanistan: Recalibrating An Old Relationship – Analysis

By Chayanika Saxena*

Afghanistan’s National Security Advisor, Hanif Atmar and the Deputy Foreign Minister, Hekmat Khalil Karzai, are all set to meet their Indian counterparts over the weekend. Purportedly, the invitation to have this interaction was extended by the Indian National Security Advisor, Ajit Doval over a telephonic dialogue with Atmar almost a fortnight ago.

Coming in the backdrop of deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan and a resultant reversal of the American foreign policy towards maintaining of troops in the country, many are reading this impending India-Afghanistan interaction as a sign of change in their respective orientation towards the other. But, is it so?

India and Afghanistan have often alluded to their civilizational proximity to talk of an undying bonhomie between them. While it would be mistaken to transpose their present sovereign identities into an ancient, or even a modern past when these two entities hadn’t even existed, their closeness in the present times is too hard to ignore. At the cultural level, or what is broadly described as public diplomacy, India has certainly been given a high score by the masses of Afghanistan. Economically too, India has extended a monetary largesse to Afghanistan in the form of assistance to many vital projects, including its new Parliamentary premises and a major dam in the west of Afghanistan.

Militarily however, India has been a rather reluctant contributor to Afghanistan. Supply of military hardware has been minimal and seldom direct. While this can be attributed to a rather modest indigenous base of Military-Industrial Complex in India, a lot of it has got to do with the regional equations in South Asia which both India and Afghanistan are a part of.

Placed in between these two countries is the nuclear-power state of Pakistan, which in many ways, has been at the root of significant security predicaments encountered by those across the Durand and Radcliffe lines. Choking the supply lines of military transfers between India and Afghanistan is former’s ostensibly real apprehension of igniting an all-out ‘great-game’ that would stretch its aging equipments to an extent which will be ill-afforded at this stage.

In these circumstances, to hear of the possibility of a direct transfer of three MI-25 helicopters to Afghanistan by India is bound to appear as a shift in the latter’s dealing with the former. Here however, it becomes crucial to underline that while this potential transfer can appear as striking given that it may happen even as the state-to-state ties between India and Afghanistan are a little mellow, it is certainly not anything new. Thus, to refer to this potential supply of choppers to Afghanistan as reflective of a reversal in India’s foreign policy would not be an appropriate choice of phrase.

Notwithstanding its cultural and economic partnership with Afghanistan, India’s military dealings have been very measured and cautious from the beginning. Even when the Karzai government was incumbent in Kabul—a regime that is believed to have had a pro-India bend—India was not overly-excited to extend its military assistance to Afghanistan beyond what its own national interests could have permitted.

Besides training of Afghan military personnel at the NDA that continues till date, India’s military assistance to Afghanistan in the form of arms and ammunition can be best described as a very limited cache. These make the potential transfer of the MI-25 choppers not even a diversion in India’s approach to Afghanistan, let alone be called a reversal. Rather, the current Indian orientation is very much an extension of the country’s regular way of dealing with Afghanistan—one that can be described as ‘proceed but with caution’.

Moreover, military transfers were already envisaged under the Strategic Partnership Agreement which was signed with Afghanistan back in the year 2011 itself, making the potential supply of choppers nothing new. As per the agreement, ‘the training, equipping and capacity-building of the Afghan National Security Forces’ was expected to receive support from India, and which it has with accelerations and hiccups alike.

As for Afghanistan, it approaching India is not a strategic somersault as many would like to believe. On the one hand, where Afghanistan is doing nothing but reminding India of its old commitments, on the other hand, if there is anything striking about this move at all is that Afghanistan is evolving its foreign policy to respond to the changing circumstances. Like any other sovereign nation, Afghanistan too is making calculated moves to address its own needs- where is the U-Turn?

While the views in the Indian media are reflecting strategic pragmatism in suggesting that the country be receptive to the incoming Afghan call, they are simultaneously describing this move as a U-Turn in Afghanistan’s foreign policy vis-à-vis India. In fact, a section of the media is jubilant as it claims that Afghanistan has finally come around having recognized the ‘reality’ of Pakistan!

It is undeniable that the complications in Pakistan do not make it a partner one can trust, but this moral askance of Pakistan that is now making Afghanistan to recalibrate its policies does not amount to its ‘India waapsi’.

