Reforming Mutual Funds: A Proposal To Improve Financial Market Resilience – Analysis

By VoxEU.org

A growing class of mutual funds – those that hold mostly illiquid assets – appear to be a potential source of systemic risk. This column discusses why, and argues that converting open-end mutual funds into exchange-traded funds could mitigate the problem. When markets are liquid, exchange-traded funds operate like open-end mutual funds; but should markets become illiquid, exchange-traded funds then operate like closed-end funds and face no run risk.

By Stephen Cecchetti and Kim Schoenholtz*

US capital markets are the deepest and broadest in the world, fortifying the country’s financial system and making its assets both liquid and attractive. A major part of this capital market advantage is due to the role played by mutual funds, which provide retail investors with a low-cost means of diversifying risk while earning a market return on their savings.

However, a growing class of mutual funds – those that hold mostly illiquid assets – appear to be a potential source of systemic risk (Gelos and Oura 2015). In this column we explain why, and then go on to suggest a change that is simple to implement and might mitigate the problem.

We start by taking a step back. The primary objective of regulation is to ensure the resilience of the financial system. That means fostering resilience of both institutions and markets. Regulators typically address the first through a combination of capital and liquidity requirements, and resolution mechanisms. The aim is both (1) to reduce the likelihood that the insolvency of a financial firm will result in a cost to taxpayers (say, through the government safety net); and (2) to ensure that intermediaries collectively will continue to provide key services (access to the payment system and supplying credit) in the event that one or more firms do fail. The details matter greatly (see Cecchetti and 2015a), but this is all well understood.

Making financial markets resilient is no less important or challenging. The overarching objective is to ensure the ability of investors and institutions to buy and sell securities smoothly and continuously regardless of circumstances. This was clearly not the case in the financial crisis, when a number of markets ceased to function. Or, to put it more accurately, to the extent that sellers could find buyers, a large liquidity premium drove prices far below estimates of fundamental value. In the US, policymakers responded with public support for specific markets (including commercial paper, asset-backed securities, and mortgages) through an ad hoc alphabet soup of liquidity facilities (see here.)

As is the case with institutional regulation where macroprudential principles are now the norm, officials today see that they need to take a system-wide view of the risks posed by markets. This means addressing various aspects of infrastructure design. Earlier this year, we described how central clearing has the potential to reduce risks in derivatives markets (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2016a). And, as a part of the post-crisis reforms, much has been done (and written) to encourage the creation and use of central clearing parties (CCPs). Similarly, both researchers and policymakers have focused on making ‘systemically important markets’ – like the repo market – more robust (Acharya and Öncü 2013).

But financial instrument design has received less attention. Here, we concentrate on the risks created by the class of open-end mutual funds that hold relatively illiquid instruments. To focus this discussion, note first that this class currently accounts for only a fraction of the mutual fund universe. The lion’s share of mutual fund assets are invested in US equities that trade actively on exchanges and electronic platforms. Even in the financial crisis, when equity prices plunged, these trading systems performed well, allowing investors to sell stocks quickly, in size, and (usually) with limited price impact. Keep in mind also that mutual funds are subject to reasonably strict limits on leverage, which is the most common and important source of systemic risk in financial intermediaries.

The problem that concerns us arises from the fact that these extremely popular investment vehicles also offer liquidity on demand even when their underlying assets are not liquid. That is, the owner of a share of a mutual fund holding US corporate or municipal bonds or emerging market assets can redeem that fund, usually at the end-of-day quote (the net asset value, or NAV), whenever they wish. This is not a problem so long as the fund manager can sell holdings without a large liquidity premium to honour the redemption. But, recent research has noted that, because of the illiquidity of the assets, this may not always be the case (Goldstein et. al 2016, Qi et. al 2010). And, as a result, investors who exit early benefit if (as usual) the asset manager’s subsequent readjustment of the portfolio imposes illiquidity costs on those that remain. This first-mover advantage creates a risk of a run that is analogous to a bank run (IMF 2015, Chapter 2). While the SEC’s new rule regarding liquidity classification of mutual fund assets focuses attention on this vulnerability, and its recent authorisation of swing pricing can help to reduce it, these changes are unlikely to eliminate the challenge.

