Catalonia’s Independence Bid: How Did We Get Here? What Is The European Dimension? What Next? – Analysis

1. Some background information on Catalonia as part of Spain

- As in Canada and Belgium (and, to a certain extent, the UK), centre-periphery tensions constitute a permanent feature of Spain’s political landscape.

- Spain undertook early and effective state-building in the 15th-18th centuries but a late and more troubled nation-building process in the 19th-20th centuries, with strong regional identities in competition, particularly in Catalonia and the Basque Country. They were never ‘independent’ in the modern sense, being parts of composite monarchies, but have some historically distinctive traits.

- Nevertheless, Spain is one of the very few cases in Europe in which national integrity has been successfully preserved: not a single territorial change has occurred in the past 200 years (colonial possessions aside, which were not an integral part of Spain)

- Despite its initially conservative bias, peripheral nationalism became partly associated with freedom and the fight against central authoritarianism. Regional self-government was linked to democracy: devolution to Catalonia in all the democratic periods (1873-74, 1914-23 and 1931-39) and its suppression under the dictatorial regimes of Primo de Rivera (1923-31) and Franco (1939-76).

- After its transition to democracy in the late 1970s, Spain can be considered a federation in all but name, with 17 autonomous communities having extensive devolved powers, guaranteed by the Constitutional Court.

- Although the 1978 Spanish Constitution states that sovereignty resides with the Spanish people as a whole, it also specifies that regions and ‘nationalities’ have a right to political autonomy.

- Catalonia today is wealthier than the Spanish and EU average, and enjoys more powers than almost any other region in Europe, including the protection of the Catalan language.

- Nationalism in Catalonia was linked to both the peasantry and part of the bourgeoisie. The region simultaneously experienced industrialisation (it bordered France, with a weak Spanish state but a large internal market) and a so-called ‘cultural renaissance’.

- During the 20th century, Catalan economic growth attracted large-scale immigration from all over Spain.

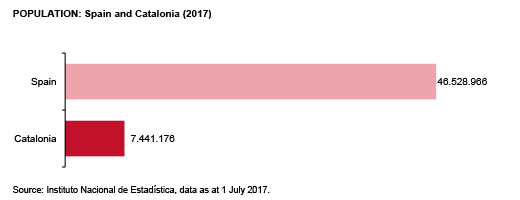

- While Catalans only account for around 16 % of Spain’s population, the region is wealthy and accounts for 19% of GDP

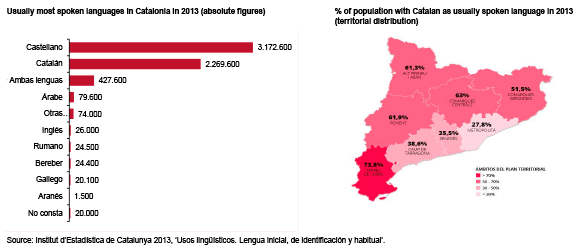

Contrary to a widespread perception, the Castilian (Spanish) language spoken more in everyday use than Catalan. In Barcelona and other urban areas, 75% of the population usually speak Spanish, while Catalan is employed to a greater extent in the countryside. A full 99% of Catalans can understand Spanish and 95% are familiar with Catalan.

- The region enjoys a high degree of self-government regulated by the 2006 Catalan Statute. Despite the Constitutional Court ruling in 2010 that certain articles were unconstitutional (dealing with an autonomous judiciary and self-recognition as a ‘nation’), Catalonia has extensive powers in:

- Civil law, police, culture, language, education, health care, agriculture, fisheries, water, industry, trade affairs, consumer affairs, savings banks, sports, historic heritage, environment, research, local government, tourism, transport, media and a wide range of other issues.

- Catalonia also has its own tax collection system, although funding –and social security benefits– is mainly controlled by the central government. Although foreign policy is an exclusive power of the central government, the regional government has its own external action and a strong network of offices abroad.

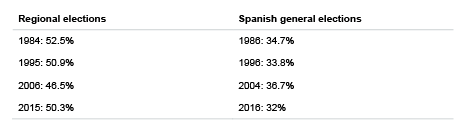

- The Catalan nationalist parties’ share of the vote has remained fairly stable:

2. Factors explaining Catalonia’s bid for independence

- Until the mid-2000s Catalan society was roughly split into three equal parts:

a) A group comprising the rural population and the urban middle and upper classes, who feel that Catalonia is a stand-alone nation due to its distinctive language and culture and greater prosperity than the rest of Spain.

b) A sociologically less cohesive group made up of the descendants of immigrants from other Spanish regions who retain a predominantly Spanish identity and have Castilian as their mother tongue.

c) Those with a shared Spanish-Catalan identity who tend to be truly bilingual.

- This mixed and complex sociological structure resulted in the dominance in Catalonia of two big moderate parties: the Catalan branch of the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE-PSC) to the centre-left and the regionalist Convergencia i Unió (CiU) to the centre-right, which was in office for most of the period 1980-2010.

