Using Science Diplomacy In The South China Sea – OpEd

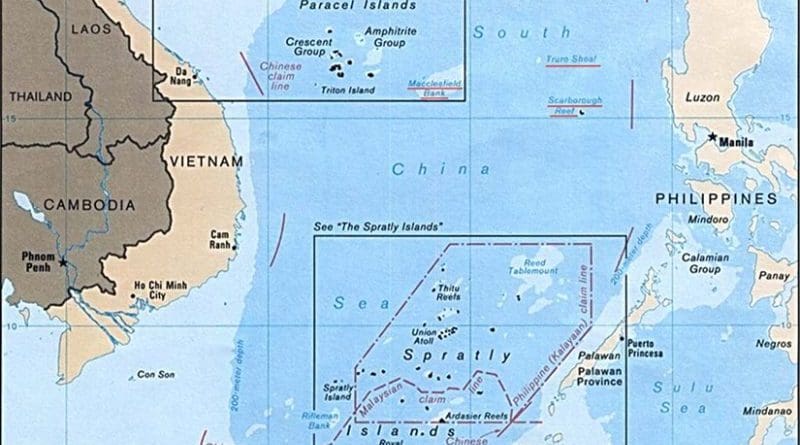

Despite White House efforts to deny well-established climate change reports and U.S. withdrawal from the 2015 Paris Climate Accord, most might question the wisdom of laying down a science — led peace-building plan in the contested South China Sea disputes. Yet science may prove to be the linchpin for bringing about cooperation rather than competition not only among the claimant nations in the region but also between Washington and Beijing. While President Trump’s recent offer to Vietnam’s President Tran Dai Quang to mediate the complex and challenging disputes over access to fish stocks, conservation of biodiversity and sovereignty claims caught many observers by surprise, it should not have.

The stakes are getting higher in the turbulent South China Sea, not only because of Beijing’s militarization of reclaimed islands but also the prospects of a fisheries collapse. This should weigh heavily on all claimant nations and especially the United States. Challenges around food security and renewable fish resources are fast becoming a hardscrabble reality for more than fishermen. In 2014, the Center for Biological Diversity warned that it could be a scary future, indeed, with as many as 30-50 percent of all species possibly headed toward extinction by mid-century.

It’s not too late for the U.S. to take the scientific high ground and renew the legacy of science diplomacy. After all, science initiatives are more widely accepted as efforts to solve global issues requiring contributions from all parties even if they have been dealt a bad hand elsewhere. On Nov. 3, the White House signed off on a report attributing climate change and global warming to humanity. The report is in direct contradiction to the president’s action pulling the U.S. out of the Paris accord on climate change earlier this year.

Enter science diplomacy, defined as the role of science being used to inform foreign policy decisions, promoting international scientific collaborations, and establishing scientific cooperation to ease tensions between nations.

During the Cold War, scientific cooperation was used to build bridges of cooperation and trust, and it’s now time that the South China Sea becomes a sea that binds rather than divides.

There are strong ties among scientists across Southeast Asia and China, due in part to a series of international scientific projects, conferences and training workshops associated with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s South China Sea Fisheries Development and Coordination program.

Marine scientists in the Philippines and Vietnam are reviving conversations about the Joint Oceanographic Marine Scientific Research Expeditions (JOMSRE) last conducted in 2005 and organized between the Philippine Maritime and Ocean Affairs Center and the Vietnamese Institute of Oceanography.

These measures are essential in the face of rampant overfishing and coral reef degradation occurring across the South China Sea, in part because of the conflicting territorial claims have made ecological analyses and management actions difficult.

With the imminent threat associated with North Korea’s nuclear tests, Mr. Trump’s Asia advisers must come up with new narratives on how to convince China to rein in this clear and present danger. However, President Xi Jinping’s recently expanded role makes it less likely that the U.S. will secure any further commitments from Beijing to address North Korea.

Michael Crosby, president and CEO of Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Fla., believes the U.S. could dramatically improve international relations through marine science partnerships, and he understands the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) contains specific articles that apply to marine science and technology.

“A renewal of JOMSRE would be quite positive, although the changing political dynamics related to the Spratlys and other islands and reefs in the region over the last several years will likely create a bit more challenging environment for an international research survey,” Mr. Crosby said in an email.

In the early 1990s, University of Miami marine biologist John McManus called for a marine peace park in the hotly contested Spratlys.

“Vietnam, a claimant nation, already has marine reserves, so this involves extending this practice to the Spratly area. It is usually difficult to institute conservative harvest and protection practices when there is the threat of competition from outsiders. Vietnam stands to lose a great deal if the current situation continues and results in a general decline in fisheries across the South China Sea,” claims Mr. McManus.

Although the U.S. is not a signatory to UNCLOS, Washington can recommend that sovereignty claims be set aside in treaties implementing freezes on claims and claim-supportive activities, as has been done in the Antarctic. These and other natural resource management tools could be used far more effectively to secure fisheries and biodiversity, and also promote sustainable tourism.

While President Trump has made it abundantly clear that he fully intends to protect and promote the U.S. fossil-fuel industry, he may find this new collaborative brand of science diplomacy works well in Asia.

• James Borton is a regular contributor to Asia Sentinel and a nonresident fellow at the Stimson Center in Washington. He is the editor of “Islands and Rocks in the South China Sea: Post Hague Ruling” and “The South China Sea: Challenges and Promises.” This article appeared at The Washington Times.