Disarming Libya: Passive Nuclear Blackmail – Analysis

By IPCS

By Lydia Walker

With Libya’s unrest grabbing the headlines, one of the few mercies in the violent situation is that the Libyan government no longer possesses nuclear weapons materials. Imagine if they did: They could use their possession, or the lack of security of their nuclear materials as a way to gain leverage and support from the international community. This supposition is not simply theoretical – indeed, Libya attempted to do just that over a year ago when the Gaddafi regime was not in such peril. While Libya’s decision to curtail its nuclear ambitions is an important victory for the international nonproliferation regime, the path from its 2003 pledge to the actual removal of its fissile materials was rocky. Towards the end, Libya even involved diplomatic blackmail in its month-long stand off with the US, and Russia. Libya attempted to use the possibility of ‘loose nukes’ to gain leverage in negotiations. For over a month it left seven five-ton casks of uranium out in the open under light guard. While negotiations were eventually unsnarled and the uranium left the country, the difficulties involved expose the possibility of what happens when a state uses the possibility – even assists in the possibility – of ‘loose nukes’ as a strategic negotiations ploy. How can the international nonproliferation regime cope with this tactic in the future? What does the example of the eventually successful Libyan negotiations have to say about future disarmament processes?

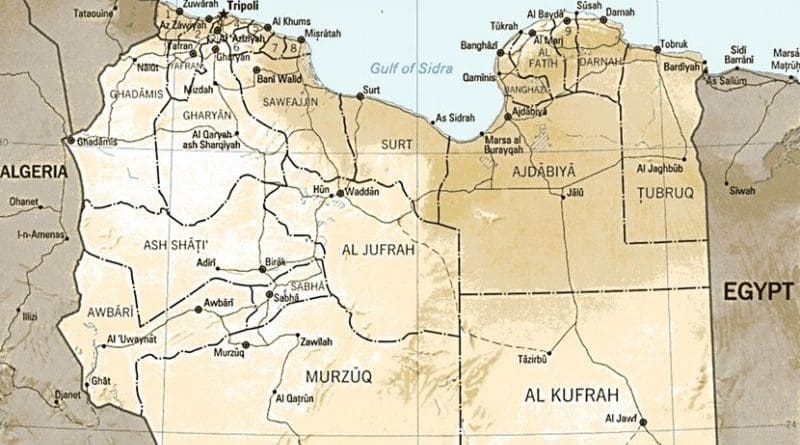

It took six years for Libya’s nuclear materials to finally leave the country. In November 2009, Libya moved the last of its highly enriched uranium from its Tajoura (near Tripoli) facility. US and Russian officials were poised to load this fissile material on to a special cargo plane bound for Russia. Then, on 20 November, Libyan authorities unexpectedly stopped the shipment. They left the nuclear materials out in the open with only minimal protections. US and Russian diplomats feared that the lightly guarded nuclear material would be easy prey for a non-state actor group. For a month diplomats engaged in complex negotiations while engineers, also from the US and Russia, worked to secure the uranium from possible theft or accident.

In this high stakes game, Libya provoked the fear of nuclear terrorism through purposeful neglect. The longer its uranium remained unsecured, the more concessions from the US it hoped to extract. US State Department documents received by The Atlantic (and confirmed by both an anonymous State Department official and an international nuclear monitor) state that following the unexplained halt to uranium removal, Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi contacted the US Embassy. Saif, often considered the more reformist of Muammar al-Gaddafi’s sons, expressed displeasure with the US. According to these accounts, Saif promised to solve the nuclear impasse if the US provided Libya with economic concessions in the range of US$10 million and ended its trade embargoes against Libya. He wanted a laundry list of military armaments, a medical facility, as well as cold cash. He also proposed a joint summit between his father and President Obama as a signal of US respect and consideration for Libya.

Libya did not receive most of these concessions and the fissile material was eventually removed after intense diplomacy in December 2009. While this episode may have had a ‘happy ending’ for the international nonproliferation regime, it exposes the dangers of low-grade nuclear blackmail. A state does not need to threaten to use its nuclear weapons or to use its fissile materials to build weapons. Instead, it can leave its weapons or weapons materials unsecured. In this way it can threaten the world passively with the rationale, “Look, we aren’t doing anything. But if you don’t help us out, some non-state actor might get a hold of them. And you wouldn’t want that to happen.”

The current unrest in Libya draws attention to how dangerous such passive blackmail could have been, were the Libyan political situation in November-December 2009 like the current. Nuclear blackmail is not necessarily a zero-sum game where an otherwise weak state promises to blow up someone else in order to maintain power. It can be used in a situation where the weak state takes advantage of its very weakness in order to extract concessions – be it money or gestures of support/legitimacy – based on the global risk caused by its weakness.

Besides underscoring the danger of passive nuclear blackmail, the Libyan nuclear disarmament case of 2003-2009 has two important points for the international nonproliferation regime: First, even seemingly direct negotiations of these sorts are drawn-out and experience unexpected road blocks. Second, the tight diplomatic coordination of the US and Russia was necessary to disarm Libya. Limited, specific multilateralism may work better than the larger Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty framework or strictly bilateral negotiations. As the stakes rise with regional realignment and current violent instability in Libya, at least we can be thankful that there is no fissile material in Libya with which the Gaddafi regime can play passive nuclear blackmail.

Lydia Walker

Research Intern, IPCS

email: [email protected]