Iran’s Revolutionary Influence In South Asia – Analysis

By Husain Haqqani*

Soon after Iran’s Islamic revolution in 1979, its leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini declared that Iran would challenge “the world’s arrogant powers” across the globe. 1 “We shall export our revolution to the whole world,” he announced, adding that “Until the cry ‘There is no God but God’ resounds over the whole world, there will be struggle.’” 2

The idea of exporting Iran’s ideology was also incorporated in the Islamic Republic’s constitution. Article 154 of the current Iranian constitution affirms that Iran “supports the just struggles of the mustad’afun [oppressed] against the mustakbirun [tyrants] in every corner of the globe.”

As is often the case with revolutionary regimes, the early fervor of the Iranian revolution seems to have subsided and the broader goal of replicating the Islamic revolution has been modified to expanding Tehran’s influence and ensuring external support for the survival of its clerical regime. But Iran still pursues a robust policy of cultivating and deploying proxies in other, mainly Muslim countries.

The role of Iran’s proxies and allies in the Middle East is well known, partly because it is more overt. Hezbollah’s targeting of Israel and its efforts to dominate Lebanon, Iran’s role in propping up the Bashar Assad regime in Syria, or its political and militant meddling in Iraq and Yemen often make headlines. But the Ayatollahs have also expanded their influence across South, Central, and East Asia without attracting the same level of attention as their activities in the Middle East.

Seeking Leverage, Spreading Ideology

Iran’s goals in Asia appear to be expansion of economic and political leverage, spread of Islamist ideology, and the recruitment of cannon fodder for its proxy wars. It also hopes to keep in check the influence of Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United States. Tehran has built deep influence among the populations of its neighbors, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. The Ayatollahs’ regime also maintains close relations with the Government of India, which has security concerns over Iranian influence domestically but which also sees Shiism as a Muslim bulwark against Sunni radicalism.

A large Iranian diaspora, and cooperation in nuclear technology, characterizes Iran’s ties with Malaysia. Under its former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammed, Malaysia even joined Turkey’s President, Recip Teyyip Erdogan, and the Iranians in trying to create an alternative to the Saudi-led Organization of Islamic cooperation (OIC).

The country with the world’s largest Muslim population, Indonesia, remains wary of Iranian ideological influence over its Muslims, as does Singapore. But Indonesia and Singapore maintain economic relations with Iran. Even Thailand, which has a Muslim minority comprising under five percent of the population, has been used by Iran as a source for black market weapons.

Iran’s clerics have a natural affinity with Shia Muslims, many of whom look to Iran for spiritual and political support. The overwhelming majority of Asia’s Muslims are Sunnis and few Sunnis these days have any sympathy for Iran, unlike in the earliest days after the Iranian revolution. Then, Sunni Islamist groups also looked toward Tehran until the Iran-Iraq War, and the portrayal of Iran as the center of Shia revival, turned most Sunni Islamists away from the Ayatollahs.

Given the huge population sizes, even minorities in larger Asian countries number in the millions. That allows the Iranian Ayatollahs to cultivate Shia populations that can be influential even when they represent a smaller percentage of the overall population. For example, only 20 percent of India’s Muslim population of 195 million is Shia but India cannot ignore 40 million people. Similarly, Pakistan’s 15 percent Shias add up to 30 million and in Afghanistan they number around six million.

The Shia presence in East Asia is less pronounced but still significant. Of 230 million Muslims in Indonesia, an eighth of the world’s total, less than one million (including foreigners living in Indonesia) are Shia. Malaysia and Indonesia refuse to recognize Shia teachings, actively suppress Shia movements and Malaysia has sometimes even arrested Shias for publicly practicing their faith.3 But both countries are liberal in issuing residence permits to Iranian students and businessmen, making it possible for Iranians to bypass international sanctions. 4

Creating Pockets of Influence

Iran’s current strategy for creating pockets of influence in Asia is based heavily on cultivating Shia populations while dealing pragmatically with the governments of various countries. Every now and then, Iran’s leaders still speak of Pan-Islamic ideals just as Khomeini insisted that the 1979 revolution was not just Shia but an Islamic revolution. 5

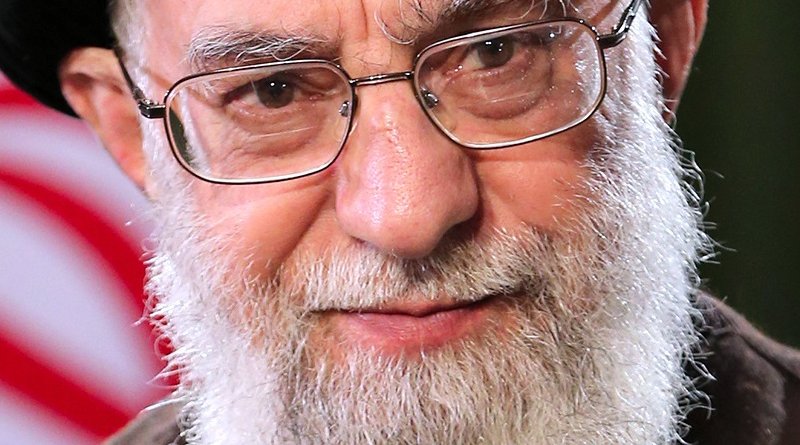

The current Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, often speaks of the “wave of Islamic revival [that] has swept through the Islamic world.” According to Khamenei, Iran’s “revolution could not be exported, since it is not a commodity. However, our Islamic revolution, like the scent of spring flowers that is carried by the breeze, [has] reached every corner of the Islamic world and brought about an Islamic revival in Muslim nations.” 6

