Coronavirus Contraction: Only Cooperation Can Defeat The Impending Global Crisis – Analysis

Despite China’s success in containment, the novel coronavirus is exploding outside China, due to complacency and inadequate preparedness. The impending contraction will compound human risks and economic damage.

Although the epicenter of the outbreak is now Europe, only a few major economies have launched effective battles against the virus. Hence, the rising levels of imported cases in the borders of China and the rest of Asia.

Since complacency and inadequate preparedness prevailed outside China until recently, the consequent global pandemic casts a dark shadow over the global economy. It, too, shall pass, but only with effective global cooperation.

Extended economic impact outside China

With the novel coronavirus (Covid-19), the number of accumulated confirmed cases worldwide is exceeding 200,000 people. But in the absence of adequate testing, even these official figures are just the tip of the iceberg.

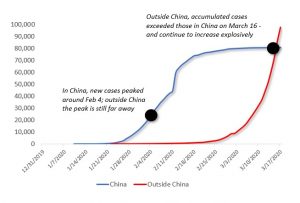

In China, the turnaround came a month after the first novel coronavirus cases were diagnosed, thanks to strong containment measures. But outside China, the first cases were reported after mid-January and they continue to accelerate and now exceed those in China (Figure).

In China, the impact of the coronavirus could ease in April. But outside China, epidemiologists currently anticipate a peak around June. If that’s the case, economic damage in China would be largely limited to the first quarter, but international economic damage would endure well into the second quarter.

Assuming the rise in new imported cases in China and elsewhere can be kept down, even this relatively benign scenario would mean adverse repercussions on the world economy.

After mid-January, I projected three probable virus impact scenarios, which can now be reassessed. In the “SARS-like impact” scenario, a sharp quarterly effect, accounting for much of the damage, would be followed by a rebound. The broader impact would be relatively low and regional. That is no longer in the cards, however.

In the “extended impact” scenario, the adverse impact would last two quarters. The broader impact would be more severe and have an effect on global prospects. That’s where the world economy is now heading to.

In the “accelerated impact” scenario, adverse damage would be steeper and even broader with serious consequences on the global economy. If the containment measures continue to fail outside China, this scenario would ensue.

In early March, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected global growth to fall 0.1 percentage points from the expected 3.3%. The estimate was too optimistic. Global growth could drop to 2.4 percent in 2020 – or worse, if infection rates continue to rise.

Contraction, stagnation, debt in advanced economies

Before the virus, quarterly growth in the Eurozone was 0.1 percent; the weakest in seven years. Now things will get worse. German GDP will continue to stall, France and Italy will remain in contraction. In the UK, annualized growth is likely to fall from 1 percent by another 0.2 percent and more. In Spain, soaring coronavirus cases will reverse the growth pickup. With debt at 135 percent of its GDP, Italy will be particularly vulnerable in 2020.

If the virus cases continue to increase in the Eurozone, regional growth could halve to 0.5 percent or worse.

In North America, local transmissions are on rapid rise, yet local testing is badly lagging. Despite greater awareness of the coronavirus and weeks of time to prepare, politization replaced mobilization, coupled with a series of missteps, including faulty and belated local testing, failures in evacuations and quarantines, lax enforcement and monitoring of self-quarantines.

Recently, the IMF projected US growth to suffer a slowdown from 2.0 to 1.6 percent. But the estimate is too optimistic. After the White House’s delays of outbreak management, the Fed cut interest rates close to zero, coupled with a new round of $700 billion for quantitative easing.

In the short-term, the move is understandable. But in the long-term, it compounds new risks. As the US national debt now exceeds $23.5 trillion (107.3% of GDP), Washington’s debt burden is at par with Italy just before its 2010 European Union (EU) sovereign debt crisis.

Moreover, the Fed’s rate cut is likely to be coupled with fiscal stimulus, which may still not suffice. Yet central banks in Europe, the UK and Japan will follow the US footprints into more monetary and fiscal accommodation. But that is likely to fail to quell virus fears, if infection rates continue to soar.

Prior to the coronavirus, Japanese growth contracted 0.7 percent in the 4th quarter of 2019. After last fall’s consumption tax and the consequent economic turmoil, contraction prevailed in January, while great uncertainty overshadows the 2020 Olympics. And Japan’s sovereign debt is already 2.4 times bigger than its economy.

In addition to Japan and South Korea, the rest of Asia’s advanced economies are in or almost in recession, including Australia and the regional financial hubs Singapore and Hong Kong. Since these countries are significant investors in Southeast Asia, their challenges will reverberate across emerging Asia.

Early damage limited in emerging economies, risks rising

In Southeast Asia, the expected 5 percent growth is now history. Even countries that have strong structural growth potential, including Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines, are not immune to indirect short-term hits as their trade, investment, migration and remittance flows depend on international environment.

The same goes for South Asia, particularly India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. In India, the growth rate in the past two years has decelerated from 7.7 percent to 4.7 percent in January. The impact of the global pandemic will compound such threats.

Before the crisis, Chinese economy was still benefiting from a mild recovery. Recently, the IMF anticipated China’s growth below 5.6 percent. US analysts anticipate baseline growth of less than 5%, with significant downside risk. However, if China can limit the adverse impact mainly to the first quarter of this year, a variation of the rebound story is still possible.

The real risk in China and other large emerging economies is the potential negative feedback effect from the world economy in the second quarter. While virus cases have so far been low in Russia, it will be penalized by oil prices, just as Brazil’s growth has been harmed by the fall of commodities.

In the Middle East, too, virus cases are climbing, from the Gulf to Egypt and Northern Africa’s Maghreb economies. In Iran, US withdrawal from the nuclear deal and incessant efforts at destabilization have been accompanied by a severe outbreak of the novel coronavirus, which will cause further economic erosion.

Sub-Saharan Africa is already struggling with a lingering Ebola crisis in the West and locust plagues in the East. Official virus cases are still low (South Africa, Nigeria, Senegal), but tests have only begun. In simulations, the highest importation risk involves countries (South Africa) that have moderate to high capacity to respond to outbreaks, whereas countries at moderate risk (Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sudan, Angola, Tanzania, Ghana, and Kenya) have variable capacity and high vulnerability.

Seizing opportunities and avoiding risks

If the current downside scenarios were to materialize, the net effect could mean a $2 trillion shortfall in global income. That would penalize developing economies (excl. China) by some $220 billion or more.

In such scenarios, oil exporters would be hit the worst. In the past two months, crude oil prices have halved to less than $30; $10 below the 2008 crisis plunge. While commodity exporters could lose over 1 percentage point of growth, along with those with trade exposure to the most affected economies. The misguided and badly timed oil price war will further compound the erosion.

In developing economies with weaker health systems, endemic poverty and social instability could result in a secondary epidemic with potential global impact. In this crisis, the world economy is only as strong as its most fragile links.

What is really needed is multipolar cooperation among major economies and across political differences. In this quest, China, where containment measures have been successful, can show the way, along with major advanced and large emerging powers.

A version of the commentary was released by China Daily on March 18, 2020