The Statesman As Ubermensch: A Nietzschean Perspective On Kissinger – Analysis

It is now not uncommon to find those with knowledge to consider both of the last two American Presidents as far from ideal Statesmen. This raises the suitability of the question regarding what is a good Statesman.

In some ways it as if the question is now emerging from hibernation to become increasingly urgent as we look forward in a world where the post-Cold War illusion of Kantian Peace seems to have given way to the old Hobbesian jungle. Technocratic, bureaucratic responses seem no longer overly relevant.

A Statesman must know how to lead, how to strategize, and, most importantly, how to create. For Statemanship is as much, or as I will argue, more an art than a science. So who and what lessons can we take in an era where leaders swing violently back and forth along a pendulum between hubristic overextension and ideologically blinkered retrenchment? What lessons can we learn in a world where our institutions of higher learning attempt to quantify everything, even the very nature of man himself?

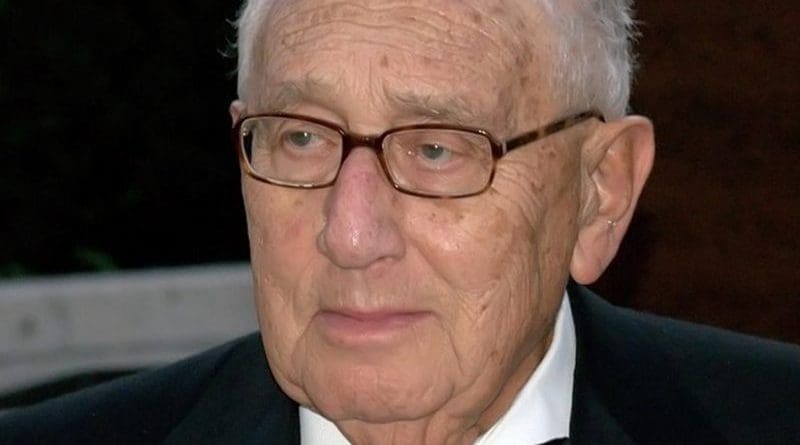

As with so much recent American diplomatic history, one can make a cogent argument that an answer can be found in the person of Henry Kissinger. Not only is he, arguably, the most famous former Secretary of State of the past half century purely within the foreign policy arena (Colin Powell and Hillary Clinton representing multiple personas within the public eye), but, like the venerable George F. Kennan, Kissinger is an intellectual giant complete with a unique insight as a practicing historian prior to entering the halls of power.

It is likely that more ink has been spilled explaining the intellectual formation and views of Kissinger than any other Secretary of State in United States history. Kissinger was an immigrant. He was a Jew whose family fled Nazi Germany before the full horrors of the Holocaust were unleashed, though he did lose family members in Concentration Camps. It is an amazing testament to America’s willingness to embrace immigrants that a man like Kissinger could have ever even have been within sight of significant government power, much less become one of it’s most significant non-Presidential wielders of it. Kissinger himself fully acknowledges this.

While much is made of Kissinger’s admiration for the Concert of Europe’s nearly century of balance power in the wake of the Napoleonic wars and his respect for the Austrian master of diplomacy Metternich; there is far more at work in Kissinger’s thought.

As a German, Kissinger was well acquainted with many of the philosophers that filled that nation’s immense pantheon of giants including Hegel, Kant, and Nietzsche. It is only natural that he would be greatly influenced by their respective works. Indeed, many historians have analyzed Kissinger’s early work, particularly his gargantuan 400 page undergraduate thesis cum magnum ops, “The Meaning of History: Reflections on Spengler, Toynbee, and Kant.” Most have come away either asserting that he imbibed the tragic spirit of Oswald Spengler or, ironically given his identification with the realpolitik school of international relations, the idealism of Kant. He was either a tragic determinist or obsessed with the inner mechanism through which man can create meaning for himself.

Studious observers have to acknowledge that while Kissinger found much of interest in Spengler, he ultimately found Spengler’s organic determinism flawed. It left no room for creativity and no room for man’s inner ability to assign meaning to his experiences. In fact, in “The Meaning of History,” Kissinger baldly states man imparts his own meaning to history, though it is through his inward experience where he learns both his limitations and worth.

This partial embrace of Kant, however, seems not to take us as far as it should in understanding much of what Kissinger later presented in both his historical and policy writing, nor how he seemed to act when wielding power.

It seems many scholars have had a tendency to overlook that the spirit of that other most famous, or infamous, of German thinkers, Nietzsche. The spirit of a man that once proclaimed that, “I am no man. I am dynamite” seems alive and well in Kissinger.