Khamenei often includes non-Middle Eastern Asian countries while discussing the problems confronting “the world of Islam,” describing Iran’s South Asian neighbors as part of Iran’s regional focus. “Take a look at the condition of Islamic countries in our region ranging from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Syria to Lebanon, Palestine, Yemen and Libya,” he said in 2015. 7 But he does not hesitate to play the Shia card when necessary.

“We can see that people – in Lebanon, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and other parts of the world where there are devout Muslims and Shia – get concerned about the situation of our country,” Khamenei said in one speech. According to him, “That shows the active presence of the Islamic Republic’s thoughts in the world of Islam. The Islamic Republic has two aspects. It is republican in the sense that it represents ordinary people. It is also Islamic—that is to say, it is based on divine and religious values.” 8

Several Iranian institutions help in creating and sustaining networks of mosques, clerics, and seminaries that can influence large Shia communities. 9 This includes the Islamic Culture and Relations Organization (ICRO), an official chain of cultural centers that teaches “the ideals of the Revolution” and works to improve relations between Muslim countries. It also sponsors programs to teach Persian language and civilizational history and culture.

The Supreme Leader directly controls ICRO, making it an instruments of Iran’s foreign policy. The organization has been most successful in its soft power programs in Indonesia, Malaysia, India, and Pakistan, 10 alongside the Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation, which provides “alms and state funding to assist the ‘dispossessed’ ‘oppressed’ martyrs and veterans internationally.” 11

The Al-Mustafa International University (MIU), headquartered in Qom, has affiliated religious seminaries and Islamic colleges in over 50 countries. Thousands of foreign students are also enrolled at the university, often at no cost to them, and come to study at campuses within Iran. Many Al-Mustafa graduates go on to establish religious and cultural centers in their home countries, on behalf of the Iranian regime, creating a network of supporters of the Islamic Revolution among local populations. 12

The MIU’s influence is most pronounced in Afghanistan. In a 2014 interview, Hojatoleslam Muhammad Hassan Ibrahimi, Khamenei’s representative in Afghanistan, estimated that nearly 9,000 Afghans study in Iranian seminaries and about 10,000 Afghans in Iran’s universities. According to Ibrahimi, about 54,000 junior and senior Afghan (Shia) clerics were living in Iran, either in or outside seminaries. MIU has a branch in Kabul since 2012, making it the main institution providing administrative services and credentials to Afghanistan’s Shia clergy. 13

Pakistan – Nuclear-armed Neighbor

Among South Asian countries, Iran has targeted Pakistan for special attention, for multiple reasons. As a neighbor and the only nuclear-armed Muslim country, Pakistan is deemed important by leaders of the Islamic Republic. Pakistan’s large, and influential, Shia population had been close to Iran’s clerics even before the Islamic Revolution.

Pakistan had built special relations with Iran after Pakistan’s independence in 1947. But after the 1979 Iranian revolution, Iran’s leaders were initially wary of Pakistan’s close ties with the United States and the Arab Gulf monarchies and also resented the fact that Pakistan’s leaders had been close to the Shah.

As Pakistan’s pro-West and pro-Saudi military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq, initiated efforts to Islamize Pakistan in the 1980s, Pakistan became a center of Sunni-Shia conflict. Zia-ul-Haq claimed neutrality in the Iran-Iraq conflict but that was not enough for him to escape the personal wrath of Ayatollah Khomeini. In revolutionary Iran’s first military parade in February 1980, the Pakistani dictator (who insisted on attending) had to witness the spectacle of his own portrait being part of the portraits of world leaders over which Iran’s revolutionary guards marched as a sign of contempt and hatred.

Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization efforts brought greater Saudi funding for Sunni fundamentalist madrasas and the fear among Pakistan’s Shias about marginalization. Many of Pakistan’s leading personalities, including the country’s founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah, had been Shias and Shias had faced little organized discrimination during Pakistan’s first three decades. Pakistan had, in 1974, passed a constitutional amendment that excluded members of the relatively small Ahmadiyya sect as non-Muslims. The Shias are more numerous and no one in government supported the extension of discrimination and persecution of Ahmadis to Shias.

But, in the wake of the Iranian revolution, and particularly under Zia-ul-Haq, extremist Sunnis demanded that only Sunni jurisprudence be enforced through the Islamization of laws. At least one Sunni group, supported by Saudi donations, called for legally declaring Shias as being outside the pale of Islam. Meantime, Sunni militias started attacking and killing prominent Shias, who responded with militancy backed by Iran. In 1986, Ayatollah Khomeini issued a directive to the Iranian government to protect Pakistan’s Shia.

