Action On Pontifical Secrecy Widely Praised, But US Catholics Still Waiting On McCarrick – Analysis

By CNA

By JD Flynn

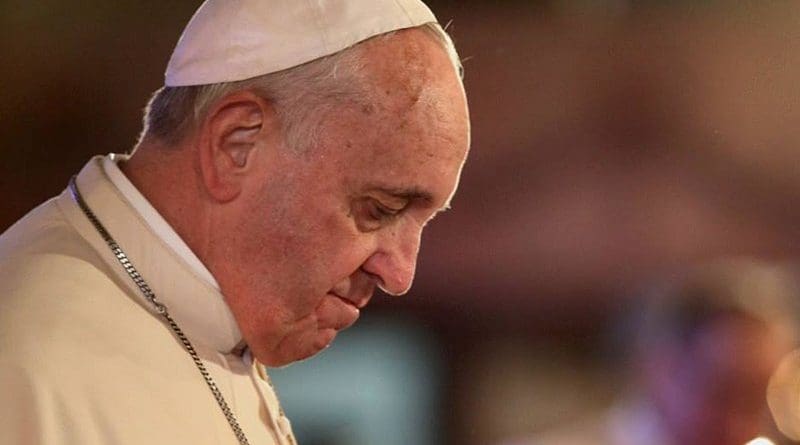

In a pair of unexpected decrees issued Tuesday morning, Pope Francis removed the obligation of pontifical secrecy from clerical sexual abuse cases, and strengthened the Church’s canonical prohibition against clerical possession of child pornography.

The moves are the latest in a series of efforts by the pope to reform the Church’s approach to clerical sexual abuse and coercion, and sure to be welcomed by Catholics calling for reform on the issue. The legal changes come, however, as observers watch to see how Francis will act on several high-profile abuse cases.

The pope’s decision to end the obligation of pontifical secrecy on cases of abuse, coercion, or possession of child pornography is a move that some reformers and abuse survivors have called for since the emergence of the Theodore McCarrick scandal in June 2018. In fact, the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors recommended the move in 2017, before the McCarrick scandal exploded.

Formally speaking, the pontifical secret binds the secrecy of procedural and substantive acts of a canonical case concerning clerical abuse or coercion, or did, until the pope amended the Church’s law this week. This means that diocesan and Vatican officials will now be free to give summaries of how an internal canonical case was decided, or, if a case warrants it, even to release canonical trial documents themselves.

Of course, the pope’s decree insists that appropriate confidentiality be observed in canonical cases, especially to protect the good name of a person not found guilty of canonical crimes or grave moral offenses, but there seems now to be decidedly more latitude for ecclesiastical officials to make appropriate judgments about what they can reveal, and what they can not.

But there is also a kind of symbolic meaning to the pope’s decree on pontifical secrecy. The pontifical secret is often seen to be nearly as serious and sacrosanct as the confessional seal, and so its role in abuse cases has, by some estimates, become a kind of psychological deterrent, preventing those with concerns about how cases are being handled from raising a red flag, or giving the impression to victims and witnesses that they are not free to speak out about abuse or coercion, and its handling by the Church.

The pontifical secret has also sometimes been invoked, incorrectly, as a reason why ecclesiastical officials have not reported allegations to civil authorities. The pope’s Dec. 17 decree makes clear, in no uncertain terms, that appropriate ecclesiasical confidentiality should not impede reporting to civil authorities, cooperation with civil authorities, or the public manifestation of allegations by alleged victims and witnesses.

The decree seems designed, in short, to say that while some things are appropriately confidential, a commitment to transparency and civil accountability is the order of the day, and ecclesiastical confidentiality should not become a practical, or psychological barrier, to those things.

The pope’s second Dec. 17 decree redefines the Church’s understanding of child pornography. While it was already a serious canonical crime for a cleric to possess child pornography, the pope’s decree establishes that any sexualized depiction of persons under the age of 18 shall be considered child pornography. Until the decree, the universal Church law defined child pornography as “pornographic images of minors under the age of fourteen.”