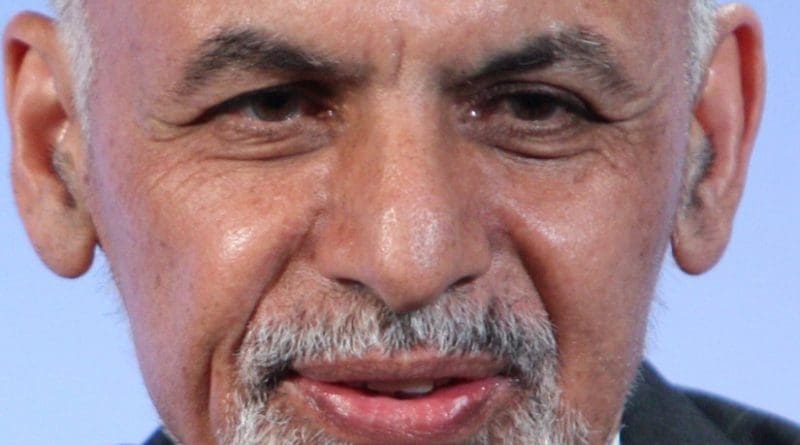

Afghanistan continues to prioritize its interactions on the basis of the ‘Five-Circle’ policy that its President, Mohammad Ashraf Ghani, has delineated at different instances since his coming into power.

A model of concentric, but hierarchical circles, the Five Circle policy of the incumbent President fashions Afghanistan’s international engagements on a scale, such that those countries that are critical to its domestic security and other sovereign interests form the inner core. India is placed in the fourth circle, or the outer core; a fact that has not gone down well with this South Asian giant.

Simultaneously, there has been an expressed elevation of Pakistan and its ‘all-weather friend’, China to positions of prominence. More than any personal preference that can be tied to the ethnic rivalry between the previous President and the current one that could have contributed to this ‘shift’ in regional alliance, the decision to keep Pakistan closer was simply informed by the idiom: keep the friends close and the enemies closer.

Holding the strings to Taliban and its affiliates, the importance of Pakistan in delivering these two constituencies at the table of talks was accurately understood, and that of China in making Pakistan to do all of this consequently.

Where the current Afghan government is declared as pro-Pakistan, the centrality of its neighbor in ensuring peace within Afghanistan was never lost on it even when Karzai was in power. In fact, while signing the Strategic Partnership Agreement, Karzai had belabored to emphasize and distinguish between its ‘twin brother’ (Pakistan) and ‘a great friend’ (India). Might I say blood is thicker than water?

To add to this, the acting Minister of Defense, Mohammed Masoom Stanekzai, had recently told in an interview to an Indian channel that Afghanistan will be inclined to take help from wherever it comes so long as it does not hamper their interests. India is but one of their options, but yes a significant one given the other investments India has made in Afghanistan.

No matter how theoretical this might sound, but in an anarchic world where survival is based on self-help, both India and Afghanistan as sovereign nations are doing what is best in their interests. India’s conspicuous absence from Afghanistan’s military scene is driven by national interest as much as the latter’s decision to involve Pakistan is. Yes, it is strategically a situation India wished it could have avoided, but this is something that it cannot control. What India can control is its approach to Afghanistan which needs to be tempered in a way that does not betray it as a disgruntled ‘big’ brother who is upset over being ‘snubbed’. There is no snubbing, only actions taken in self-interest.

The deteriorating security situation in the whole of South Asia is worrisome, with the ISIS already at the door. In these circumstances, it is crucial for India to bolster Afghanistan’s security; a country which is technically the gateway to South Asia. This is needed not only to fulfill the commitments India has made to this newest member of South Asia, but also because it is in India’s own interest to keep its ‘strategic backyard’ safe.

Capacity building projects, where India has been Afghanistan’s reliable partner, can be pursued more aggressively to make up for what it cannot do on the hardware front. Pakistan ought not to be allowed to outrun India in this regard (Afghan cadets are trained in Peshawar too) for that might just become a double-whammy for it.

What India can also do, and for which Afghanistan has enlisted its help in the past too, is to assist this country in upgrading and refurbishing the cache of arsenals already available with it. In line with the Indian policy towards Afghanistan, the extension of Indian technical assistance will be akin to hitting two bull’s-eyes with one dart: one, it will ensure that Afghanistan is better prepared to handle its security concerns, which is also a strategic concern for India; second, it will also imply India’s presence in Afghanistan’s security circles.

As the South Asian giant, it will be in India’s interest to see to the creation and sustenance of a stable Afghanistan. For Afghanistan, the alleviation its security predicaments will be the first, formidable step towards political, economic and social stability. In these circumstances, both India and Afghanistan ought to look for newer ways to stay relevant to the other and work on them. It’s time to recalibrate; reversal does not capture the mood quite well.

*Chayanika Saxena is a Research Associate at the Society for Policy Studies. She can be reached at [email protected]