The Shias of Pakistan subsequently organized themselves as Tehrik-e-Jafaria Pakistan (Jafaria Movement of Pakistan) and demanded greater autonomy for Shia theologians within the country’s legal system. They generally also endorsed the leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini. 14 The murder of the group’s firebrand leader, Arif al-Husaini, by Sunni militants in 1988 created a martyr for Pakistan’s Shias. The small town of Parachinar, in Pakistan’s northwest and along the Afghan border, started being described in Iran’s media as “a second Gaza.” 15

By 1993 a Shia militant group called Sipah-e-Mohammad (SMP, the Army of Mohammad) had emerged under the leadership of Ghulam Raza Naqvi and Murid Abbas Yazdani. With Iranian financing and training, the group made a point of retaliating against Sunni extremists with assassinations and attacks on Sunni hardliners. 16

Iranian support also helped expand the network of Shia madrasas in Pakistan. At the time of India’s partition in 1947, there were 245 seminaries in Pakistan, of which only seven were Shia. By 1998, the total number of madrasas had risen to 2861, of which 47 were Shi’a. In 2002, the number of madrasas in Pakistan had increased to 9,880, with 419 Shia seminaries. Two years later, the number of Shia madrasas had risen to 458, including 84 madrasas for women. 17 Although the stated purpose of madrasas is to produce trained theologians, madrasas in Pakistan have the additional function of providing cadres for Sunni and Shia political groups.

Tehran was also believed to be behind the formation of a Shia political party, the Majlis Wahdat-e Muslimeen (MWM – Society for Unity of Muslims) in 2009. The MWM seems to be following the model of Bahrain’s Shia Al-Wefaq rather than that of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, eschewing violence and emphasizing political participation. The party says it reflects “the Shia minority’s aspirations for political representation,” denies receiving Iranian funding, but acknowledges “ideological links” with Iran’s revolutionary leadership. 18

Although it currently has no seats in either house of Pakistan’s federal parliament, it holds two seats in the Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly. It has allied with the ruling Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) of Prime Minister Imran Khan for the 2020 local elections in the northern Gilgit Baltistan region. Most of MWM’s leaders come from the Imamia Students Organization (ISO), which organizes Shia students on college and university campuses.

ISO claims to have a network of 800 branches and 18,000-20,000 male and 6000 female members. In 1989, shortly after he became the Supreme Leader, Khamenei met a group of ISO activists in Tehran. The supreme leader spoke about Muslim unity while remaining deeply anti-American and anti-West, as well as hostile to the status quo powers in the Greater Middle East including Saudi Arabia and other pro-U.S. Arab states. 19

ISO serves as a bridge between Iran and Pakistani Shia students other than the ones studying theology. The Shia madrasas across Pakistan are already dominated by faculty trained in Iran and their graduates often go for further education to Qom and other Iranian seminaries. Although Sunni extremists still call for excluding Shias from the ranks of Islam, Pakistan has managed to control the Shia-Sunni violence that reached its peak in the 1980s and mid-1990s. But the country remains a battleground for Sunni and Shia extremists still backed by Saudi Arabia and Iran respectively.

Despite the shock of Sunni-Shia violence inside Pakistan, Ayatollah Khomeini’s directive for Iran to act as the protector of Pakistan’s Shias, and disagreements during the civil war in Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan have been able to build a functioning relationship. Even as they clashed, the two countries cooperated in the field of nuclear technology. A nuclear cooperation agreement, ostensibly signed in 1986, led to several Iranian scientists receiving training in Pakistan. The A. Q. Khan network supplied centrifuge technology for uranium enrichment to Iran even though Pakistan later denied that these transfers were officially approved. 20

Still, Iran’s relations with Pakistan remain uneven. A major faction of the Baloch insurgency in the Iranian province of Sistan and Baluchestan, across the Pakistan border, has adopted jihadist ideology and is openly anti-Shia. Tehran suspects that Pakistan’s intelligence service supports the group, which operates from inside Pakistani Balochistan. Iran closed its border with Pakistan in 2009 after Jundallah attacks in Iran and then-President Ahmadinejad openly accused “certain officials in Pakistan” of supporting the insurgents on behalf of the United States. 21

Incidents such as kidnapping of Iranian soldiers by Pakistan-based Baloch insurgents and firing on Pakistani troops by Iranian border guards create tensions, in addition to the sectarian issues.

Pakistan is also unhappy over Iran’s recruitment of at least 20,000 Pakistani Shias in the Zeynabiyoun Brigade of IRGC’s Quds Force. The brigade was recruited primarily to fight in Syria and is named after the shrine of Prophet Muhammad’s granddaughter, Sayyida Zeynab, near Damascus. Pakistani Shias volunteered for the Brigade ostensibly to defend that shrine. 22

But the origins of the Zeynabiyoun Brigade might lie in IRGC’s earlier arming and training of a Shia militia in Parachinar, on Pakistan’s northwest border with Afghanistan. A Zeynabiyoun commander reportedly acknowledged ties with the Quds Force dating back to the time of the 2001 U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. After war broke out in Syria, the Quds Force tapped into its pre-existing network, and announced the formation of the militia in 2014. 23 General Ismail Qaani, who succeeded Qassem Soleimani as commander of the IRGC’s Quds Force oversaw the Zeynabiyoun, as well as the sister Afghan militia, Fatemiyoun.

