What Is Hampering Syria’s Referral To International Criminal Court? – OpEd

The narrative surrounding the role of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in Syria is filled with despair and hopelessness. This is primarily due to a realization that despite overwhelming evidence of War Crimes in the country the situation cannot be referred to the ICC by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) given the existing geo-political realities pertaining to such a referral.

To contextualize the issue, the ICC can assume jurisdiction of a situation if either of the following three conditions materialize, firstly, the conflict pertains to a country that is a party of the Rome Statue (the statute establishing the ICC), secondly, the person to be prosecuted is a citizen of a State Party and lastly, the UNSC by a majority deciding to refer the case to the Court without a veto exercised by any of the P5 members.

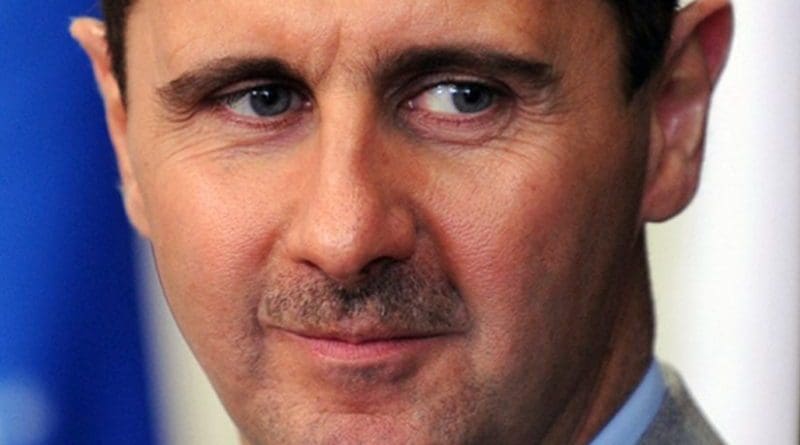

Syria, the theater of the conflict is not a State Party to the Rome Statue, President Bashar Al Assad and a majority of the major actors (including non-state ones) involved in the conflict are not citizens of a State Party and lastly the UNSC due to strategic differences has no immediate plans to refer the case to the Court and has rejected such attempts in the past. However, it is submitted that calls for ICC’s intervention in Syria even with the full backing of the UNSC is premature without effectively addressing the following two issues requiring clarity in International Law.

Issue 1: Can an Incumbent Head of State and other top officials be arrested and Prosecuted for War Crimes as viewed in the context of Sudanese President Omar Al Bashir’s precedent?

As stated earlier, there appears to be little doubt that War Crimes have been committed in Syria. These crimes including but not limited to indiscriminate and reckless attack on civilians, bombing of residential areas, use of suspected chemical weapons, attacks on hospitals and other civil facilities and use of starvation as a method of in Syria have been well documented.

Most if not all of these grave violations are attributable to the Syrian Government headed by President Assad. However, it’s not clear how the President and other High level functionaries can be held accountable in light of existing international law principles. The referral of Sudan to the ICC by the UNSC Resolution 1593 in 2005 is significant in this context. Sudan’s referral to the ICC was unprecedented on five major counts.

Firstly, it was the first time that the UNSC unanimously voted to refer a situation to the ICC. Secondly, the subject of the arrest warrants subsequently issued by the ICC on the basis of the referral was the sitting President of the Country. Thirdly, Sudan was not a party to the Rome Statute and was forcibly referred to the court despite its staunch opposition. Fourthly, the wordings of the Resolution imposed seemingly binding obligations on other State Parties and lesser requirement on non-state parties including a binding obligation of Sudan itself. Fifthly, the subject of the warrant continues to be the President despite international calls for his arrest and ICC judgments faulting different State Parties in not fulfilling their obligation to the ICC by not arresting him.

While Article 27 of the ICC statute states that official capacity is irrelevant for prosecuting an individual, Article 98 stipulates that states in their obligation to the ICC cannot be compelled to violate their obligations under Customary international law pertaining to Sovereign immunity. The ICJ in the Arrest Warrant Case in 2000 asserted that high office holders of a country have customary international law immunity from arrest warrants issued by other countries even for War Crimes1.

