TAPI – A Pipeline Of Peace In South Asia? – Analysis

By Dr. Shanthie Mariet D Souza

Even while consensus eludes the end-game in Afghanistan, and regional rivalry continues to complicate even a remote possibility of establishing peace in this conflict-ridden country, the economic windfall from an oil pipeline may yet help stabilise Afghanistan. The projected gains from the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline still retain the potential to create a win-win deal among regional stakeholders in Afghanistan.

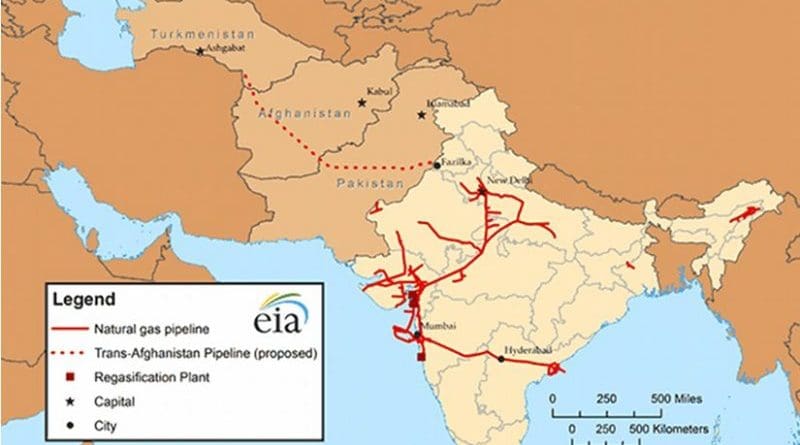

The TAPI project, expected to start in 2012 and be commissioned by 2016, envisages constructing 1,680 km of pipeline with a total gas capacity of 90 million standard cubic meters per day (mscmd). The proposed pipeline would stretch from Turkmenistan’s Dauletabad gas field and travel 1650 km through Turkmenistan (145 km), Afghanistan (735 km) and Pakistan (800 km), before culminating at the Indian border town of Fazilka in Punjab. It would carry 33 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually to consumers. As per the plan, 38 mscmd of gas would go to India and Pakistan each, while 14 mscmd would be bought by Afghanistan.

It is thus not altogether surprising that the US is propounding the project as ‘magic glue’ that will bind the warring factions and their regional proxies into an inter-dependent cooperative framework. The US also hopes that the TAPI pipeline will usher in economic interdependence among competing regional powers, thus making the costs of conflict too high and benefits of cooperation lucrative. TAPI will in all likelihood wean India away from the Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) gas pipeline from Iran’s South Pars gas complex in the Persian Gulf, one of the largest gas fields in the world. This would not only further isolate Iran, but the resultant interdependence and benefits of cooperation would possibly act as a catalyst for peace between India and Pakistan, narrowing differences between the two nuclear armed rivals in South Asia.

Afghanistan has much to gain. For an external aid-dependent ‘rentier state’ like Afghanistan, the pipeline would provide opportunities for sparking economic growth, and generating revenue and employment — a recipe for long-term stability. The government in Kabul could earn upwards of $1.4 billion in transit fees annually. Moreover, this project allows Afghanistan to reduce its dependence on Iran, from where it sources almost 2,400 tons of gasoline per day using the land route. In early December 2010, Iran had imposed a fuel blockade on Afghanistan on the grounds that the oil it supplies is used by US and Nato forces operating in Afghanistan, although the Karzai government insists that the fuel has only been used for civilian purposes.

Iran, thus, fears being left out in the new energy export economy and the region’s rapidly developing web of natural gas and oil pipelines. Iran does share good relations with Turkmenistan, but it needs ever-growing supplies of Turkmen natural gas for its winter heating and fuel requirements and to pump gas to pressurise its aging oil fields to keep them productive. If TAPI is built, Turkmenistan’s dependence on Iranian export routes would be considerably reduced. Iran, therefore, would be unable to pressure Turkmenistan to accept energy deals on Tehran’s terms and Iran might be unable to afford market prices for Turkmen natural gas.

Notwithstanding security concerns and the limited writ over much of the territory through which the pipelines pass, President Hamid Karzai has promised to ‘expedite’ the project’s completion. Afghan Minister of Commerce & Industry Wahidullah Shahrani has said that the government would deploy 500-7,000 security forces to safeguard the pipeline route.

Russia, which thus far had kept itself out of post-9/11 Afghan issues, entered into an understanding with the Afghan government during President Karzai’s visit last month, despite Turkmenistan’s public opposition to Russian involvement. As Russia tries to wrest control of the energy-surplus former states, the new states are assertive in trying to break free from such control. Russian-Turkmen relations turned sour in October 2010 after Russian envoy Igor Sechin claimed that Turkmenistan had agreed to allow Russian gas giant Gazprom to participate in the TAPI pipeline.

Turkmenistan immediately rebuffed the comments and denied that any such agreement had been brokered. Turkmenistan has been working to create an alternate pipeline network and to lower its dependence on Russia for certain gas exports. However, given Russia’s ability to delay or derail the TAPI project, it would be foolhardy to make any concerted attempt to keep the Russians away. India favours Gazprom’s participation as a supplier for the pipeline along with Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB), the lead partner in the project — expected to involve an investment of $6-7 billion — favours Chinese participation, taking into account the experience of Chinese firms in building long pipelines in a short time. India, however, remains wary of Chinese participation, which it apprehends would gradually amount to not only managing security issues in Afghanistan but also a larger regional role within Saarc, where Afghanistan is a full member.

A major factor, which will impinge directly on the fate of the project, would be political instability, issues of pricing and security considerations in the region. Since the birth of independent Central Asian states, the region has been plagued by political instability as witnessed by various ‘colour revolutions’. Similarly, in Afghanistan, the near absence of an effective police force, providing security for the pipeline, could turn this project into a lucrative protection-racket or cash cow for insurgents, local warlords or simply more dependence on private security armies and contractors, with little being done to build on Afghanistan national security institutions. Much will depend on the ability and commitment of the Afghan government and the international community to transform this economic opportunity into tangible benefits for the people of the region. Else, it would only lead to further entrenchment of vested interests and an unending cycle of conflict.

This article first appeeard at Business Standard and is reprinted with the author’s permission.