Prior to recruitment, a significant number of Zeynabiyoun members lived in Iran and studied in religious seminaries in Qom. 24 Recruitment ads posted on Facebook in 2015 called for physically fit men, ages 18-35, and offered training, regular salaries, and death benefits for the fighters’ widows and children. 25 An IRGC statement in 2017 declaring “victory” against the Islamic State in Syria, said that the Zeynabiyoun Brigade vowed its readiness to fight anywhere the IRGC orders it. 26

IRGC affiliated media say that initially 5,000 Shia jihadists volunteered from Pakistan to fight in the Fatemiyoun Brigade, but additional recruitment from Pakistan led to the creation of a separate brigade comprising Pakistanis. Although the Zeynabiyoun are currently away from the country, Pakistan’s security establishment is concerned about the threat posed by returning fighters trained and controlled by Iran. That threat gives Iran leverage in its military to military and intelligence level talks with Pakistani officials.

Every now and then Iran demonstrates its covert ingress in Pakistan, which ensures that the secret services of the two countries continue to work with each other. In 2010, the Pakistan-based Jundallah leader Abdul Malik Regi was arrested by Iranian security forces as he was flying over the Persian Gulf enroute from Dubai to Kyrgyzstan. 27 The facts of Regi’s arrest remain mired in mystery, leading to speculation that Iranian intelligence was independently able to track Regi’s movements from Pakistan.

Similarly, in 2010 Iranian agents were able to free an Iranian diplomat kidnapped in 2008 in Peshawar by Sunni extremists, without any help from Pakistan’s ubiquitous security service. 28 Pakistan tends to play down Iran’s brazen interventions partly to avoid losing face over its inability to fend off such involvement and partly to avoid escalating tensions with Iran. 29

India: Relations Between Ancient Civilizations

Difficult relations with Pakistan have created an opportunity for India to develop close ties with Iran. India is the third largest importer of Iranian oil in Asia and offers the Islamic Republic an opportunity to “escape international isolation.” 30 Tehran and New Delhi cite historic ties between two old civilizations as the underpinning of their relationship. Persian was once the official language in Moghul India and Indians, even other than Muslims, see the two ancient countries tied by culture. Iranian society has appreciated Bollywood while Indian filmmakers have been inspired by Iranian ones.

But the real reasons for India and Iran maintaining close ties relate to trade, investment, and politics. India enjoys an economic advantage in helping Iran circumvent western sanctions on Iranian oil and the financial sector. U.S. sanctions and Pakistan’s policies have blocked the completion of the proposed 1724-mile Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline, which would enable Pakistan and India to use up to 40 billion cubic meters of Iranian natural gas. But even without that pipeline, Iran has served as an important energy supplier to India.

Iran’s location to the west of Pakistan enables India to leverage relations with Iran in its strategy of containing Pakistan. 31 India and Iran share concerns about Sunni Islamist radicalism and have coordinated strategies in Afghanistan to keep Pakistan’s influence there at bay. The two countries have also cooperated in developing the Iranian port at Chahbahar, to serve as an alternative trading route for landlocked Afghanistan, which is unable to trade with India because of impediments created by Pakistan. For that reason alone, even as India draws closer to the United States and Israel, it remains unwilling to jettison its ties to Iran.

According to Indian strategists, India sees Iran as its “overland gateway to the Central Asia region and Afghanistan, theatres where India seeks to deepen its economic activities and, more importantly, consolidate its presence by projecting greater power. 32 Close ties with Iran are a function of “India’s appetite for energy resources,” “a shared interest in countering Pakistan’s regional influence,” and India’s desire to seek a “balance against China, which is close to Pakistan and active in Central Asia.” 33

India considers its Iranian connection sufficiently worthy in strategic terms to ignore the Islamic Republic’s criticism of Indian actions in Kashmir. Iran considers India’s increasing economic and soft power particularly beneficial and, in return, is willing to support India’s desire to be recognized as a great power. Iranian President, Hassan Rouhani, has described “expanding relations with India in all areas is among the priorities” of his administration. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, bilateral trade was flourishing, and the two countries expected it to rise farther than its 2019 high mark of $17 billion.

India and Iran have a reason other than the strategic and economic factors they both highlight in their relationship. India’s Shia Muslim minority, estimated at 40 million, is the second largest Shia concentration in any country, after Iran with 66 million. India’s Shias have “deep ideological links with the Shia Islamic learning centers in Iran” but Indian officials have not found Shias to be involved in “transnational acts of terror.” 34

According to a Lt. General Ata Hasnain of the Indian army, himself a Shia, “India’s Shia community had kept its Iran linkage without any effect on its patriotic orientation towards India.” 35 But it is clear that by maintaining close ties to the Ayatollahs’ regime, India would like to keep things that way.