Thus there appears to be a conflict between Articles 27 and 98 as regards the power of the ICC to indict and prosecute a Sovereign head of state. If read harmoniously, the best conclusion that can be drawn is since ICC is a treaty creation its obligations ought to prevail over customary obligations, meaning thereby that ICC signatories have an obligation to arrest a head of State since they implicitly agree to forfeit claims of Sovereign immunity while accepting the jurisdiction of the ICC.

However, since neither Sudan which was forcefully referred to the ICC by the UNSC nor Syria which has so far escaped referral to the ICC are members of the ICC both can claim immunity for their respective Presidents and officials in light of this scenario. Strangely enough a binding obligation under UNSC Resolution 1593 to co-operate with the ICC was put on Sudan- a Non State Party (despite Basheer being the head of state). Thus till a clarity on sovereign immunity for Presidents and other highly placed officials for War Crimes evokes an objective answer in International law contextualized with Basheer’s case it is preposterous to talk of hauling Syrian officials including President Assad to the ICC.

Issue 2: Can a non-state party have obligations towards the ICC?

With 124 members, around one-third of the international community refuses to accept the mandate of the ICC. Recent withdrawals from the ICC by certain African countries have stirred a debate on ICC’s institutional bias if not dented the credibility of the institution. Article 18 of the Vienna Convention on the law of Treaties, 1969 impose an obligation, albeit vague, that states should refrain from acts that defeat the objects and purposes of a Treaty but this obligation is only on signatories.

According to Article 34, a treaty cannot create obligations for third states without their consent. The Rome Statue, in agreement with this philosophy obliges only member states with compulsory obligations. Even Resolution 1593 explicitly exempts non-state parties from obligations arising under the Resolution. Even if it’s argued that Sudan’s referral was under Chapter VII of the UN Charter and thus binding on all member states including Sudan (despite the express exemption of Non-state parties from obligations) it doesn’t explain the refusal/inability of many countries (including State Parties like Malawi, Chad, DRC and South Africa) to arrest Basheer during his visits and stopovers there amidst the curious requirement of Sudan being obliged to arrest Basheer despite his continued status as President of the country.

In pursuance to this breach of obligation, the ICC in a total of 11 findings held nations to be in “breach of obligation to co-operate” under Article 87 (7) of the Statute which requires compulsory co-operation from State Parties. These cases, post judgment were referred to the UNSC and ICC’s Assembly of State Parties (ASP) for further action which has not evoked a sufficiently strong response from the UNSC.

Thus where it’s increasingly getting difficult to compel a State party to ensure compliance with obligations arising under the Sudanese situation one wonders the utility of calling for a Syrian UNSC referral without broader institutional debate on existing scenarios.

However, there has been an argument that non-signatories to the ICC may have an obligation towards its mandate by virtue of Common Article 1 of the Geneva Conventions, 1949 which imposes an important obligation “to respect and ensure respect” for international humanitarian law (IHL) obligations. The Geneva Conventions and their mandate today form an integral component of Customary International Law and are universally binding. Nations on their part have universally accepted and ratified the document.

While the nature of the conflict in Syria smacks of contempt towards the Geneva Convention, it is doubtful whether the compulsory obligation of the international community “to respect and ensure respect” to IHL under Article 1 can compel either the UNSC to refer Syria’s case to the ICC or even goad states to action to action beyond dutifully co-operating with the UNSC. Thus one can state that under existing principles of International Law, there exists no obligation on non-state parties either under Treaty Law or under Customary law mandating compliance with the ICC.

To conclude it can be stated the problems for the ICC in Syria extent beyond the need for P5 unanimity for referral and requires a broader debate on UNSC- ICC coordination on the question of Sovereign immunity and obligations of non-state parties towards the ICC.

*Abraham Joseph is Ph.D. candidate in International Criminal Law from NLSIU, Bangalore and Assistant Professor in Ansal School of Law, Ansal University, Gurgaon. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

References

1. http://www.ejiltalk.org/who-is-obliged-to-arrest-bashir/

2. http://www.crimesofwar.org/commentary/the-icc-bashir-and-the-immunity-of-heads-of-state/

3. https://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/irrc_861_wenqi.pdf