Russia’s Black Sea Strategy: Restoring Great Power Status – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Yuval Weber*

(FPRI) — The importance of the Black Sea region to Russian security has risen over the past decade from an area of general concern to a central theater of national defense and power projection. Russia’s security needs and stated intentions reflect local rivalries over regional dominance and international aspirations to “great power status” that harken back to earlier eras of expansionism.

In between the Middle East, the south Caucasus, the eastern Balkans, and southeastern Europe, Russia’s Black Sea aims are twofold. The first aim is the pursuit of national security, which has expanded in recent years following conflicts with Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova, additional tension with Turkey over Russia’s support for Syria, and the growing influence of NATO’s presence and capabilities, as all littoral states are either NATO members or have expressed serious desire to join the alliance. The second aim is to use increased influence over Black Sea states to aid its war efforts in Syria that buttress claims of being a “great power” able to revise the international and regional security order through projecting power abroad, conducting out-of-area military operations, and making itself indispensable to the international politics of a region not its own. Russia’s actions in the Black Sea region are guided by these two overarching aims.

Where Does Russia’s Grand Strategy Come From?

For more than a decade, President Vladimir Putin has been very clear in expressing dissatisfaction with the world order. In his landmark 2007 speech at the Munich Security Conference, the Russian president laid out his case that the unipolar world with the United States at its head was unfair and dangerous. He rhetorically asked, “What is a unipolar world? No matter how we beautify this term, it means one single center of power, one single center of force and one single master.”

Americans and Europeans generally praise the expansion and deepening of European political and economic structures, but the Russian perspective is quite different. In the common Russian view, during the 1990s and early 2000s, the Kremlin was forced to accept bad deals repeatedly when it was unable to resist. Dissatisfaction with unipolarity and American leadership led Russia to redefine its global aims as curtailing the United States’ leading role and promoting a new global security architecture based on decentralization of power. By limiting the reach of any one state, the outcome would acknowledge spheres of influence.

Russia’s general strategic aim worldwide is multipolarity and the end of NATO’s security monopoly in continental Europe. Its policies in the Black Sea region fulfill this strategy in two ways. First, by refusing participation in regional organizations (detailed below), Russia inhibits the effectiveness of these organizations and thus maintains emphasis on bilateral relationships in which it possesses a power advantage. Second, by supporting separatists in frozen conflicts such as in Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine, Russia deters further regional expansion of NATO by raising the political costs of military cooperation with states hosting active conflicts on their legal territory.

Following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the dissolution of Soviet power and influence created two complications for Russian leaders. The first was the loss of informal control over Romania and Bulgaria as those countries transitioned away from communism and the collapse of formal control over now-independent states such as Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia. The second was the reduced extent of Russian borders that left both ethnic Russians and groups of people seeking Russian protection beyond the formal reach of Russian authorities.

The complications of loss of formal control and informal influence saw regional states seeking admission into Euro-Atlantic political, economic, and security organizations, and Russia seeking to maintain links and to provide armed support to ethnic compatriots or allied groups wherever possible. Over the past 25 years, this policy has resulted in Russia resisting European Union entreaties in the region, including inter alia, the Black Sea Strategy, Black Sea Synergy, Black Sea Forum for Partnership and Dialogue, and the Eastern Partnership, preferring to keep European bodies out and its own relations with regional states on a bilateral basis where its own power could dominate in.

Second, to maintain power differentials and inhibit the process of Europeanization in the region, Russia’s relations with post-Soviet states have been a mix of supporting separatists to weaken territorial integrity and state capacity and the using military force directly. A survey of the region tells a grim tale beyond Romania and Bulgaria, both of which moved quickly to integrate with the European Union and NATO.

Regional Issues in the Black Sea

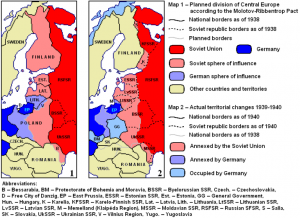

In Moldova, ethnic Russians were moved into the region from 1940 onwards following Bessarabia’s annexation from Romania during World War II as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact to colonize the area and neutralize the local population. In March 1992, hostilities between Moldavans and Russians erupted over the direction of the new state, with the latter predominating in Transnistria and showing concern over language policy, potential reunification with Romania, permanent minority status, and loss of economic links as an exclave far beyond Russia’s borders. The fighting ceased when the Soviet 14th Army, ostensibly supposed to hand over its equipment to the newly-created Moldovan Defense Ministry, instead intervened in the fighting on the Transnistrian side and severed Moldovan control over that territory.

In Moldova, ethnic Russians were moved into the region from 1940 onwards following Bessarabia’s annexation from Romania during World War II as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact to colonize the area and neutralize the local population. In March 1992, hostilities between Moldavans and Russians erupted over the direction of the new state, with the latter predominating in Transnistria and showing concern over language policy, potential reunification with Romania, permanent minority status, and loss of economic links as an exclave far beyond Russia’s borders. The fighting ceased when the Soviet 14th Army, ostensibly supposed to hand over its equipment to the newly-created Moldovan Defense Ministry, instead intervened in the fighting on the Transnistrian side and severed Moldovan control over that territory.

The territorial status quo of this frozen conflict has remained to this day. Attempts to resolve the conflict failed in the early-2000s because the West expressed concerns that a federal arrangement between Moldova and Transnistria would prove unworkable as Russian military presence would be guaranteed for another 20 years alongside constitutional veto held by Transnistria. The net result has been a frozen conflict with no reasonable expectation of resolution, which has hampered Moldova’s desires to join the EU and NATO.