This may seem surprising given that Kissinger desired to be a builder. A builder of order would seem quite the opposite from someone that revels in intellectual bombast and the ruthless destruction of fashionable intellectual shibboleths. Yet, for anyone familiar with the works of Nietzsche, it is difficult not to sense the deeply engrained romanticism he embodied. He clung to it tenaciously even as he fought, and arguably succumbed to, nihilism.

Nietzsche is well known for many ideas, but it is the concept of “Ubermensch” or “Overman” that may well be his most controversial addition to the Western philosophical canon. Many slings and arrows have been aimed at his reputation due largely to the bastardization of this concept by the Nazis as part of their eugenic racial philosophy. Though easy to see why this is the case in an era where careful reading and appropriate contextualization is often thrown out the window, it should be pointed out that there was nothing remotely racial in Nietzsche’s original conception. Rather, the Ubermensch is one “Who has organized the chaos of his passions, given style to his character, and become creative. Aware of life’s terrors, he affirms life without resentment.”

The Ubermensch was intended to be the apotheosis of creativity, of man’s ability to transcend the abyss of meaninglessness in a world where Nieztsche famously proclaimed “God is Dead.”

Consider this, section from Nietzsche’s own magnum opus, Thus Spake Zarathustra,

“I tell you: one must still have chaos within oneself to give birth to a dancing star.”

Also consider, from Beyond Good and Evil:

He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.”

It is the ability to stare into the void and not yield that represents the strength of Nietzsche’s Ubermensch. It is also his ability to embrace the very complexity of his own chaotic soul and to create out of this chaos something of beauty that gives him purpose and allows him to be a guiding light in a world where creativity is increasingly sapped.

If the Ubermensch is Nietzsche’s hope for a man that can transcend his limits, then it is the “Last Man” that shows the end state of a man that has lost the ability to repulse even himself. From Thus Spake Zarathustra:

Lo! I show you the Last Man.

“What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?” — so asks the Last Man, and blinks.

The earth has become small, and on it hops the Last Man, who makes everything small. His species is ineradicable as the flea; the Last Man lives longest.

“We have discovered happiness” — say the Last Men, and they blink.

They have left the regions where it is hard to live; for they need warmth. One still loves one’s neighbor and rubs against him; for one needs warmth.

Turning ill and being distrustful, they consider sinful: they walk warily. He is a fool who still stumbles over stones or men!

A little poison now and then: that makes for pleasant dreams. And much poison at the end for a pleasant death.

One still works, for work is a pastime. But one is careful lest the pastime should hurt one.

One no longer becomes poor or rich; both are too burdensome. Who still wants to rule? Who still wants to obey? Both are too burdensome.

No shepherd, and one herd! Everyone wants the same; everyone is the same: he who feels differently goes voluntarily into the madhouse.

‘Formerly all the world was insane,’ — say the subtlest of them, and they blink.

They are clever and know all that has happened: so there is no end to their derision. People still quarrel, but are soon reconciled — otherwise it upsets their stomachs.

They have their little pleasures for the day, and their little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health.

‘We have discovered happiness,’ — say the Last Men, and they blink.”

The Last Men have lost their inspiration, their sense of artistry, their creativity. Even Francis Fukuyama, in his own magnum opus, “The End of History and the Last Man,” often known as the height of post-Cold War triumphalism, acknowledged that the fear of this pitiable creature may be enough to re-start the engine of history. This often overlooked element of his thinking actually raises much more interesting and profound questions than the rest of his Hegelian via Kojeve work. Note this,

The life of the last men is one of physical security and material plenty, precisely what Western politicians are fond of promising their electorates…

…Should we fear that we will be both happy and satisfied with our situation, no longer human beings but animals of the species homo sapiens?”

This is a serious warning regarding the end state of liberal, capitalist democracy as exemplified in Europe and, increasingly, in the U.S. It also raises serious questions about the quality of Statesmanship the West can look forward to in the future. Indeed, with the increasing challenge to the Western order raised by authoritarian capitalist states like Russia and China as well as the clear process of breakdown of the Westphalian state system, the need for Statesmanship has not been greater since the collapse of the Soviet Union, now nearly a quarter of a century ago.

