Breaking Out Of The Rut: Moving Forward With Philippine-LAC Economic Relations – Analysis

By FSI

By Rowell G. Casaclang and Karla Mae G. Pabeliña*

The economic relations of the Philippines with Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) could have brighter days. While distance has always been a major impediment, stagnation and a myriad of social uncertainties faced by LAC further threaten an already fragile economic link with the Philippines. How can the Philippines overcome this new hurdle?

LAC in troubled times

LAC so far has seen a significant slump in investment in natural resource industries and deceleration of export due to low demand for exports and low commodity prices. For instance, lower crude oil prices have reduced export earnings and fiscal revenues of regional oil exporters such as Belize, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Venezuela and low prices of copper, iron ore, gold, and soy beans have worsened the terms-of-trade for commodity exporters such as Brazil, Chile, the Dominican Republic, and Peru.

The region is expected to bear the brunt of economic headwinds this year and in 2018. Developed countries such as Brazil and Mexico are facing the highest risks brought about by secular stagnation, a period when economies tend to save more to buffer the ill effects of low inflation and low interest rates. Increased savings leads to decreased investments, which results in reduced growth. LAC has been showing signs that could reinforce long-term growth stagnation: low inflation, low interest rates, rising life expectancy, and falling birth rates.

There is also a high degree of uncertainty due to the growing sociopolitical instability in Venezuela, Colombia, Brazil, and Argentina. Mexico is likewise facing an increased risk of a difficult recovery with the US’ inward-looking policies, rising interest rates, and appreciation of the US dollar. Mexico’s economy will be overshadowed by significant changes to US policy on trade and migration under Pres. Donald Trump. Although abandonment of the North American Free Trade Agreement remains unlikely, softening demand for exports and increased political uncertainty will affect the cost of capital and weigh on consumption and investment in the coming years.

Despite uncertainties, the sociopolitical reforms being instituted by LAC governments are seen to improve the business environment in the region. The shift to pragmatic economic policies – as seen in Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil – from unsustainable social welfare models can potentially shift the economic climate to one that is more conducive for business.

Same old problems, new prospects

LAC is home to about 622 million people.1 Its GDP totals 5.3 trillion (in 2015 current USD), which accounts for 7 percent of total world GDP. Asia’s share of LAC’s trade has risen in the past several years, amounting to 21 percent in 2010. In contrast, LAC’s share to total Asia’s trade has been stagnant for almost a century (peaking to merely 4.4 percent by 2010).

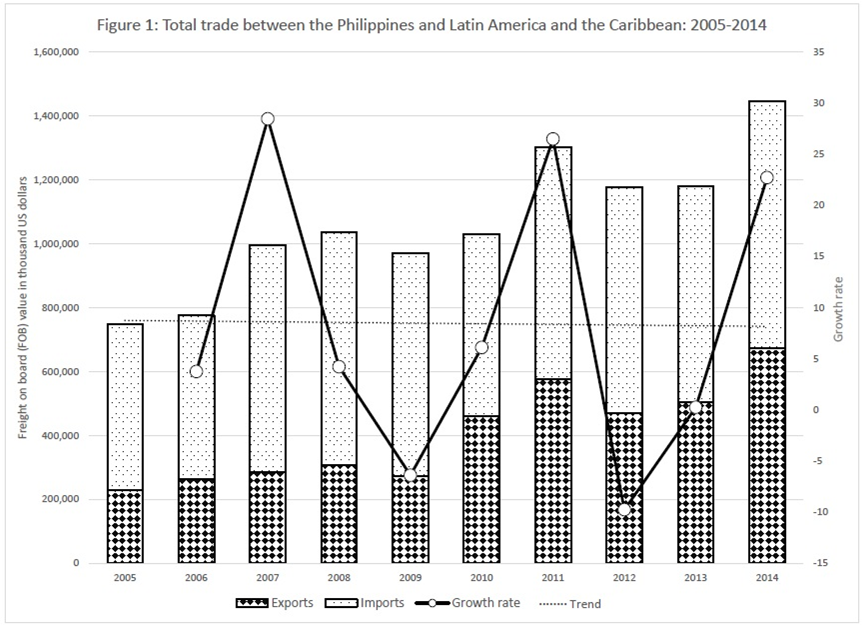

In the case of the Philippines, trade with LAC has not shown a positive trajectory in the past decade. In the period from 2005 to 2014, the average annual growth rate of Philippines’ trade with LAC was only 8.4 percent. LAC’s share of Philippines’ imports and exports was just 1.1 percent in 2014.2 In addition, there is no particular policy guiding Philippines’ economic relations with LAC. Various consultative meetings have been held to improve trade and investment and to examine possible cooperation in mining, energy, education, logistics, and consumer retails, most of which, however, remain in the pipeline.

