Emergence Of Jinnah As The Hero Of National Movement – Analysis

The formation of Muslim League in 1906 was a turning point in India’s history because its advent as an influential organisation transformed the Congress-British contest into a three-cornered fight that had multiple ramifications. Right from the beginning repeated efforts were made by the Congress as well as other organisations to settle the communal problem with the consent of the various groups concerned. Though the formation of the League was for the avowed purpose of promoting ‘among the Musalmans of India a feeling of loyalty to the British Government, a new leadership emerged in the League which reacted to such an attitude of servility and demanded that the League should take a full part in the struggle for national freedom.

It was piloted by the intellectuals like Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Ali brothers, under whose influence League, in 1913, adopted a resolution calling its objectives the attainment of self-government under the British, the promotion of national unity, and cooperation with other communities. To this the Congress responded warmly and the growing understanding between the two led to the famous “Lucknow Pact” of 1916.

Phase of leadership dilemma

Gandhi on account of an act of violence during the non-cooperation movement when public feelings ran high, called off the movement. It resulted in the arrest of Gandhi that followed a widespread frustration in Hindus and Muslims alike. The period of joint Hindu-Muslim militancy came to an end. Politically, Muslims were heterogeneous in character, had different interests and aspirations, and most of them were not interested in presenting a unified front at the all-India level.

Meanwhile, after the end of the movement a contrary process set in. The reactionaries within both communities exploited the situation and began to create feelings of animosity between them. Both the Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha took to belligerent communal propaganda. There were a series of communal outbreaks during the period following the Non-Co-operation Movement. But behind these communal forces of the time social disparities were the main cause as remarked Jawaharlal Nehru, ‘Hindu and Muslim communalism is, in neither case, even bona fide communalism, but political and social reaction hiding behind the communal mask. In fact, communalism was mainly the result of the peculiar development of the Indian social economy under the British rule, of the uneven economic and cultural development of different communities, and of the action of the strategy both of the British government and the vested interests within those communities.

As the political awakening of the Muslim masses increased, its professional classes and the bourgeoisie began to compare themselves with their counterparts in Hindu community who had established earlier in government services and had taken a key position in trade, industry and finance. This newly developed upper-middle class of the Muslim community needed the support of the masses among whom the national consciousness had arose due to the nationalist movement of the country.

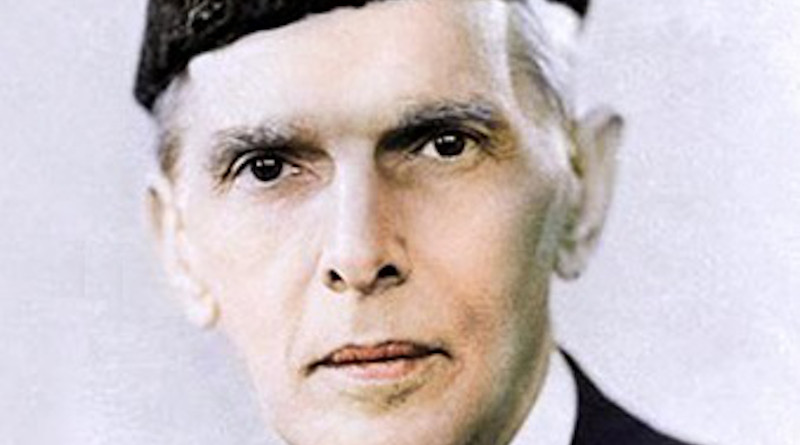

Role of Jinnah in Muslim League

Mohammad Ali Jinnah, when came back from England as a changed man, represented this deformed form of communalism which barred nothing to achieve the destination. Hence he adopted a multi-pronged policy to establish himself firmly not only in Muslim League, but in the politics of the sub-continent as a whole. His first step in this direction started with presentation of a fourteen-point programme before the League which apart from communal representation and schemes of weightage and Muslim veto on certain kinds of legislation, asked for a declaration of certain provinces as “Muslim-majority areas” for all time to come. It became the basis of Muslim demands at the first and second Round Table Conferences, after which the British Prime Minister declared a “Communal Award” which conceded almost all they had asked.

The All-India Muslim Conference, which represents at the conference was entrusted the task of extending the advantaged gained by the Muslim-majority provinces. However, its composition was an uneasy amalgam of conflicting interests. The conservative nationalists, represented by the rump of the Central Khilafat Committee and the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind, had to join hands with the arch loyalists—the princes and landlord parties—as well as various other organisations.

At organisational level, Jinnah removed the differences within the Muslim League and gave it an all-India stature, to which his own stature too, was attached. For him the problem at this stage was clear : how could a party geared to the objective of Muslim unity under a central leadership meet the expectations of the Muslim political groups whose orientation was basically local ? So his two-pronged tactic was to use sectarian propaganda to heighten communal tensions and, on the other hand to come to some agreement with the provincial groups. He co-opted the community based parties and their leaders, who had previously resisted being associated with the League. All who had fought elections on non-League tickets, now joined hands with Jinnah. But in the Muslim-majority provinces it was done as a reaction to the electoral success of the Congress that allowed the Muslim League to have a toe-hold, by exploiting their fear of a Congress-dominated centre wherever they would be a loser.

Jinnah undisputed leader of the League

These pacts and growth of understanding with the provincial leaders made Muslim League an spokesman of Muslim voice in India and Jinnah, an undisputed leader of the Party. He, in a determined effort to consolidate the League’s position and pull the remaining urban Muslim organisation into the ambit used his concept of Muslim nationalism. League under his leadership activated the Muslim-urban elites which made difficult for pro-Congress Muslim groups to operate smoothly. They were cornered in their community, no option left for many, but to join League or League-based alignments.

With this mentality, stature and influence Jinnah began to pressure for his share of power and position in the subcontinent. His bargain with the Congress and the British government was not for a separate state for the Muslims but a state within the State. In course of his efforts to gain maximum benefit and privileges for the community, his differences, particularly with the Congress leaders intensified, resulting in the solidification of attitudes on both sides.

The tussle between the British and the Congress created an opportunity for the Muslim League to grow into an all-India Party. In reality Jinnah had made major concessions to the Muslim-majority provinces to gain their support and in the process, was reduced to becoming their vakil at the centre. Jinnah’s political survival depended on the success of this gambit of turning the Muslim League into a credible all-India force. Again it got an opportunity to enhance its image when the World War II, started and the Muslim League supported, although conditional as it was, to win the government’s favour. It impressed the Raj and it saw Jinnah as a useful ally and began to stress the importance of the League’s viewpoint, strengthening it as a counterbalance to the Congress, implicitly accepting its claim that it spoke for all Muslims.