Unlike their Afghan or Pakistani counterparts, India’s Shias do not depend on Iranian support. Ayatollah Khamenei’s representative in India once remarked that there were more than ninety Shia seminaries in India and more than a thousand Indians studied at the Qom seminary in Iran. 36 But Indian authorities have found no evidence of these seminaries receiving undisclosed Iranian assistance or recruiting Shia militias. Often, radical Indian Shia preachers have thrived only after leaving India. For instance, Zaki Baqri, a Shia scholar from south India, reportedly preached “Khomeinism” but only after moving to Toronto, Canada. 37

The one region where Indians are concerned about Iran’s involvement with the Shia community is Jammu and Kashmir. Shias number between 12-15 percent of Kashmir’s population and are concentrated in the Kargil region, the locus of the 1999 mini-war between India and Pakistan. According to General Hasnain, Kargil has a population of 140,000 of which 77 percent (100,000) are Muslim. 65 percent of Kargil’s Muslims are Shias. These Shias lives in a strategic part of Ladakh, which is itself strategically important because of adjoining China.

An Imam Khomeini Memorial Trust (IKMT) has functioned in Kargil since 1979, helping the impoverished local population with charity and education. But it also propagates Iranian revolutionary ideology in addition to playing a role in local politics. Kargil Shias observe the anti-Israel Qods Day in Ramadan as directed by Khomeini, mark Khomeini’s death anniversary annually, and became prominent for coming out in streets after the killing by the United States of IRGC Qods Force Commander Qassem Soleimani.

Indian observers such as General Hasnain played down the “demonstrations in support of Iran and the assassinated Qassem Soleimani, seen in Kargil and elsewhere in India,” describing them as “only transactional in nature for the expression of solidarity.” 38 Reports of growing Iranian influence in Ladakh have not affected the Indian relationship with Iran so far. But the growth of pro-Iran entities there would definitely be an irritant in future as India starts questioning Iran’s rationale for building a radical support base within India.

Soleimani and the Qods Force may not have targeted Indian interests, but they did try, in 2012, to attack an Israeli diplomat on Indian soil. The wife of the Israeli defense attaché to India was injured after the car she was travelling in was targeted by a motorcycle-borne blast in Delhi. Two Indians, who were bystanders, were also injured. The attack came in tandem with an attack on an Israeli embassy employee in Tbilisi, Georgia, and an explosion in Bangkok, Thailand, where two Iranians were trying to assemble explosives to assassinate Israeli diplomats. 39 Indian police investigation into the attack in Delhi lead nowhere but it did result in strong private protests by Indian officials to Iran and the IRGC has not tried something similar in India since.

The botched attacks of 2012 on Israelis notwithstanding, Iran makes a clear distinction between its approach to governments it disregards in its covert operations, and governments it tends to respect or at least not provoke. South Asian countries fall in the second category. Iran’s allies, including militias recruited from amongst Shias of Afghanistan and Pakistan that work under the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), have not tried actively to overthrow governments. Instead, they serve as an instrument for bargaining, which enables Iran to negotiate more effectively with the governments in power. But the IRGC operates in tandem with the Iranian regime’s ideological and cultural thrust.

“If in the Revolutionary Guard there is not strong ideological-political training, then [the] IRGC cannot be the powerful arm of the Islamic Revolution,” a message from Ayatollah Khamenei stated in the preamble to the IRGC’s ideological-political training module from 2016. 40 The module described the group’s objective as “Exporting Iran’s Islamic Revolution” and ensuring “Survival of velayat-e faqih (doctrine of the guardianship of Islamic jurists.”

The IRGC inculcates a group identity amongst its members and trainees as “Guardians of Islam and Mujahideen” who reject nationalism and believe in themselves as “Allies of God and Imam Mahdi (Imam of the Age). Group members must conduct “Jihad as resistance” and be ready for martyrdom. They must also know that their enemies include “Polytheists”; “People of the Book” (Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians); the “Baaghi” (internal conspirators); and the Mohareb (those who wage war on God). 41

The IRGC’s ideological-political manuscripts make it clear that the IRGC’s mission is to export the revolution, which it deems divinely mandated and for which violence is justified. 42 The IRGC’s Quds Force has a budget separate from the general Iranian budget and is controlled directly by the Supreme Leader. It is important to note that, in addition to Corps and Directorates for Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan, the IRGC’s Quds Force also has directorates for Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.

Other Directorates cover Turkey and the Arabian Peninsula, Central Asian countries of the former Soviet Union, Western nations (Europe and North America), and North Africa (Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Sudan, and Morocco). 43 The organization chart of the IRGC makes it clear that South and Central Asia are important targets for Iran’s influence operations.

Iran’s Afghan Sphere of Influence

Afghanistan has been a major arena for Iran’s demonstration of its power, short of trying to wrest absolute control. Iran hosted around two million Afghan refugees during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, maintained close ties with Sunni Mujahedeen operating in Afghan provinces bordering Iran, and sponsored Shia groups in the war against the Soviets. 44 When the U.S.-backed Mujahedeen, based in Pakistan, announced an anti-communist government-in-exile in 1988, composed exclusively of Sunnis, Iran demanded representation of the Shia Hazaras.

This enabled Iran to claim a seat at the table in international efforts to stabilize Afghanistan after the Soviet withdrawal in 1989. Iran supported the creation of Hizb-e Wahdat-e-Islami (Islamic Unity Party), which united all Khomeinist factions under the leadership of Ali Mazari. During the Afghan civil war in 1992-93, Iran supported the Dari-speaking, Sunni non-Pashtun groups such as Jamiat-e Islami (Islamic Society) of Burhanuddin Rabbani and Ahmed Shah Massoud, Jumbish-e Melli (National Islamic Movement) of Abdul Rashid Dostum, and smaller Ismaili Shia factions. 45

A prominent Afghan Shia leader pointed out Iran’s “strong presence in Afghanistan,” based on “culture, customs, and language.” 46 Dari, one of Afghanistan’s two official languages, is a variant of Persian and is spoken by half of Afghanistan’s population. Although most Afghans are Sunni, some ethnicities in this multi-ethnic country are Shia. Prominent among them are

the Hazara, “a much-persecuted minority group of Asiatic origin inhabiting what is known as the Hazarajat, a region in Bamiyan and surrounding provinces.” 47

The Hazara are the largest Shia community in Afghanistan, far larger than groups like the Qizilbash, the Farsiwan, and the Sayyeds. They are also politically most influential and are concentrated in a strategically located region. The Taliban targeted them for being Shia and also because territory inhabited by the Hazara was important to control Afghanistan north, which resisted Taliban rule. The major Hazara Shia group, Hizb-e-Wahdat-e-Islami, was part of the Northern Alliance that helped Americans topple the Taliban in the aftermath of 9/11.

Iran ostensibly played a critical role in persuading the Northern Alliance to support Hamid Karzai’s nomination as President of Afghanistan immediately after the overthrow of the Taliban. James Dobbins, the American envoy to Afghanistan at the time has been quoted as saying that it was the Iranian representative, Mohammad Javad Zarif, who convinced Younis Qanooni, a powerful Northern Alliance leader, to back Karzai. Dobbins also received an offer from an Iranian general to assist in training the Afghan National Army, an offer the Americans wisely turned down.

Apart from the fact that the U.S. overthrow of the Taliban benefited Iranian interests, Iran also used its cooperation immediately after 9/11 to pave the way for negotiations with the U.S. with the aim of ending U.S. sanctions against Iran.

Since the Taliban’s overthrow in 2011, the Iranian-backed Hazaras have become socially and politically important in Afghanistan. Iran helps the Hazaras in maintaining that influence and, in return, Hazara politicians advance Iran’s sway in Afghan matters. Hizb-e-Wahdat leader Karim Khalili, has twice served as the Afghan vice president and remains close to the center of power in Kabul.48 Iran’s ability to leverage Afghan domestic politics has protected it from the United States using its military presence in Afghanistan to threaten Iran.

As mentioned earlier, IRGC’s Quds Force has also managed to raise a force of Afghan Shia volunteers—the Fatemiyoun Brigade, which some see as “Hezbollah Afghanistan.” The Fatemiyoun detachment of some 20,000 fighters has fought in Syria and several hundred have been reported killed in battles there since 2013.49 The group started out as a militia comprising Afghan refugees in Iran and Syria but now recruits inside Afghanistan as well. It is safe to assume that the Iranians will not stop at mobilizing Afghan Shia fighters for battle in Syria. Iran would also be able “to utilize these forces to further its interest in Afghanistan.” 50

Over the years, even as the U.S. had a huge military presence there, Iran has managed to secure its border with Afghanistan. It ensured the flow of water downstream in shared rivers and worked with the Afghan government on countering narcotics and dealing with its large Afghan refugee population estimated at one million. Iran has extended U.S. $500 million in aid to Afghanistan officially while being one of Afghanistan’s major trading partners. At the same time, Iran has close ties to various militias and armed groups both allied with and battling the Americans.51

Iran considers Afghanistan as part of its natural sphere of influence. But given the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan, and the fact that the Iranian clerical leadership’s closest allies in Afghanistan are an ethnic minority, Tehran moves cautiously on Afghanistan’s chess board. Iran maintains close relations with the government in Kabul and in addition to the 50 to 55 Shia members of parliament, also counts many Sunni politicians among its friends.

Iran’s Afghanistan policy is coordinated by the Afghanistan Headquarters, set up in late 2001 and located in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. But several competing centers of power, including the Supreme Leader’s Office, the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), the IRGC, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Finance, and the Ministry of Interior play a role in decisions relating to Afghanistan. 52

In anticipation of U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Iranian government has also been involved in political discussions with Taliban representatives. The Taliban and the Islamic Republic share a common enemy, the United States, and Iran has reportedly funded or supported Taliban factions to increase American losses. In doing so, Iran’s leadership seems to have forgiven the Taliban’s massacre of Shias and hostility towards Iran when the ruled over Afghanistan in 1994-2001.

The Iranians realize that the Taliban will be a major force in post-U.S. withdrawal Afghanistan. While retaining their traditional Shia and Dari-speaking Sunni partners, Iran wants to make sure that it can deal more effectively with the Taliban, if they come to power again. Iran would not like a total Taliban victory but has no hesitation in planning for it. Iran’s Afghan policy offers an illustration of the mixture of pragmatism and ideology that characterizes Iran’s strategy for influence in South Asia.

Conclusion

South Asia is next in importance to the Middle East in the hierarchy of Iran’s foreign policy and influence operations priorities. Iran maintains close ties with governments in the region, including military to military and intelligence to intelligence relations. But it also uses Shia populations in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India to cultivate a support base that can be used as leverage in negotiations with governments of these countries.

Iran’s desire for nuclear weapons makes Pakistan a country of particular interest for Iran’s Ayatollahs. Iran portrays itself as the protector of Pakistan’s Shia minority and has conducted a proxy war with Sunni extremists, some of whom have enjoyed Saudi Arabia’s support. Iranian intelligence has penetrated Pakistan sufficiently to be able to conduct independent operations, (such as securing the release of its diplomat from hostage takers in 2010) and buying used Pakistani centrifuges for uranium enrichment from the A.Q. Khan Network for nuclear materials. Pakistani authorities are concerned with Iran’s influence but must be mindful of the sentiments of Pakistan’s large Shia population.

Now that thousands of Pakistani Shia fighters have been recruited and trained as part of the Zeynabiyoun Brigade of the IRGC’s Qods Force, Pakistan will have to watch out for an Iranian controlled militia on its soil.

India does not face a similar threat from Iran as does Pakistan. But Iran has managed to cultivate strong economic and political ties with India, partly to circumvent international isolation and sanctions. India is home to the world’s second largest cluster of Shias after Iran. Although India’s Shias have, so far, not been as militant as their co-religionists in Pakistan and the Middle East, India will also have to watch out for the impact of revolutionary ideas emanating from Tehran and Qom.

Afghanistan is perhaps the South Asian country most vulnerable to Iranian machinations. Although its Shia minority represents a smaller proportion of the population than that in Pakistan or India, it is fully integrated in Iran’s strategy for Afghanistan. The Fatemiyoun militia, the Hizb-e-Wahdat political party, and pro-Iran Persian speaking Sunni politicians are all useful to the Islamic Republic’s plan to project greater power in Afghanistan—especially if and when the United States withdraws its military from that country.

*About the author: Husain Haqqani, Director for South and Central Asia for the Hudson Institute

Source: This article was published by the Hudson Institute in Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, Volume 27 (PDF)

1 Gary Sick, ‘Iran’s Quest for Superpower Status,’ Foreign Affairs, Vol. 65, No. 4 (Spring, 1987), pp. 697-715 ↝

2 Kenneth Pollack, The Persian Puzzle: The Conflict Between Iran And America, (New York, Random House, 2005), p 183 ↝

3 James Chin, ‘Soleimani killing tests Iran’s ties with Malaysia and Indonesia,’ Nikkei Asian Review, January 7, 2020 ↝

4 Ibid. ↝

5 Gary Sick, pp. 697-715 ↝

6 Supreme Leader’s speech, April 30, 2003 http://english.khamenei.ir/news/5451/The-wave-of-Islamic-revivalism-was-brought-about-by-a-breeze↝

7 Supreme Leader’s speech in a meeting with government officials and the ambassadors of Islamic countries, May 16, 2015 http://english.khamenei.ir/news/2069/Leader-s-Speech-to-Officials-and-Ambassadors-of-Islamic-Countries↝

8 Supreme Leader’s Address to People of Chalous and Noshahr, October 7, 2009 http://english.khamenei.ir/news/1193/Leader-s-Address-to-People-of-Chalous-and-Noshahr↝

9 Cenap Cakmak, ‘The Arab Spring and the Shiite Crescent: Does ongoing change serve Iranian interests?’ The Review of Faith and International Affairs, Vol 13 No 2, 2015 ↝

10 Edward Wastnidge, ‘The Modalities of Iranian Soft Power: From Cultural Diplomacy to Soft War,’ Politics, Volume 35, Issue 3-4, pp 364-377 ↝

11 Shahram Akbarzadeh, Dara Conduit, Iran in the World: President Rouhani’ s Foreign Policy, Springer, 2016 ↝

12 Tim Cocks and Bozorgmehr Sharafeddin, ‘In Senegal, Iran and Saudi Arabia vie for religious influence,’ Reuters, May 12, 2017; Hasan Dai, ‘Al Mustafa University, Iran’s global network of Islamic schools,’ Iranian American Forum, April 12, 2016 ↝

13 Mehdi Khalaji, ‘Balancing Authority and Autonomy: The Shiite clergy post Khamenei,’ Research Notes No 37, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 2016, p 6 ↝

14 Jonathan Broder, ‘Sectarian strife threatens Pakistan’s fragile society,’ Chicago Tribune, November 10, 1987 ↝

15 Alireza Nader, Ali G. Scotten, Ahmad Idrees Rahmani, Robert Stewart and Leila Mahnad, Iran’s Influence in Afghanistan: Implications for the U.S. Drawdown, (Arlington VA, RAND Corporation, 2014), Chapter III, p 28 ↝

