The Impact Of World War I On The Arab World Today – Analysis

By Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA)

By K. P. Fabian

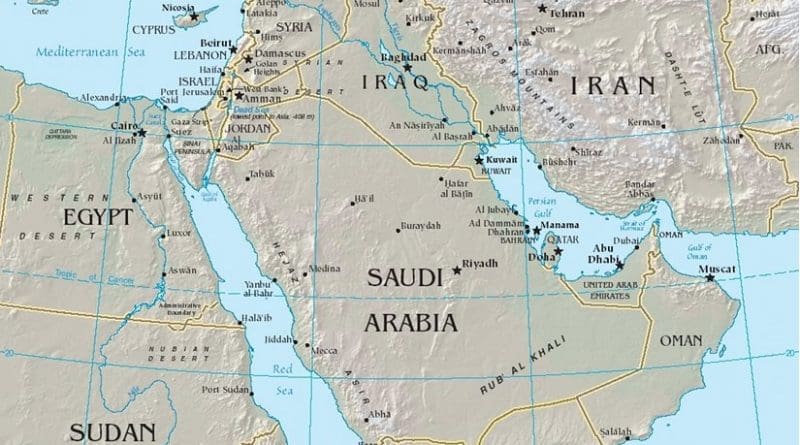

A part of the world where the impact of World War I (1914-1918) is still exceptionally strong is West Asia. The military campaigns waged during the war and the political arrangements entered into immediately thereafter eventually led to the emergence of Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Israel, and Lebanon as independent states as well as to the aborted birth of the State of Palestine. Saudi Arabia also attained its present borders as part of the same process. The Armenian Genocide of 1915-16, which the Ottoman Empire is held responsible for, is still coming in the way of successor state Turkey’s plan to gain entry into the European Union.

As Turkey entered the war on the side of Germany on 30 October 1914, London was worried that a war against the Caliph might alienate the Muslims in the Indian subcontinent and elsewhere. There was a need to collect intelligence and carry out the necessary propaganda work. Sir Mark Sykes, advisor on the Middle East to Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener, proposed the establishment of an Arab Bureau in Cairo. Accordingly, despite opposition from the Secretary of State for India, the bureau was established in 1916. The High Commissioner for Great Britain in Cairo was Sir Henry McMahon. Both Kitchener and McMahon had a strong India connection. The former was the Commander-in-Chief in India (1902-09) and his differences with Viceroy Curzon cut short the latter’s tenure. McMahon was Foreign Secretary during the 1914 Shimla Conference when the boundary line with Tibet, known as the McMahon line, was agreed upon.

In order to expedite the fall of the Ottoman Empire, generally known as the Sick Man of Europe for a long time, London decided to instigate the Arabs to rise up in revolt against the Sublime Porte as the Ottoman Emperor was known in Europe. The Ottomans were not unpopular in West Asia. But, Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, was wavering in his loyalty as he had learnt that Istanbul had some plans to replace him. As the Sharif, he held some influence. Kitchener made an appeal to Hussein to seize the opportunity to revolt. Hussein entered into a correspondence with McMahon and the two agreed that, if the Arabs revolted against the Ottomans, then at the end of the war Britain will assist in establishing an independent Arab Caliphate under Hussein. As to the area of the Caliphate, Syria, which was of interest to France, was excluded. Palestine was included in the description given by Hussein of the proposed Arab Caliphate. Ten letters were exchanged from July 1915 to March 1916 and McMahon never mentioned that Palestine should be excluded from the proposed Arab Caliphate. McMahon sent money and arms and the Arab revolt started in June 1916. T. E. Lawrence, a young intelligence officer, later named ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ in the 1962 film on his ‘exploits’, played a much exaggerated role in instigating the Arab Revolt.

The question of Palestine takes us to the Balfour Declaration of 2 November 1917. It was in the form of a letter from Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Walter Rothschild, a leader of the Jewish community. It reads as follows:

“His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

A comment is called for on the devious phrase “non-Jewish communities”. At that time, Palestine had 670,000 Arabs and 80, 000 Jews. In other words, the Arabs were more than eight times the number of Jews. Yet, they were merely ‘non-Jewish communities’. Further, they were denied their political rights, with such rights being reserved only for the minority Jews.

Obviously, Britain had double-crossed the Arabs by issuing the Balfour Declaration. They had done another double-cross earlier by concluding the secret Sykes-Picot agreement in May 1916 to divide West Asia between Britain and France. Sykes was instructed by Kitchener, even as McMahon was still corresponding with Hussein, to negotiate with the French about the disposition of territories. Georges-Francois Picot was the interlocutor representing France in the negotiations that started in November 1915. Essentially, France and Britain divided the area between themselves so as to exercise control directly or otherwise. The Syrian coast and much of today’s Lebanon went to France. Britain took direct control over central and southern Mesopotamia, around the Baghdad and Basra provinces. Palestine would have an international administration, as other Christian powers, namely Russia, held an interest in the region. And the rest of the area including Syria, Mosul, and Jordan would have local chiefs, supervised by the French in the north and the British in the south. France and Britain were dividing among themselves the skin of a bear that was still alive. Russia was consulted later and it was agreed that Russia will pick up Istanbul and control the Dardanelles. Japan, the only Great Power from Asia, was kept in the loop.