To many Americans, this decree seems a no-brainer. But while many American reform advocates have called for the change for years, it was often argued that the Church would have difficulty criminalizing the possession of pornography that is legal in some civil states, and that pornography depicting teenagers is in fact legal in some nations. It has also been argued that a person might accidentally possess pornography of an older teenager, whom he understand in fact to be an adult.

The pope’s decree, however, was widely praised for ignoring those arguments, and setting a new ecclesial standard of child pornography, in line with the definitions of most Western states. For this move, the pope is likely to be seen as serious about eradicating as much sexual perversion from the clergy as is possible, and about doing it in a straightforward manner.

In fact, the pope’s Dec. 17 decrees are only the latest in his efforts to address the scourge of clerical sexual abuse and coercion.

The pope’s May letter, Vos estis lux mundi, broadly redefined clerical sexual abuse and coercion, and established clear, and largely well-regarded, procedures for handling both abusive or coercive priests and also bishops accussed of covering up or avoiding allegations of abuse or misconduct.

The Vatican’s February global sexual abuse summit encouraged Church leaders from around the world to set standards for clergy conduct, and made clear the expectation to cooperate with civil authorities and report allegations of abuse and misconduct.

And even the pope’s largely abandoned effort at a tribunal for negligent bishops was an effort to address this issue, established long before the McCarrick scandal brought it to the fore.

For these measures, Pope Francis has mostly gotten high marks for his institutional efforts to address clerical sexual abuse and coercion.

But at the same time, the pope has been criticized for his apparent blind spots: for apparently ignoring, in multiple instances, allegations brought to him personally by alleged victims or by Church officials; for rehabilitating a notorious priest abuser, for finding work at the Vatican for a bishop accused of misconduct; and for being slow, or unwilling, to respond to questions about McCarrick.

To be sure, the pope has acted on personnel. In fact, on Dec. 17, the same day he issued his decrees, Pope Francis accepted the resignation of an apostolic nuncio, or papal diplomat, accused of sexual misconduct. Many observers expect that the resignation paves the way for the nuncio to face criminal charges in France.

Francis has also facilitated the resignation of bishops under fire, like Buffalo’s Bishop Richard Malone, and ordered investigations into other bishops, among them Bishop Michael Bransfield of West Virginia.

Still, the central point of criticism for Pope Francis’ record on abuse focuses not on his policies, but on his own administrative decisions regarding personnel.

For American Catholics, two such decisions are looming.

The bishop of Crookston, Minnesota is the first U.S. bishop to be investigated under the auspices of Vos estis lux mundi. Bishop Michael Hoepnner stands accused of pressuring a diaconal candidate to recant an allegation of abuse, of failing to exercise sufficient oversight of a cleric on a “safety plan,” and of other failures of judgment or administration. Publicly released depositions demonstrate his own admission of failure to follow canonical norms.

Sources in his diocese tell CNA the bishop has almost entirely lost the confidence of his priests, and of lay Catholics in the diocese, as a result of those allegations.

Hoeppner will be in Rome for his quinquennial visit with the pope in January, and American Church watchers will be looking to see whether Hoeppner is, at the point, removed from his office, and if not, what information is provided regarding the results of the investigation of the bishop.

Americans are even more eagerly awaiting the release of a 2018 ordered Vatican investigation into the career, activities, and influence of former cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who sexually abused, coerced, and harassed seminarians, minors, and young priests, according to a Vatican penal process.

The report is an immensely important litmus test of the Church’s commitment to transparency; American Catholics have called for answers on McCarrick for 18 months, and have the expectation that the forthcoming report, rumored to be released in January, will actually provide them with those answers.

Whether or not American Catholics will begin to place trust again in their leaders after a tumultuous year depends a great deal on the candor and thoroughness of the McCarrick report.

While the pope’s record on policy was burnished by his Dec. 17 decrees, for many Catholics, what matters even more is whether they will finally get answers on the network and influence of Theodore McCarrick.