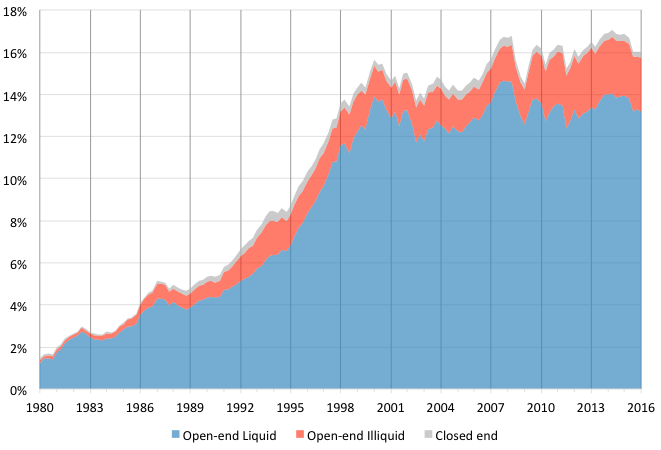

To get some sense of the size of the problem, the Figure 1 shows the evolution of assets in mutual funds divided into three categories: open-end mutual funds that hold primarily liquid assets (blue), open-end mutual funds that hold primarily illiquid assets (orange), and closed-end funds (grey). For this purpose, we define illiquid assets as those other than equities, commercial paper, US Treasury securities, and mortgage-backed securities. The data are plotted as a fraction of total nonfinancial sector assets in the US. Note that the mutual fund sector as a whole has grown enormously over the past 35 years. Starting in 1980 at less than 2% of the $8.5 trillion total, today it accounts for 16% of nearly $100 trillion. And, as the overall size of the mutual fund industry has grown, the fraction accounted for by illiquid assets –including corporate and foreign bonds, municipal bonds, and syndicated loans – has grown with it, more than doubling so that today it stands at one-sixth of the total, or roughly $2.5 trillion.

Figure 1 Mutual fund assets as a percentage of total nonfinancial sector assets, 1980-2016

Note: “Liquid” funds include money market mutual funds and all holdings of equities, commercial paper, U.S. Treasury securities, and mortgage-backed securities.

Sources: Financial Accounts of the United States, Tables L.122 and L.123 and authors’ calculations.

The overall growth of open-end mutual funds can be traced to the desire of investors to diversify their portfolios, something that surely counts as a victory for the academic finance profession. But along with this desire to reduce idiosyncratic risk arising from holding individual securities has come – at least in a substantial and rising fraction of funds – the systematic risk associated with potential runs on funds that hold illiquid assets. (For a discussion of corporate and municipal bond market liquidity – or illiquidity –see Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2015b).

Before we get to our proposal on what to do about this, it is worth asking why the open-end structure is so dominant. The alternative is a closed-end fund. While the assets in a close-end fund may be professionally managed, the number of shares is in fixed supply. Like equities, these shares trade on exchanges, with the price determined by supply and demand. As a result, in contrast with an open-end mutual fund, the price of a closed-end fund can (and often does) deviate significantly from the value of its constituent assets. But, because there is no redemption promise, there is no first-mover advantage to selling and no run risk.

Why aren’t more funds closed? Stein (2005) addressed this question over a decade ago. His answer is both simple and compelling. Asset managers are of varying quality. Investors obviously want to invest with those that are the best. How does a good asset manager show that they are good? They provide investors with the ability to take their money back if they perform poorly. Market forces oblige most managers to offer such redemption, so the vast majority of funds are open. (Stein goes on to show that as a consequence, managers also need to ensure that they do not underperform benchmarks, which means that large mispricing can persist.)

So, here is where we stand: open-end mutual funds are the norm; the fraction of illiquid assets held in these funds is high and rising; and the more illiquid the assets, the higher the run risk. Our conclusion: this expanding class of mutual funds that hold illiquid assets is creating systemic risk.