Among the LAC group3, the Philippines’ most important trading partners (based on share of PH-LAC bilateral trade vis-à-vis total PH trade) during said period were Brazil (33 percent), Argentina (32.6 percent), and Mexico (26.4 percent). While no trade facilitation measures (e.g., free trade agreements, among others) were in place, the enormous markets of Brazil and Mexico, where populations reached 207 million and 127 million in 2015, respectively, are deemed to be the primary reason why terms of trade with these countries were high. Bilateral trade with Brazil comprised mainly of imports (68 percent), especially of metallic ores. In the same period, Mexico was the top export destination in the LAC region (55.2 percent of total exports to LAC) while Argentina was the lead importer (46.7 percent of total imports from LAC).

The modest performance of PH-LAC trade can be attributed to several factors, among them, geographical distance, which generates high transport costs, and trade barriers including tariff and nontariff types. Argentina, for instance, imposed strict import controls starting February 2012 as a response to falling trade surplus and as a way to protect its international reserves and local industries. This import policy has proven difficult for Argentina’s trading partners, including the Philippines, to expand entry of their products. Balance of trade between the Philippines and Argentina heavily favors the latter (about 89 percent were imports from Argentina).

The fragmented nature of integration in LAC with the market-led Pacific Alliance (Peru, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico) and the MERCOSUR or Common Market of the South (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay) poses another challenge to strengthening collaboration. The differences between these two blocs reflect the deep-rooted divide in economic policy and orientation among the LAC countries. Pacific Alliance is committed to open trade and free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor while MERCOSUR imposes significantly higher tariff and non-tariff barriers. Both groupings are nonetheless taking steps to bridge the hemispheric divide towards a convergence of their policies.

Better prospects in the horizon

There is substantial opportunity to strengthen trade and investment with LAC through existing economic frameworks (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, Pacific Alliance, and Forum for East Asia-Latin America Cooperation) and forthcoming bilateral economic arrangements which include the Bilateral Investment Treaty with Mexico, Joint Economic Cooperation with Peru, and a free trade agreement with Chile. The Philippines occupies a unique position as LAC’s gateway to Southeast Asia, with its common Hispanic heritage as an advantage over neighboring states.

Current limitations and challenges of trading with LAC notwithstanding, LAC remains a huge market that offers a wealth of opportunities for the Philippines. Complementary industries may create basis for further cooperation: LAC provides agricultural, resource-based products, and services while the Philippines exports electronic components/supplies, machinery, and equipment. As it revs up its manufacturing industries, the Philippines would benefit from LAC primary resources, which include hydrocarbon and metals.

However, the period of stagnant growth in LAC creates a gamut of possible policy shifts among LAC countries. In the midst of a declining export demand and plunging commodity prices, LAC countries are predisposed to consider diversifying their economies in an effort to improve productivity and broaden export base. As this move is seen as beneficial to LAC economies, it can generate competition with trading partners and in effect hurt prospects of expanding trade complementarities. Otherwise, LAC countries could revert to protectionist policies to induce growth. As Argentina is currently doing, encouraging exports while keeping imports at bay will only exacerbate the difficulties arising from the present challenges faced by LAC’s trading partners.

Thus, the looming secular stagnation felt in some LAC countries is a risk that the Philippines must keep an eye on. Further in-depth studies must be made on a per country basis to ascertain the implications of long-term growth stagnation and how it will affect the conduct of future bilateral economic relations.

In addition, despite the highly volatile sociopolitical climate in Latin America, pragmatic reforms being instituted by its governments may shift the business climate. It is therefore important for the Philippines to continue efforts in securing bilateral economic arrangements that will promote and sustain long-term and viable trade and investment flows. Promotion of trade and investment through existing multilateral and regional arrangements should also be augmented.

Amidst the gloomy picture that LAC paints, the region offers numerous opportunities for the Philippines. It remains an ironic reality that the shared Hispanic heritage and deep cultural ties are not harnessed to further economic engagements.

*About the authors:

Rowell G. Casaclang is a Foreign Affairs Research Specialist with the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Casaclang can be reached at [email protected].

Karla Mae G. Pabeliña is a Foreign Affairs Research Specialist with the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies of the Foreign Service Institute. Ms. Pabeliña can be reached at [email protected].

Source:

This article was published by FSI. CIRSS Commentaries is a regular short publication of the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies (CIRSS) of the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) focusing on the latest regional and global developments and issues. The views expressed in this publication are of the authors alone and do not reflect the official position of the Foreign Service Institute, the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Government of the Philippines.

Endnotes:

1 Populations in 2015 for the 20 sovereign states in LAC region: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. World Bank estimate: 633 million.

2 Based on Philippine Statistics Authority’s Foreign Trade Statistics 2005-2014. LAC’s share to Philippines’s total trade averaged only 1.0 percent in the ten-year period.

3 Percentages represent share to total trade between the Philippines and LAC region in the period 2005-2014. Due to data unavailability, the LAC group comprised only Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela.