JCPOA’s First Anniversary: Significance And Future Challenges – Analysis

By IPCS

By Manpreet Sethi*

Provocations, sobered by abundant caution, were the hallmark of the first year of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), simply called the Iran deal. For now, the supporters of the agreement can breathe easy that it has lived to celebrate its first anniversary. Given that it took the international community 13 long years of difficult negotiations peppered with allegations and counter-allegations to resolve the ‘Iranian nuclear issue’, it is heartening that all parties managed to stay the course despite distractions.

President Obama, who provided dogged support during the negotiations in face of strong opposition from the Republicans and even some influential Democrats, besides a very vocal Israel, displayed his commitment to the deal in the last 12 months. President Rouhani too showed a personal conviction in its implementation. Luckily, he has also had the backing of the Supreme Leader. Meanwhile, proactive diplomacy by the EU, China’s economic interest in mainstreaming Iran, and Russian desire to be seen as playing a constructive role at the international high table have also been equally critical in making the JCPOA endure.

The Iran deal is an interesting agreement that has been subject to many interpretations. Western countries value it for its ability to remove the near-time risk of Iran’s nuclear weapons breakout. Iran considers it a tool to remove the sanctions pressure that was adversely impacting its economy, besides using it also to showcase the country’s strength to stand up to major powers by having managed to retain the right to enrichment, even if to low levels. Thus, the country vindicated its pride and position.

Over the last year, the JCPOA has provided a useful framework for Iran to resume meaningful relations with the international community. The most immediate benefits have been in the upsurge in its oil exports. By April 2016, Iran had begun exporting oil to the tune of 1.7 million barrels per day (mpbd), up from 700,000 mbpd during the period of the sanctions. Meanwhile some of the formerly blacklisted Iranian banks have reconnected to SWIFT and inflation is down to 12 per cent compared to 40 per cent in mid-2013. However, the quick economic gains that the public was expecting are yet to materialise, leading to impatience and disenchantment. This is partly because Iran itself has yet to get its institutions and entrepreneurial skills ready to exploit the opening. Besides an opaque banking system, it also suffers from corruption, an inflexible labour market, traditional dominance of the public sector, and multiple political power centres often in conflict with each other.

While resolution of the structural issues will take time, the sense of disappointment in public given the slow trickledown effect could be utilised by deal naysayers, particularly the hardliners in the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Council (IRGC), to fan nationalism and hostility. It may be recalled that the IRGC had described the deal as ‘nuclear sedition’, and tried to scuttle it, including by undertaking missile launches in March. More such attempts could put Iran’s engagement with the world again under a cloud. For the moment though, President Rouhani seems relatively better placed after the recent elections in March 2016. The vote was seen as a sort of a referendum on the nuclear agreement, indicating a desire of the Iranian people to support leaders who could get them out of political and economic isolation.

Meanwhile, there are chances of things going wrong at the US end particularly as the domestic political situation heats up in the run up to the presidential elections later this year. Already, not many Americans, in the Congress or out of it, have solidly put their weight behind the deal. A Gallup poll in mid-Feb 2016 showed 57 per cent of the Americans as being opposed to the agreement and only 30 per cent approving it. President Obama is doing his best to kill any legislative action that could jeopardise the JCPOA, but its future would seriously depend on the next occupant of the White House.

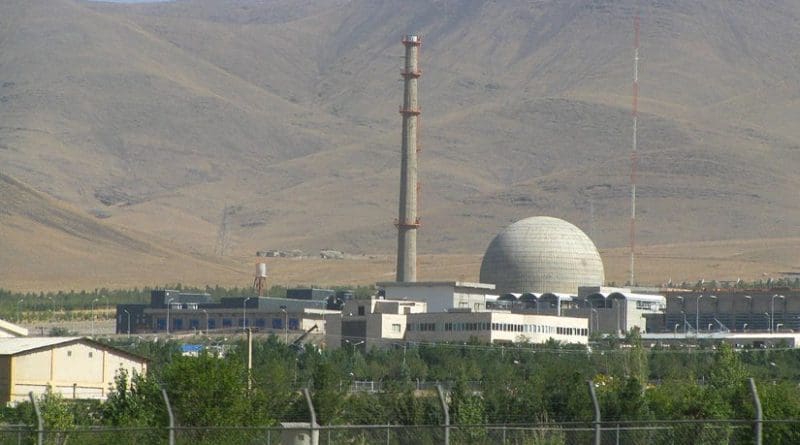

Given the volatility in Iran and the US, other stakeholders such as the EU, China, and Russia will have to remain constructively engaged with the implementation process and watch out for any drastic action by either Iran or the US that could rock the JCPOA. For now, Russia has already started receiving enriched uranium that Iran must remove from its territory and China has started work on re-designing the Arak reactor. Slowly, as all sides build confidence in each other and as benefits flow into Iran start to make a difference, the deal would acquire surer footing. There would develop a vested interest of each to avoid violation of the agreement.

The next helpful step in this direction would now be to initiate measures that could help resolve regional issues to make all players more secure. Of particular relevance in this context is the need to find a way of establishing a Middle East WMD Free Zone. This has been a long-standing objective of the NPT. In fact the NPT RevCon 1995 had secured an unconditional and indefinite extension of the treaty on the promise of resolving the Middle East nuclear conundrum, particularly with reference to Israel’s undeclared but well-known nuclear weapons capability. The Iranian nuclear issue would receive a more secure sense of resolution if regional security issues could be addressed through the elimination of all nuclear weapons from the region. The task will certainly not be easy. In fact, even a conference of the regional powers to discuss the issues under the aegis of the special authority appointed in the form of an ambassador from Finland in 2010 has not yet been possible. Nevertheless, work must be started on this next step after the JCPOA. It will be a long journey but one that must get started.

* Manpreet Sethi

ICSSR Senior Fellow affiliated with the Centre for Air Power Studies (CAPS)