What to do? Our suggestion is to encourage conversion of this class of open-end mutual funds into exchange-traded funds (ETFs). As we explained in Cecchetti and Schoenholtz (2016a), ETFs are a hybrid between open-end and closed-end funds. They usually are based on a fixed underlying basket of assets and, like closed-end funds, their shares trade on an exchange. But, in contrast to closed-end funds, a special class of investors – called ‘authorised participants’ (APs) – has the right to create new ETF shares or to redeem old ones. The arbitrage activity of the APs in the ‘primary market’ adds to or subtracts from ETF supply when the ‘secondary market’ price (at which most ETF market participants are trading) deviates substantially from the net value of the assets that it represents.

What this means is that, so long as liquidity in the underlying assets backing the ETF is sufficient, the APs will execute an arbitrage that keeps the market price of the ETF close to the net-asset value of the underlying portfolio. But, during periods of market stress, should it become difficult to trade underlying assets, investors wanting to sell their shares may have to settle for prices below the NAV. That is, those who want to sell may have to do it at a discount. Put another way, when markets are liquid, ETFs operate like open-end mutual funds; but should markets become illiquid, ETFs then operate like closed-end funds. As a consequence, ETFs face no run risk.

This logic leads us to ask whether the systemic risk created by the combination of open-end mutual funds’ redemption rules and their holdings of illiquid assets could be mitigated if these mutual funds were converted to ETFs. From our perspective, the leading concern would be to ensure that retail investors understand that there is no guarantee of liquidity. This is a general issue with ETFs even today, since they are often a focus of high-frequency trading (including that, for example, of APs) and are used by active fund managers as a low-cost means to quickly alter their exposure. But, it would become far more important if ETFs were to replace open-end mutual funds that hold relatively illiquid assets and grow from just over $2 trillion to something closer to $5 trillion.

Returning to where we started, financial system resilience requires both resilient institutions and resilient markets. We have a reasonably good understanding of how to use prudential regulatory tools to mitigate the systemic risk caused by intermediaries and deliver the former. But ensuring continuous market function is equally important. Doing that requires that we focus on the design of both market infrastructure and securities, something that has not, in our view, received sufficient attention.

It is in that spirit that we propose studying the implications of converting a rapidly growing class of open-end mutual funds into ETFs. If the SEC is to undertake a ‘root-and-branch review’ of the ETF industry (Financial Times 2016), it ought to consider it in the context of the mutual fund industry as a whole, allowing for the serious possibility that – relative to mutual funds holding illiquid assets – ETFs could reduce systemic risk.

Authors’ note: An earlier version of this post appeared on www.moneyandbanking.com. We thank Jeremy Stein and Robert Whitelaw for very helpful conversations about ETFs and open-end mutual funds.

*About the authors:

Stephen Cecchetti, Professor of International Economics at the Brandeis International Business School

Kim Schoenholtz, Professor of Management Practice, NYU Stern School of Business

References:

Acharya, V and T Sabri Öncü (2013), “A proposal for the resolution of systemically important assets and liabilities: the case of the repo market,” International Journal of Central Banking 9(1): 291-351.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2015a), “Bank resilience: yet another missed opportunity,” www.moneyandbanking.com, 30 November.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2015b), “Bond market liquidity: should we be worried?” www.moneyandbanking.com, 17 August.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2016a), “Making markets safe: the role of central clearing,” www.moneyandbanking.com, 28 March.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2016b), “The world of ETFs,” www.moneyandbanking.com, 1 August.

Financial Times (2016), Robin Wigglesworth, Nicole Bullock and Joe Rennison, “SEC preparing large-scale review of exchange traded fund industry”, 20 October.

Gelos, G and H Oura (2015), “Asset management and financial stability”, VoxEU.org, 25 July.

Goldstein, I, H Jing and D T Ng (2016) “Investor Flows and Fragility in Corporate Bond Funds,” unpublished manuscript, Wharton School, May.

IMF (2015), Global Financial Stability Report.

Qi, C, I Goldstein and W Jang (2010), “Payoff complementarities and financial fragility: Evidence from mutual fund outflows,” Journal of Financial Economics 97(2): 239-62.

Stein, J C (2005), “Why are most funds open-end? Competition and the limits of arbitrage,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 120(1): 247-72.