16 Hassan Abbas, ‘Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan: Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence,’ Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point Occasional Papers Series, Sep. 22, 2010 ↝

17 Keiko Sakurai, Fariba Adelkhah, The Moral Economy of the Madrasa: Islam and Education Today, Taylor and Francis, 2011, p 103 ↝

18 Arif Rafiq, ‘Pakistan’s Resurgent Sectarian War,’ USIP Peace Brief 180, November 2014 ↝

19 Alex Vatanka, ‘The Guardian of Pakistan’s Shias,’ Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, Vol 13, p 8< ↝

20 Alireza Nader et al, Chapter III, p 25 ↝

21 Ibid. ↝

22 ‘The Zeynabiyoun Brigade,’ Foundation for Defense of Democracies One pager, undated ↝

23 Interview with Abbas, one of the officials in the Pakistani Zeynabiyoun division),” Shahid Rahimi International Institute (Iran), March 3, 2017 ↝

24 The life and times of the unfamiliar Shiites of the Zeynabiyoun Brigade),” Mashregh News (Iran), July 10, 2016 ↝

25 Babak Dehghanpisheh, “Iran recruits Pakistani Shi’ites for combat in Syria,” Reuters, December 10, 2015. ↝

26 The Zeynabiyoun Brigade’s message of congratulations to commander Qassem Soleimani),” Tasnim News Agency (Iran), November 25, 2017 ↝

27 Nazila Fathi, ‘Iran Executes Sunni Rebel Leader,’ New York Times, June 20, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/21/world/middleeast/21iran.html↝

28 CBS News, ‘Iran Agents Free Diplomat Held in Pakistan’ https://www.cbsnews.com/news/iran-agents-free-diplomat-held-in-pakistan/↝

29 Talha Ahmad, “Iran’s Proxy War and Pakistan,” Global Village Space, March 10, 2020, https://www.globalvillagespace.com/irans-proxy-war-and-pakistan/. ↝

30 Alireza Nader et al Chapter III, p 32 ↝

31 Bazoobandi, Sara. “Iran’s Ties with Asia.” In Asia-Gulf Economic Relations in the 21st Century: The Local to Global Transformation, edited by Niblock Tim and Malik Monica, 63-84. Berlin, Germany: Gerlach Press, 2013. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1df4hn2.6 ↝

32 Cheema, Sujata Aishwarya. “India’s Relations with Iran: Looking beyond Oil.” A New Gulf Security Architecture: Prospects and Challenges for an Asian Role, edited by Ranjit Gupta et al., Gerlach Press, Berlin, Germany, 2014, pp. 115–140. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1df4hpk.10↝

33 Alireza Nader, et al Chapter III, p 32 ↝

34 Syed Ata Hasnain, “Iran’s links in India: Is there a need to worry?” The Asian Age, Feb 7, 2020, https://www.asianage.com/opinion/columnists/070220/irans-links-in-india-is-there-a-need-to-worry.html↝

35 Ibid. ↝

36 Mehdi Khalaji, ‘Balancing Authority and Autonomy: The Shiite clergy post Khamenei,’ Research Notes No 37, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 2016, p 6 ↝

37 Anita Rai, ‘Can the West Dismantle the Deadliest Weapon Iran Has in Its Armory?,’ American Intelligence Journal, Vol 30 No 1, 2012, pp 84-91 ↝

38 Syed Ata Hasnain, “Iran’s links in India: Is there a need to worry?” The Asian Age, Feb 7, 2020, https://www.asianage.com/opinion/columnists/070220/irans-links-in-india-is-there-a-need-to-worry.html↝

39 ‘In 2012, Soleimani was accused of bringing Iran-Israel proxy war to Delhi,’ The Week (India), January 3, 2020 ↝

40 Translated excerpt from IRGC training module The Ways and Customs of Youth from the Viewpoint of Islam ↝

41 Ibid. ↝

42 Kasra Aarabi, ‘The Expansionist Ideology of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps,’ Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, February 2020 ↝

43 Anthony Cordesman, ‘Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, the Al Quds Force, and Other Intelligence and Paramilitary Forces,’ CSIS Paper, August 2007 ↝

44 Niamatullah Ibrahimi, ‘At the Sources of Factionalism and Civil War in Hazarajat,’ Crisis States Working Papers Series II No 41, London School of Economics, January 2009 ↝

45 Bruce Koepke, ‘Iran’s policy on Afghanistan: The Evolution of Strategic Partnership,’ SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute), 2013, p 13 ↝

46 Alireza Nader et al Chapter II, p 6 ↝

47 Ibid. ↝

48 Ibid. ↝

49 Hashmatallah Moslih, ‘Iran ‘foreign legion’ leans on Afghan Shia in Syria war,’ Al Jazeera, January 22, 2016 ↝

50 Farhad Rezaei, ‘Iran’s Military Capability: The Structure and Strength of Forces,’ Insight Turkey. Vol. 21, No. 4, (Fall 2019), pp. 183-216 ↝

51 Alireza Nader et al Chapter II, p 5 ↝

52 Ibid. ↝