It is not common to think of Statesman as artists. Usually Statesmen are conceived as simple politicians that may share characteristics with a sports coach at best or a talented bureaucrat. Yet, these types of figures are typically tethered to the status quo. Artists, by contrast, can exist and transcend their merely corporeal limitations. They leave monuments to posterity in their sculpture, their paintings, poems, novels, and architecture. The greatest of them leave even establish new horizons for future generations to explore. Isn’t this what Homer or Dante did? Or what Da Vinci and Michelangelo did. They used their creativity to shape inert objects and create things of such staggering aesthetic value that even centuries later, they have yet to be eclipsed. Though it can arguably be said that in the true long duree, this will fade.

Reading between the lines of much of Kissinger’s work, one senses that a Statesman can be an artist too. Rather than asculptor with his chisel and stone or a painter with his brush and canvas; a Statesman has his diplomatic toolkit with balances of power, war, peace, and order acting as their respective canvases.

How artistic a conception of statecraft are these quotes from Kissinger’s graduate thesis, A World Restored, dedicated to the craft of both Lord Castlereagh and Prince Metternich:

“The heroic figures are those who construct new worlds for themselves, who look into the abyss and choose to try to bring order out of chaos or die trying.”

There is a sense of a beauty in this conception of a Statesman. However, Kissinger, ever the European, ever the Jew who fled the flames of Concentration Camp immolation, there is also the inescapable sense of tragedy also embedded within his view. The very next line from the quote above touches on this,

“Yet, even those who successfully establish new codes, new laws, new orders cannot truly overcome the fundamental purposelessness of the cosmos.

The tragic element of human life is that there is no cure for humanity’s condition.”

The implication here seems less to embody Kant’s idealism as so many researchers of Kissinger posit and seems to veer much closer to Spenglerian determinism. Yet for the attentive reader, the imprint of the great iconoclast Nietzche is impossible not to see.

In his first set of memoirs, The White House Years, Kissinger once again borders on an explicit Nietzschean commentary:

“The statesman’s responsibility is to struggle against transitoriness and not to insist that he be paid in the coin of eternity. He may know that history is the foe of permanence; but no leader is entitled to resignation. He owes it to his people to strive, to create, and to resist the decay that besets all human institutions.”

Here too, it strains an attentive ear not to note the distinct perception of the Statesman as an almost Nietzschean, “Ubermensch.” Even if futile, his responsibility is to create new values after staring into the proverbial abyss.

A Statesman must confront the chaos of disorder in international relations. Indeed, anarchy lies at the core of the “Realist” school Kissinger is oft identified as being such an exemplar. But through that chaos, a Statesman must maintain their artistic inclinations, even if that the coin of eternity must, axiomatically, rust.

Kissinger pursues variations of this theme in other works, including a 1968 piece in the journal Daedalus, The White Revolutionary, on Bismarck. Again, one senses the admiration of creativity that was such a pivotal feature of Bismarck’s diplomacy and his greatness.

Even the most avowedly conservative position can erode the political or social framework if it smashes its restraints; for institutions are designed for an average standard of performance- a high average in fortunate societies, but still a standard reducible to approximate norms. They are rarely able to accommodate genius of demoniac power…

The impact of genius on institutions is bound to be unsettling, of course. The bureaucrat will consider originality as unsafe, and genius will resent the constrictions of routine.”

It is a clear respect that Kissinger has for genius and its ability to shatter the dullness inherent in standardized bureaucracies meant only to accommodate the mean of societal possibility. Again, though, the tragic emerges to balance the beauty, or, perhaps, in a way, to augment it.

Kissinger alludes to the fact that a nation that requires a genius in every generation is likely doomed for they are not necessarily frequent in occurrence nor are they always recognized by their societies.

Though giving birth to “dancing stars” may seem a rhetorically extravagant way of saying one is creating an art, philosophy, or even a religion; it also cuts to a pivotal component of such activities.

We return again to what it means to be an artist, especially an artist wearing the clothes, of a Statesman. As Machiavelli once said,

When evening comes, I go back home, and go to my study. On the threshold I take off my work clothes, covered in mud and filth, and put on the clothes an ambassador would wear. Decently dressed, I enter the ancient courts of rulers who have long since died. There I am warmly welcomed, and I feed on the only food I find nourishing, and was born to savor.”

