What Does ASEAN Want From Washington? – Analysis

By Julio S Amador III and Lisa Marie Palma*

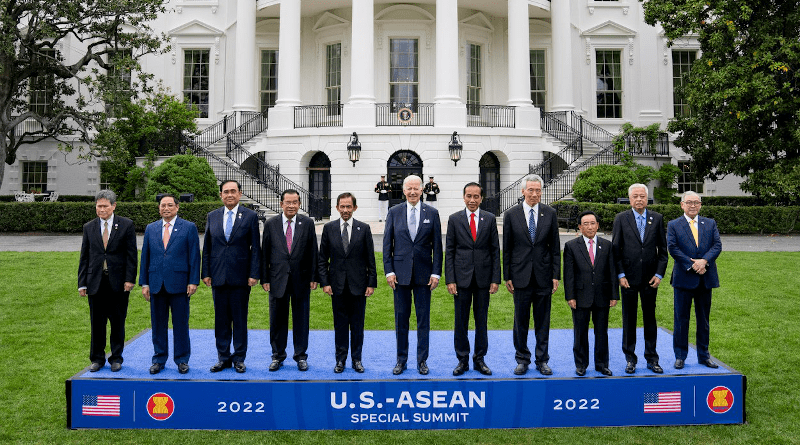

The recent high-level US–ASEAN Summit has shown that, despite challenges, there is room for productive engagement between Washington and Southeast Asia. In recognising the region’s strategic importance, the summit marked a divergence from former US president Donald Trump’s America First foreign policy. It also saw over $US150 million in investment promised towards climate action, sustainable development, education, health and maritime cooperation.

The summit demonstrated that Washington’s ‘presence’ in the region — undergirded by the new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) — is critical to the Biden administration’s competition with Beijing. But ASEAN needs to clarify what it means when it says it wants a US ‘presence’ in the region.

Since the 2010s, China has been consistent in its efforts to counter US influence in the region, with a focus on economic development facilitated through the Belt and Road Initiative and loans from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. It intensified these tactics during the pandemic through vaccine diplomacy and pandemic assistance. China has also increased its maritime capabilities and use of grey-zone activities — coercive statecraft short of war — in the disputed South China Sea.

China’s growing economic and military influence forced Biden into ‘catch-up mode’ throughout his first year in office — with US–ASEAN relations taking a backseat to the European Union, NATO and the Quad. US engagement with ASEAN member states picked-up in the second half of 2021 with high-level visits and meetings such as the and the East Asia Summit (EAS).

These efforts, combined with the recent face-to-face summit in Washington, hint at Washington’s seriousness in pursuing a stronger relationship with ASEAN. Promised investments in clean energy infrastructure, digital development and maritime cooperation are welcome outcomes that address real ASEAN challenges. Yet the summit failed to discuss the initiative most needed by the region — the IPEF.

Launched by the Biden administration on 23 May 2022, the IPEF aims to establish a connected, resilient, clean and fair economy among participants. Some argue it is more of an outline for economic engagement in trade, rule-making and standard setting rather than a trade deal. The IPEF’s main function is to project US regional influence, but the Biden administration needs to understand the domestic constraints regional countries face in trying to implement the agreement. Washington must be astute in offering incentives to make the framework appealing to ASEAN member states.

The IPEF represents a launching pad for deeper US engagement in the region. It is the first of many discussions that will allow the United States and ASEAN to identify potential areas of economic engagement.

As the region grapples with great power competition, ASEAN still believes in maintaining ‘ASEAN centrality’ to manage US–China competition. It has historically chosen a pragmatic, interest-oriented but also dangerous hedging strategy between the United States and China.

The unbridled rise of China has prompted questions about the utility of ASEAN institutional mechanisms, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum and the EAS, to constructively engage with regional powers. ASEAN member states still face aggressive behaviour from China over territorial disputes, while regional powers engage in minilaterals aimed at countering China’s influence, such as the Quad and AUKUS, rather than pan-regional forums.

ASEAN welcomed Biden’s presidency, hoping the United States would forge stronger regional ties and bring stability to the region. Yet the extent to which Washington actually wants to be involved remains unclear, so ASEAN should be transparent about what it expects from the United States. It must decide whether it wants US maritime security guarantees to counter China’s grey-zone activity, robust trade leadership in establishing an economic framework to aid the pandemic recovery, or US adherence to ASEAN centrality in dealing with human rights violations and authoritarian posturing.

Despite its ambitious goals, the United States needs to ramp up its regional ‘presence’ and avoid making empty promises as seen in their withdrawal of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and non-consultation of ASEAN member states prior to the launch of AUKUS. Its US$150 million commitment is lacking compared to China’s pledged purchase of US$150 billion in ASEAN agricultural products over the next five years. Washington’s piecemeal efforts are steps towards renewed engagement that remain insufficient to counter an assertive China.

If ASEAN wants to avoid becoming beholden to any great power, it must be upfront about what it desires from a stepped-up US presence. Economic engagement with Washington might complicate the ‘centrality’ of ASEAN in regional trade agreements, while a greater US maritime presence may invigorate China — the antithesis of what ASEAN actually wants.

*About the authors:

- Julio S Amador III is the CEO of Amador Research Services and Trustee of FACTS Asia Inc, the Philippines.

- Lisa Marie Palma is a Project Assistant at FACTS Asia Inc.

Source: This article was published by East Asia Forum

Looking at China’s actions without trying to understand the thinking process that caused such action, would lead to miscalculations.

A little history:

Nixon got China to join the US fight against the USSR. That was in the 1970s. Then, until the USSR dissolved in 1991, China had been pretty much pro-US, anti-USSR, or neutral. Starting from 1992, the US was looking to take down China. Remember the 1999 Yugoslavian bombing of the Chinese embassy and the Hainan Island incident in 4/1/2001? China was on borrowed time. Luckily for China, 9/11/2001 happened. Don’t forget that when China signed into WTO on 12/11/2001, it was viewed by many in China as signing another shameful unequal treaty. The original intent of the WTO was a semi-gutting of China patterned over the gutting of Russia after 1991. The irony is that China somehow turned the tables.

Turning point:

Then Obama’s Pivot to Asia rolled-out of the Air-Sea Battle doctrine which became official doctrine in 2010 to develop an operational doctrine for a possible military confrontation with China, rang alarm bells in China. In 2011, PLA confirmed that China was constructing at least one aircraft carrier, and began the most ambitious military buildup since WWII. China moved to start creating the artificial islands in the South China Sea in 2014.

Xi ran with that platform, and was elected President of the PRC in 2013. The Belt and Road Initiative was started the same year. Because continuity and stability are needed during extremely turbulent times, Xi moved to eliminate his term limits.

Xi and his strategies are in response to the Chinese perceived 2010 US policy change ending the peace bought by the WTO entry, in preparation for an upcoming war between the US and China.

Trump’s trade and technology war, Biden’s continuation, bipartisan anti-China agreement, overwhelmingly anti-China media and comments, are all evidence that would further strengthen their view that they did not misunderstand the 2010 US policy change.

The analysis of China’s actions changes if China believes war with the US already started, or war with the US in the near future is inevitable.