London and Paris had not, however, foreseen the Russian Revolution. The secret deal was exposed by Russian papers Izvestia and Pravda on 23 November 1917, to be followed by the Manchester Guardian three days later. There was egg on the face of the British Foreign Office. McMahon resigned in disgust. It may be noted that the Balfour Declaration and the publication of the Sykes-Picot deal both happened in November 1917.

There was another important development in November 1917. Lenin issued his Decree of Peace urging an end to the war without annexations and indemnities. Soon, President Woodrow Wilson of the US, which had entered the war in April 1917, proclaimed his famous 14 points in January 1918. The first point was about open covenants openly arrived at without secret understandings.

When the victors of World War I met in Paris, Britain took the lead, with support from France and Italy, in propagating the idea of a ‘mandate’. They needed a new term to dignify their grabbing of territory in view of what Lenin and Wilson had said. The territories held by Germany and Turkey should not be given independence straightaway as the populations were not fit for immediate independence. They needed tutoring by the victors for a while. But neither the territories nor the mandatory powers were listed in Article 22 of the Peace Treaty that brought in the concept of ‘mandate’.

In Syria, in September 1918, the Arabs promulgated a government loyal to Sharif Hussein. In July 1919, the Parliament of Greater Syria rejected any claim by France. France chose not to send in an army, but to deceive the Arabs. In January 1920, Faisal, son of Hussein, and Prime Minister Clemenceau entered into an agreement wherein France recognized Syrian independence.

France and Britain felt the need to settle the fate of the Ottoman territories in West Asia. They convened, in some hurry, the San Remo Conference (April 1920). It was attended by Britain, France, Italy, Japan, Belgium, and Greece. Britain got the mandate for Iraq and Palestine, and France for Syria. The Balfour Declaration was reaffirmed at San Remo. Technically, the mandatory powers should have waited for a formal decision of the League of Nations to award the mandate. They did not wait and acted promptly.

The San Remo Declaration was resented in Iraq where the Shias and Sunnis revolted in June 1920. Churchill ordered reinforcements from Iran and India. Gandhi urged Indians not to offer themselves as recruits to fight in Iraq. That was the first time India spoke forcefully against Britain using Indian manpower for its imperial projects. Churchill as Secretary of State for War wrote on file on 12 May 1919 that he was “strongly in favour of using poisonous gas against uncivilized tribes.” It appears that poison gas was not used in Iraq as it was not available. The revolt lost steam by October 1920.

Following San Remo, without waiting for approval of the award of mandate by the League of Nations, France sent in its army and Faisal fled. Churchill decided to have Faisal as King of Iraq. When the French made Faisal flee from Damascus, his brother Abdullah moved his forces from Hijaz to Damascus to take on the French. Churchill invited him to a ‘tea party’ and made him change his plan and rewarded him by making him Emir of Transjordan in 1921. He became King of Jordan when the country attained independence in 1946.

When the Caliphate was abolished in 1924, Sharif Hussein declared himself the new Caliph, but was not taken seriously by many. When Ibn Saud attacked Hejaz, Hussein fled as he received no help from Britain. Ibn Saud captured Hejaz, including Mecca, Medina, and Jeddah. In 1932, Ibn Saud proclaimed the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Britain worked industriously for establishing an independent state for the Jews in Palestine. Balfour himself was a Zionist. He argued that though Jews were a minority in Palestine, since it was meant to be a homeland for Jews the population of world Jewry should be compared with the population of Arabs in Palestine. Britain facilitated the entry of more Jews into Palestine and they bought land. In 1939, a British government appointed committee recommended two states, one for Jews and another for Arabs. The Jews were distressed that the Balfour Declaration was watered down. They resorted to terrorism to persuade the British to leave Palestine. On 5 November 1944, Lord Moyne, British Minister for the Middle East and a close friend of Churchill, was murdered. On 22 July 1946, the King David Hotel was blown up by a group led by Menachem Begin, a future Prime Minister of Israel. Finally, David Ben Gurion proclaimed the State of Israel on 15 May 1948, much ahead of the timetable prescribed in UN General Assembly Resolution 181 for establishing two states in Palestine not later than 1 October 1948.

Armenia was absorbed into the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century. As Armenians were Christians, their loyalty was doubted; and they, on their part, tended to look towards Russia as their protector. When Turkey entered the Great War, some Armenians helped Russia. On 25 April 1915, the genocide began. It lasted till 1922. While the exact toll is not known, 1.5 million is a reasonable estimate. Raphael Lemkin (1900-1959), a Polish lawyer of Jewish descent, coined the term genocide keeping in mind the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust. Lemkin prepared the draft of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide. After the German Parliament passed a resolution on 2 June 2016 that the killing of Armenians starting from 1915 was a genocide, President Erdogan recalled his ambassador to Germany.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India. Originally published by Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (www.idsa.in) at http://idsa.in/idsacomments/world-war-i-arab-world_kpfabian_170616

Mr. Fabian says:” As Armenians were Christians, their loyalty was doubted..” In fact, Ottoman Armenians till their rebellions were called as “Loyal Nation”. Analysis should talk on the real information.