So donning such wears as those of an ambassador, the Statesman as artist or as Ubermensch, seeks to go forward to create. To do so, one must understand chaos and be willing to contemplate the abyss that so much of human history has confronted, and often been swallowed by. Is it through a sense of the chaotic and tragic, that one can understand how to create? Bloodstained page after bloodstained page of history on occasion yield a respite. These are usually the creation of an enterprising leader that knows how to turn blood into wine. Think of Augustus Caesar who found a Rome made of brick and left it marble. Think of a Qin Shi Huangdi who ended the chaos of the Warring States Period to impose order. Think of aJustinian who nearly reconstituted a full Roman Empire. Think of a Charlemagne that temporarily resurrected something of the Western Roman Empire. Think of the warrior prophet Muhammad who created a new religion that would spawn multiple empires. Think of a steppe warrior named Temujin who would bring the factional Mongols together and unleash them to conquer the greatest land empire in history, even bequeathing a dynasty to the two millennium history of China.

Of course, this list can go on ad infinitum. Each of these leaders were indispensible in their capacity to create, even if what they created wrought destruction. Are these figures, in a profoundly deep sense similar to the artists referred to previously?

Kissinger, in his doctoral thesis, A World Restored, noted that Statesman can come in multiple stripes and hues. Some can erect long-standing edifices others essentially debase them:

“But the claims of the prophet are sometimes as dissolving as those of the conqueror. For the claims of the prophet are acounsel of perfection, and perfection implies uniformity. Utopias are not achieved except by a process of leveling and dislocation which must erode all patterns of obligation. These are the two great symbols of the attacks on the legitimate order: the Conqueror and the Prophet, the quest for universality and for eternity, for the peace of impotence and the peace of bliss.

But the statesman must remain forever suspicious of these efforts, not because he enjoys the pettiness of manipulation, but because he must be prepared for the worst contingency.”

Overall, these are not mere rhetorical flourishes. They are windows into Kissinger’s views and paint a portrait of a person long struggling to find meaning in life and a sense of transcendence. Yet, if all human existence is transitoriness, or as Kissinger says in his undergrad thesis,

“Transitoriness is the fate of existence. No civilization has yet been permanent, no longing completely fulfilled. This is necessity, the fatedness of history, the dilemma of mortality;”

Does not a man become quite mired in the muck of human experience? Can he escape?

This is, ultimately an existential question. Nietzsche tried to accomplish this through creativity. Though often labeled a simple nihilist, Nietzsche was actually attempting to avoid succumbing to the emptiness inherent in a purely nihilistic view of the world. One can argue that he failed in this task and may well have become an even more thoroughgoing nihilist as aconsequence.

In a similar vein, it seems Kissinger; through the canvas of geopolitics and grand diplomacy, tried to impart his inner meaning onto the contours of the world and onto history. Kissinger attempted to connect philosophy and statesmanship in a meaningful way, something that many policymakers do not do in an age where empiricism and technocratic solutions seem paramount. Yet, Kissinger fundamentally acknowledged that a Statesman is not paid in the coin of eternity. It’s creation too fades in the sands of time proving, once more, the folly of Ozymandias.

Despite this tragic sensibility, the wise Statesman as Kissinger perceives him, the true “realist”, understands the limits of what he alone can do and hopes to follow Bismarck in waiting “until he hears the steps of God sounding through events, then leap up and grasp the hem of his garment.”

A statesman is an artist, not a technocrat. Temporary as his work might be, it remains his duty to create anew structures and patterns of relative peace and stability despite the vagaries of historical contingency. In this, the Statesman is arepresentative, perhaps even the exemplar par excellence, of the Ubermensch.

So even if haunted by the specter of no transcendence, trudge along like Nietzsche’s Zarathustra they must.

This brings us full circle to our present day where the world seems aflame with the atrophy of all that the West, particularly America, has taken for granted since the end of World War II. Our present leaders seem to seek the legal codification of order. In this, they may think they are creating a framework worthy of an artists’ conception. They may think they are perfecting that which is already the best there is, perhaps, fulfilling Fukuyama’s “End of History” despite seeming evidence to the contrary of its validity.

But it is unclear that law and order is the way of the world. Power still reigns and the “Better Angels of Nature” are not necessarily fluttering to our shoulder as Steven Pinker might say. No, rather than trying to improve a rickety edifice, a real Statesman would find a new order to create. Like Nieztsche’s Ubermensch, maybe even like the Machiavellian Prince, a real Statesman will stare into the abyss and accept those things most shudder from. They will become akin to a Shakespeare, not another Monster. For so long as it lasts, it can be a thing of beauty.

This is far from an easy task. It is also not a technical task that can be assigned an algebraic formula and emerge with a clear-cut, obvious answer. It will require sensitivity, subtlety, and intuition. It is an artist’s task. Kissinger’s life long corpus of work gives us insight into this notion as does our Nietzschean friend Zarathustra…

*Greg R. Lawson, Contributing Analyst, Wikistrat