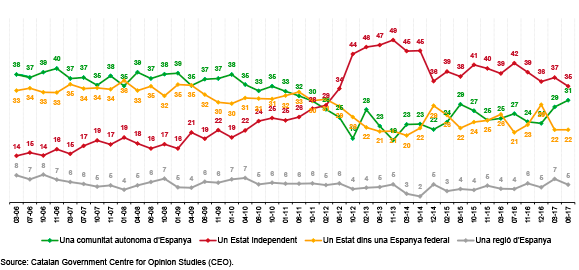

- Before 2010, it was unusual for more than 20% of Catalans to support independence.

- The political status quo changed around 2010 for a number of reasons, some of them resulting from long-term developments and some due to short-term factors.

-

External long-term factors:

a) Globalisation and EU integration can encourage secession: free trade and international governance mean that states no longer need to be big to exploit economies of scale. The economic and political risks of independence are lower in a supranational area such as the EU.

-

Internal long-term factors:

a) Catalonia’s own nation-building after the 1980s (regional education, regional television).

b) Tension with the Spanish national project after 1978, despite moderate nationalists contributing to Spanish governance from 1977 to 2012: a feeling of mutual distrust.

-

External short-term factors:

a) In 2012 the Scottish National Party (SNP) negotiated a binding referendum for Scottish independence, setting out a plausible and respectable precedent for democratic secession within Europe.

b) Stability measures linked to the Eurozone crisis –EU-led austerity and the central control of regional finances– encouraged populist messages of fiscal rebellion (similarly to UKIP and Lega Nord).

-

Internal short-term factors:

a) From 2008 onwards, Spain (including Catalonia) suffered a deep economic, social and political crisis.

b) The Spanish Constitutional Court, following an appeal by the centre-right PP partially outlawed the 2006 Catalan Statute in 2010.

c) The PP replaced the Socialists in power in Madrid in late 2011, giving rise to fears of a move towards re-centralisation.

d) Nationalist elite polarisation, outbidding competition and the rise of secessionism in 2012.

- Support for secessionism reached a peak of 49% in 2010, subsequently declining. The most recent survey by the Catalan government’s Centre for Opinion Studies (CEO), conducted in July 2017, shows that only a minority of Catalans (35%) support independence (see Graph overleaf).

- In recent surveys, 76% of Catalans actually identified with Spain. Support for Catalan secession is far from overwhelming.

- QUESTION IN THE POLL: “Catalonia should…?”: be an independent state (red), maintain the status quo (green), acquire a new status and greater powers within a federal Spain (yellow) or be a region (grey)

3. Secession and EU membership

- The existence of the EU itself may be an encouragement to secession: ‘Independence in Europe’ is the slogan of Scotland’s SNP and ‘Catalonia, a new state in Europe’ was the slogan of the huge September 2012 demonstration in Barcelona, which marked the beginning of the current independence process.

- However, since Catalans and Scots wish to remain in the EU, its rigid rules on enlargement are an obstacle:

‘When a part of the territory of a Member State ceases to be a part of the state, eg because that territory becomes an independent state, the treaties will no longer apply to that territory’ (EC President R. Prodi, 2004).

‘A new independent state would, by the fact of its independence, become a third country with respect to the EU and the Treaties would no longer apply on its territory’ (Letter to the UK House of Lords from EC President J.M. Durão Barroso, 2012).

- Simultaneous or, at least, ‘fast track’ accession has been proposed:

- Negotiations on membership can take place during the period between a ‘yes’ referendum and the planned date of independence (no need to leave and apply for readmission).

- The EU would adopt a simplified procedure for accession negotiations, not the traditional procedure.

- In any case, such an agreement would depend on political will and be subject to unanimous ratification by all member states. It is ‘wishful thinking’, since consensus is unlikely for Scotland and impossible for Catalonia.

4. Why are Catalonia and Scotland different? (1/3)

- An agreed process in Scotland vs unilateralism in Catalonia. The Catalan case involves flouting the rule of law, both in Spanish and European terms: ‘The Union shall respect their essential state functions, including ensuring the territorial integrity of the state…’ (article 4.2 Treaty).

- There are important political differences:

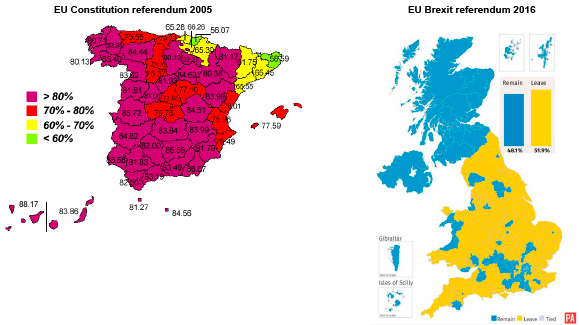

- Pro-Europeanism in Spain vs Brexit in the UK:

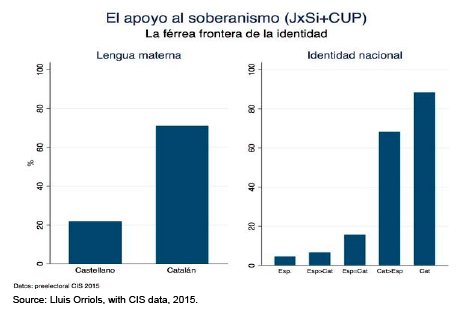

- Scottish nationhood within a multinational UK vs potential intergroup conflict according to identity/language in Catalonia, where two nation-building projects co-exist.

- The ‘Revolt of the Rich’: Catalan nationalism can be perceived as selfish and rejecting solidarity while that is not the case with Scotland.

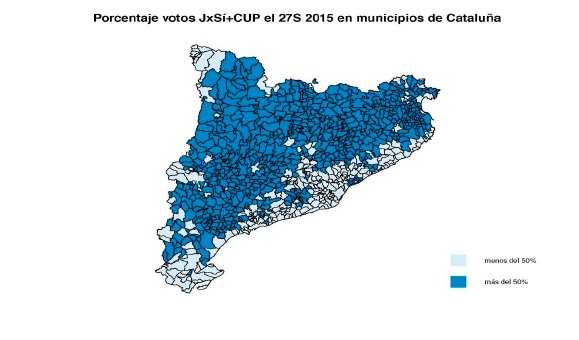

- There is a sharp division between the rural, with a majority in favour of secession), and the urban, with a majority against:

5. Attempts to ‘internationalise the conflict’

- Internationalising the secession process has become a key factor in the Catalan strategy. As the Spanish Parliament and Constitutional Court insist the region has no right to self-determination, the only alternative is to seek external actors to put pressure on Madrid for a referendum.

- The underlying logic is sometimes idealistic: despite the dominant paradigm of territorial integrity, the EU and the international community should support the ‘Catalan democratic mandate’. But it also appeals to realism: foreign governments and financial markets cannot afford a chaotic default given Spain’s public-debt burden and the importance of the Catalan economy.

- The Catalan bid has so far received no foreign support: Merkel, Hollande, Obama, Cameron, Macron, Trump, Juncker, Tusk and all international leaders except Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro explicitly support a united Spain and the rule of law.

- A change in the position of international leaders is unlikely given their strong reluctance to support or pragmatically accept independence as secessionist parties have always failed to win a clear majority and polls show that Catalans remain wary of independence (not to mention a unilateral process).

- Catalan public opinion (around 70%) supports a mutually-agreed referendum, although it is debatable whether it would be an adequate instrument to solve such a complex controversy.

- Referendums are not suited to highly divided societies. Places like Belgium and Northern Ireland, for instance —where cleavages are based on entrenched identity, linguistic or religious divisions— hardly ever resort to them. When they do, the experience has been traumatic, both exposing and deepening sectarian hostility.

- Given the strong correlation between language and political preferences on the issue of Catalan independence, a referendum may become a divisive zero-sum mechanism, in which a small —and probably unstable— majority imposes its preferences in a manner not easily reversible. Divided societies need power-sharing strategies and consociational arrangements to defuse conflicts.

- Some international media and segments of Spanish and European public opinion are in favour of a referendum but such a debate does not imply they support unilateral action.

- Third-party states will not challenge the interpretation by the state concerned of its own national Constitution (as it is a merely internal affair), particularly in the case of a UDI (since there is no case for remedial secession).

6. What next?

- According to the most recent polls, when Catalans are asked a binary question (‘yes’ or ‘no’ to secession), a majority are against but society is riven down the middle:

- Such a divisive stalemate could be avoided by devising a new form of accommodation within Spain.

- Without external support, with Catalans deeply divided and with no chance of effective territorial control by the Catalan government, Spain is not on the point of disintegration but the territorial crisis is here to stay.

- Without Catalonia there would be no Spain since the Spanish national project would be voided, while Scotland is seen in the UK as ultimately more dispensable.

- Although the case for a Catalan secession is weak, it is obvious that some kind of political compromise will be required to encourage 50% of the Catalan population to be comfortable within the Spanish state.

- Recent events have generated much uncertainty, including:

The unofficial or illegal referendum held on 1 October, with a 40% turnout and a widely criticised over-reaction by the National Police and Civil Guard.

A situation of high social unrest and the political mobilisation of the pro-Spanish segment of Catalan society.

The exit of many of the most important Catalan companies, generating doubts in the fragile nationalist coalition.

The suspension of the unilateral declaration of independence in the regional parliament.

The Spanish government’s request to the Catalan government to clarify the situation regarding the declaration of independence, which may lead to the partial suspension of self-government (federal coercion).

The possibility of further mobilisations in the streets (the Catalan Maidan?), which cannot be ruled out.

- Nevertheless, these events also provide an important window of opportunity following the announcement by the PP and the PSOE of the possibility of constitutional reform.

This article was published by the Elcano Royal Institute.