Migration: A Case For Stay And Build – Analysis

Address migration’s root causes: Rather than fund walls, nations could end wars and offer development aid to help migrants at home.

By Chandran Nai*

A freighter trundles into a harbor, carrying several hundred migrants escaping war. Authorities discover them and refuse to let them disembark. The international humanitarian crisis is resolved only when desperate refugees force the issue by scuttling their ship.

This is not a story from today’s Greece or Italy, but about the Skyluck, a Panamanian freighter carrying 2,000 refugees from Vietnam in early 1979. The freighter sailed into Hong Kong, where it stayed for four months. Refugees, weary of squalid conditions, cut the anchor cable and ran aground on Lamma Island. Vietnamese refugees challenged many countries in much the same way that refugees test Europe or the United States today. Camps sprung up in poorer countries, like Indonesia and the Philippines. Wealthy places like Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and countries further abroad revealed themselves as less open than implied, often to the harsh criticism of international humanitarians.

Decades later, the South China Sea no longer has a refugee crisis. Instead, people are returning to the dynamic economies of Vietnam and Cambodia.

At the time, accepting Vietnamese refugees may have been the moral action, but it did not solve fundamental reasons why people fled. In the end, what “solved” the boat people crisis was a stable, no-nonsense government in Vietnam pursuing a platform of growth and development on its own terms, with the hard work of those who stayed behind and sacrificed.

Building a nation is hard work, especially after the destruction and deprivation of war and colonization. It is often easier for those with resources to pursue a better life elsewhere than to stay and build. The mindset of those who leave is understandable: Opportunities in wealthy countries appear potentially safer in the short term. Yet for many migrants, such moves lead to a life of regret in a foreign land, shaped by an inability or unwillingness to assimilate or a resentment borne out of isolation and discrimination.

“Brain drain” and “brawn drain,” taking able-bodied and educated people and under-employing them in developed ones, is clearly harmful to developing countries. One encounters countless trained engineers, doctors and other professionals working as shopkeepers, domestic help and taxi drivers in Australia, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. This trained professional workforce endures pain of a different sort while exacerbating a dire situation at home.

Richer countries, in general, take pride in being open societies, especially when migrant flows are small and made up of the skilled and talented. But when migrant flows increase dramatically, as they did in Southeast Asia during the 1970s and 1980s, or in Europe today, this rhetorical commitment becomes more difficult to sustain. In addition, as globalization chips away at the economic privileges of the richer nations and creates a more level playing field, resentment has increased towards immigrants. In Europe, the migrant crisis has empowered several reactionary and populist movements, some of which openly cross the line into discriminatory rhetoric. And while there is a basic humanitarian obligation to absorb people in dire straits it is only realistic to recognize that no country – no matter how liberal and democratic – can or will accept an endless stream of people without conditions. Politicians see to that.

The world can no longer hold on to the illusion that citizens from poor and badly governed places will always have an option to escape for the liberal West. The truth is that the doors have been slammed shut. Former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton conceded this in an interview with The Guardian, expressing admiration for the “generous and compassionate approaches” taken by leaders like Angela Merkel, yet noting, “it is fair to say Europe has done its part,” adding if societies don’t “deal with the migration issue, it will continue to roil the body politic.”