In Georgia, post-Soviet withdrawal of Russian power was met by an ethnic nationalist Georgian government under Zviad Gamsakhurdia. This government sought to deny Abkhazia and South Ossetia—two autonomous regions in the Soviet period—continued political rights and civil protections to its citizens, precipitating conflicts with both. The Abkhaz and Ossetians were able to draw upon their populations fighting for existential survival as well as indigenous “Mountain People” and Islamist resistance from the North Caucasus, that is, different groups seeking to create new polities based on ethnic or religious solidarity. They also received support from Russian state and non-state military actors to defend themselves, forcing the Georgians to sue for peace.

This state of affairs lasted until a change in government in 2004 brought Mikheil Saakashvili to power in Georgia, who set the country on a much more ambitious course to join NATO and the EU, which, unsurprisingly, conflicted with Russia’s aims to prevent that particular outcome. In August 2008, war erupted over Georgian attempts to assert sovereignty over Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which was decisively resolved by Russia’s intervention on behalf of the residents of Abkhazia and South Ossetia—who had been receiving Russian passports en masse to allow Russia to intervene on behalf of its threatened citizenry. The net result has been a frozen conflict with no reasonable expectation of resolution, which has hampered Georgia’s desires to join the EU and NATO.

In Ukraine, the political events of the past three years have dominated Russian external affairs. Prior to the Maidan protests that saw President Viktor Yanukovych chased first from Kiev and then from Ukraine altogether, Ukraine had been the juiciest fruit left on the vine in terms of eastward European expansion and westward Eurasian expansion and was the recipient of two very different integration offers. The EU offered an association agreement and a deep and comprehensive free trade agreement that would put it on the path towards membership in the EU. The Eurasian Economic Union, Russia’s own attempt to create a multilateral political and economic organization from which Russia could stake its claim as the head of a regional organization, offered a customs union that would maintain and deepen the status quo relations between Ukraine and its eastern neighbors.

Yanukovych initially supported the European deal, but then abandoned his pledge, leading to the civil unrest that led to his ouster. Once it was clear that any post-Maidan government would be pro-European at best and anti-Russian at worst, Putin ordered the annexation of Crimea to protect military assets on the peninsula and military support to separatists on the Ukrainian mainland. In the years of war since, Russia has sought to keep the violence at a high enough level to prevent peace in Ukraine, but low enough to deter outside intervention or penalties tougher than the economic sanctions initially imposed. The net result has been a “hybrid” conflict with little expectation of resolution until either Kiev or Moscow collapses.

In Turkey, the tense relations over the past several years have centered around the conflict in Syria. Russia supports its client Bashar al-Assad for several reasons: to fight international terrorism (and justify its claim of great power status through provision of this critical public good even if it defines all opponents of Assad as terrorists), to support its client as a demonstration of its steadfastness, to contrast the lack of American support to allies such as Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and to become indispensable in Middle East politics. The support for Assad has caused difficulties between Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the leader of Turkey, who opposes Assad for his anti-Islamist positions. Erdoğan opposes the Assad regime for many reasons: failing to control his state and allowing violence to dominate the region and produce refugee flows that strain the Turkish state; causing terrorism to flourish, leading to Turkey being a continual victim of terrorist attacks; and inviting yet more instability to the region.

Over the past three years, as Russia has pivoted from Ukraine to Syria as its main theater of interest, Russo-Turkish relations have vacillated due to Turkish air defense shooting down a Russian fighter jet that led to Russian travel and food sanctions against Turkey; Putin offering moral support to Erdoğan when the latter was under threat from a coup attempt; and a Turkish Islamist policeman assassinating the Russian Ambassador to draw attention to Russian destruction of Aleppo. The net result is that Putin and Erdoğan now need each other to maintain the status quo: Erdoğan needs a foreign source of support given his diplomatic isolation and domestic opposition following the coup attempt and the resulting crackdown, while Putin can use Erdoğan’s relative weakness to reduce Turkish opposition to Syria, thus allowing Russia a freer hand to continue its support.

Where Will Russia’s Black Sea Foreign Policies Go?

In its larger aim to revise the regional and international security order, Russia needs to demonstrate the ability to set the rules of political, military, and economic interaction, or to carve out exceptions for itself. Around the Black Sea region, Russia pursues foreign policy on a bilateral basis to do just that, involving itself as the sponsor of frozen conflicts, the sponsor of military forces both fighting and defending central governments, and deterring NATO whenever its adversary goes on patrol in the sea and airspace of the Black Sea.

The challenge for Russia will be to maintain the status quo, which is far more expansive given the push into Ukraine and Syria, until such time as other states take open Russian power projection as a basic fact of international affairs. For such a thing to occur, Russia needs to be able to maintain separatist forces in Ukraine long enough to catalyze the collapse of the central government in Kiev and have the next government accept a peaceful resolution on Russian terms, most likely involving the acceptance of a federal structure that, like in Moldova before, accepts the regularization of Russian troops and a constitutional veto held by the regions. Moreover, Russia needs to be able to maintain the central government in Damascus to demonstrate its great power bona fides, not least of which is its rhetorical position as the leader of the anti-Islamic State coalition for which it has been seeking U.S. support.

The main challenge to the status quo is that international expansion has occurred simultaneously to domestic economic contraction. While President Putin looks to be personally very popular, social satisfaction across Russia has declined in terms of wages, purchasing power, regional debt leading to service cuts, and other economic indicators. The annexation of Crimea was very popular in Russia, but if Putin cannot generate economic growth through domestic reforms or the resurgence of energy prices, then his next term—assuming he is reelected in 2018—will be defined by the need to increase foreign victories to compensate for domestic dissatisfaction. Much to his dismay, he may find that the low-hanging fruit is gone.

About the author:

*Yuval Weber is a Visiting Assistant Professor on Government at Harvard University.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI.