Commitment To Democracy Must Remain Independent Of Geopolitics – Analysis

By Maiko Ichihara*

South and Southeast Asia have experienced a sharp decline in liberal democracy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Under the pretext of combating COVID-19, the Philippines and Thailand have suppressed freedom of speech, while Indonesia has concentrated power in the hands of government. India has promoted a COVID-19 tracking application that violates personal privacy while the military coup in Myanmar subverted the democratic elections of November 2020.

With democracy in retreat across Asia, the future of the liberal international order is at stake.

The momentum to curb this crisis of liberal democracy has come not from Asia but from the United States. The Biden administration’s explicit recognition of the importance of defending and revitalising democracy around the world – particularly after four years of democratic backsliding at home under Donald Trump – is a norm-defending move. The present crisis of democracy threatens to put an end to the cascade of democratic norms that started in the mid-1970s. The renewed commitment to democratic norms in the United States — a symbol of democracy — is important.

The Biden administration has taken concrete actions to protect democratic values, including by issuing national strategies on gender equality, regaining its seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council and imposing sanctions for cases of serious human rights violations in Belarus, Myanmar, North Korea and China.

Despite Biden’s efforts, it has become clear that defending and revitalising democracy is a more challenging task than anticipated. One barrier to this has been the priority placed on security policies.

A central theme of the Biden administration has been ‘democracy versus autocracy’, with US–China confrontation at its core. Unlike Trump who viewed the US–China rivalry primarily as a zero-sum trade balance sheet, Biden has revisited the China issue in response to growing security concerns. Democracy is now a banner for strengthening alliance networks against the China threat. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or the Quad, and the AUKUS nuclear pact are important manifestations of this in current US foreign policy.

Associating US–China competition with the issue of political regime type has rendered democracy as an ideological tool in diplomacy. People suspect that democracy is a void concept used arbitrarily by the US.

Given that democracy is a universal value, the defence of democracy should be separated from US–China confrontation and addressed both domestically and internationally. This is a particularly important point for Southeast Asian countries that have close economic ties with China while also managing territorial disputes with the country. They do not wish to be drawn into US–China confrontation and do not want to be forced to choose between sides.

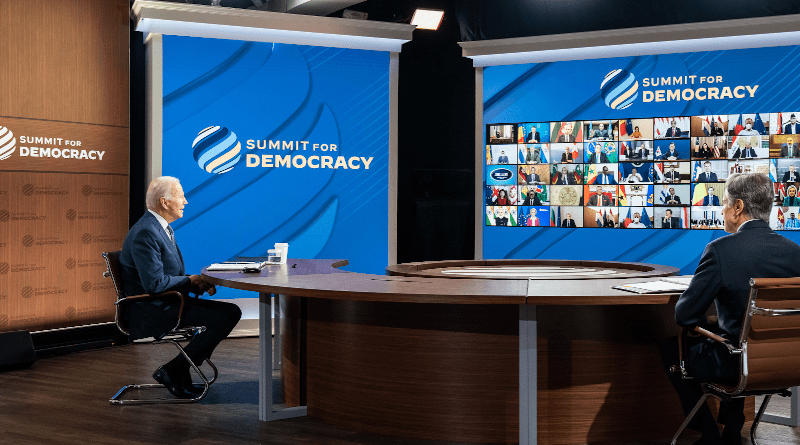

On 9–10 December 2021, the Summit for Democracy was held bringing together countries from across Asia and the rest of the world. The significance of this summit will depend on how well a commitment to democratic values and norms emerges in the coming year of action.

At the summit, participants proposed measures to strengthen their own democracies and the situation abroad, regardless of whether they are in a geopolitical position to be useful in the competition against China. Materialisation of these proposals is at stake until the second summit. For Asia, a framework that regional countries can use to defend democratic governance should be developed. Although there is a sense of caution about the umbrella terms of human rights and democracy, Asian countries have accepted norms related to good governance, such as transparency, accountability and anti-corruption. These norms are indispensable in defending and promoting democratic governance.

The media must also play a role in helping prevent the public discussion following the Summit for Democracy from overt politicisation. Immediately after the White House released the participant list for the summit, the media focused on the invitation of Taiwan. While it is undeniably eye-catching, this centred some discussion around the summit on US–China rivalry. Instead, the media should have covered the summit comprehensively, including what it is trying to accomplish, what the big-tent approach of inviting 111 countries and regions means and how the follow-up process should be designed.

The centre of gravity in international politics lies in Asia. Whether Asia can protect and revive liberal democracy will be critical in determining the future of the liberal international order in the entire world.

*About the author: Maiko Ichihara is an Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Law and the School of International and Public Policy, Hitotsubashi University.

Source: This article was published by East Asia Forum