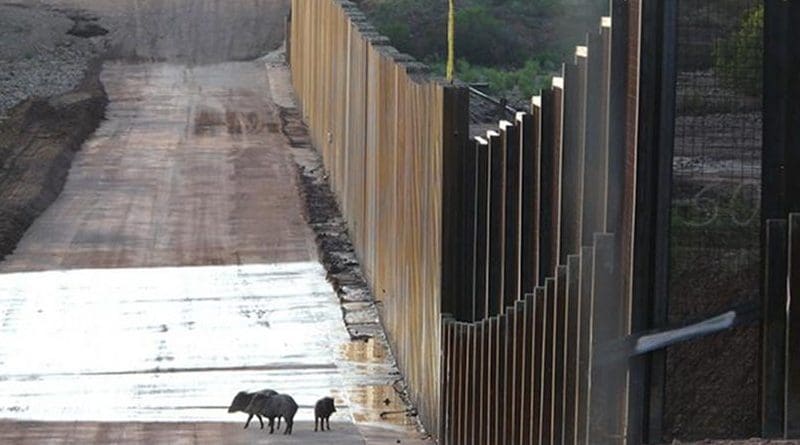

The world must better manage global migration flows, but really solving the problem requires improving opportunities in developing countries, avoiding tragic interventions by foreign powers, often led by the United States, and resolving conflicts as they arise. Closing borders, whether by tightening controls or constructing physical barriers, is not the answer. Anyone desperate enough to leave can evade controls, and others happily smuggle people, worsening tensions: Anti-immigration forces point to “increasing” illegal migration, while pro-immigration groups criticize harsh enforcement.

Ultimately, the only way to solve the migrant crisis is to improve economies and living standards in the most vulnerable countries, encouraging skilled and competent people stay and build the country. Stability while being poor is better than being poor in an unstable environment.

Interventions in the Middle East and North Africa created instability, triggering mass movements of people. Developed countries need to find ways to understand this simple equation and instead invest in an approach to support people building their lives where they are. For example, in the aftermath of conflict in Vietnam and Cambodia, Asian countries helped these countries rebuild. Japan offered development aid to countries throughout Southeast Asia, sometimes ignoring Western sanctions, betting that improved living conditions would secure these societies better than lecturing and isolation. This has been borne out in Vietnam, now a Southeast Asian economic power in its own right.

Mexico’s new President Andrés Manuel López Obrador after his election made a similar offer to President Donald Trump: Obrador would limit migration from Mexico into the United States in exchange for development aid. Obrador understands that a developed and stable economy would do more to limit migration than any wall Trump might build. Admittedly, the United States has an easier situation when it comes to working with its neighbors to control migration. Latin America countries are, with a few exceptions, functioning states and largely democratic.

Europe’s problem is tougher. Migrants come from nearby war zones, authoritarian, corrupt, crumbling and conflict-ridden. But if Europe wants to limit the flow of migrants, it must start working to improve the governance, economy and social framework of these countries rather than try foreign-policy adventures or military interventions. In this regard, the United States is culpable as its actions have been central in destabilizing the Middle East, including the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, and North Africa. Europe must revamp its foreign-policy positions on the Middle East independent of the United States – by helping countries resolve political tensions or violent conflict, even if that means talking to governments they find odious. It means keeping an eye on long-term economic, social and political development, moving beyond current approaches to aid with conditions and working with governments on their terms, not dictating to them. In poor developing countries where there is no outright war and collapse, Europe must refrain from encouraging elites and intellectuals to seek a better life in the West, supporting them to become armchair revolutionaries undermining the governments of their home countries from afar. Instead, Europe should support leaders to work within their countries and existing institutional structures, with the goal of improving them over time. This means abandoning the pretext of a higher moral ground when advancing geopolitical and other interests.

For example, the most effective action Europe can do to limit the flow of Syrian refugees is to help end the Syrian Civil War – that requires talking to President Bashar al Assad and involving him in reconstruction. Europe will find willing partners in China, Japan, Korea and Singapore to create jobs and restore confidence, peace, stability and economic opportunity. Then the migrant and refugee flows will ease. People will even return to avoid the indignities of being a “migrant.” Europe would be the beneficiary of growing economies in the Middle East and North Africa. Until then, refugees will keep trying to escape devastation in Syria, Libya, Yemen, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Putting up walls and barriers to stop refugees fleeing devastation, while refusing to talk to leaders or end conflict, only perpetuates the refugee crisis and the ugly industry that has grown around this human tragedy.

*Chandran Nair is the founder of the Global Institute for Tomorrow (GIFT) and the author of The Sustainable State: The Future of Government, Economy, and Society. Read a review of the book.