‘Godless Saracens Threatening Destruction’: Modern Christian Responses To Islam And Muslims – Analysis

By Daniel Pipes*

Following a millennium of almost uninterrupted hostility toward Islam and Muslims,[1] Christian hostility toward both declined. In a series of major shifts, European imperialism and secularism overcame the age-old fears of conquest and of false doctrine. In the process, Christians also noticed that Islam was not the horrible trick that it once seemed. To a considerable extent, admiration, sympathy, and even feelings of guilt vis-à-vis Muslims developed, something nearly unimaginable before 1700. Still, the old legacy remains extant and notably revived with the surge of Islamism and immigration to the West during the past half-century.

The following account looks first at several kinds of changes and then at several kinds of continuities. The main changes are three-fold: European strength of arms, lessened religious sentiments, and a Left seeking allies.

Changes: European Imperialism

On two occasions, premodern Europeans responded with counterattacks to Muslim campaigns of conquest against Christendom. The Arab empire sparked Byzantine, Spanish, and Crusader assaults. The Ottoman expansion into Europe met with modern European imperialism. That said, an essential difference distinguished the first round from the second. In 1248, French and Egyptian troops met as rough equals. But, centuries of stasis and decline among Muslims and development among Christians meant that, after 1700, European armies clearly and consistently took the offense. In 1798, when French and Egyptian troops met again, the balance had shifted overwhelmingly in the Christians’ favor.[2]

The year 1699, when the Ottoman Empire signed the highly disadvantageous Treaty of Carlowitz with the Holy League, marks the commonly accepted date for this shift. After that, Europeans had the power to confront Muslims directly; the latter, after more than a millennium of threatening Europe, now had to defend themselves from an unequivocal military superiority, which Europeans eagerly exploited.

This disparity led to Europe’s conquest of nearly all Muslim-majority territories during one and a half centuries, subduing about 95 percent of Muslim peoples.[3] The conquests took off in 1764 when the East India Company occupied Bengal and continued until 1919, when Christians ruled all Muslim-majority territories except Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Arabia, and Yemen (other Muslim-majority areas fell under Thai and Chinese control). A European balance of power permitted the first three states to stay independent while the latter two offered too little benefit to inspire European imperial ambitions.

In total, twelve modern European and four other majority-Christian states conquered overseas territories containing Muslim communities: the United Kingdom, Portugal, Spain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Italy, Greece, Russia, Ethiopia, the Philippines, and the United States. They competed avidly with each other, often going to war among themselves, implying that this assault took place without plan or conspiracy.

Reversing the premodern order, Europeans now encircled Muslims, dissipating traditional Christian anxieties about Islam while imbuing a spirit of supremacy, which they often connected to the Christian faith. Europeans exalted in their new-found power. In the words of historian Henry Dodwell, the “growing sense of military inferiority was carrying with it a multitude of moral consequences.”[4] Muslims no longer represented a force poised to destroy Christendom but now appeared to most Christians as poor, blighted, and backward peoples in need of European rule and tutelage.

Note the rapid change: In 1686, the British diplomat Paul Rycaut called Muslims the “scourge of Christianity.”[5] By 1807, William Jones, the founder of modern linguistics and professor of Arabic at Cambridge University, called the Arabs “a nation, who have ever been my favourite.”[6]

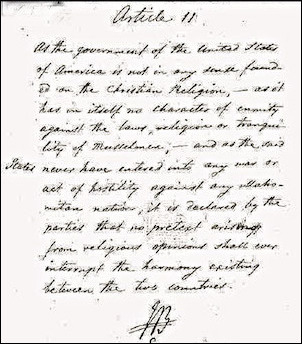

This relaxation in attitude had foreign policy consequences, too; thus, the nascent United States of America declared in a 1796 treaty with Barbary States that it “has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen” and called for “harmony” between the two sides.[7] Dissidents like Wilfrid Scawen Blunt in Egypt and Sudan or Edward Granville Browne in Iran sympathized with colonized Muslims fighting European governments.

Changes: Religious Relaxation

The change in the balance of power occurred simultaneously with a reduction in Christian religiosity, permitting more varied and nuanced views of Muhammad, Islam, and Muslims. Anger at the supposed deceit of Islam and outrage at Muslim sexual practices subsided. The traditional form of Christian hostility lost its hold on Enlightenment intellectuals who saw Islam as no worse than Christianity. Indeed, Enlightenment antagonism toward organized Christianity even led to praise of this hereditary enemy.

Ironically, the historically low regard for Islam now turned its prophet into a vehicle to express anti-Church sentiments. The historian Thomas Carlyle called Muhammad a “hero”[8] while the playwright George Bernard Shaw dubbed him “the wonderful man … the Saviour of Humanity.”[9] Some freethinkers, including Voltaire and Napoleon Bonaparte, favored Islam over Christianity. This new openness led to other reassessments: Orientalists like Edward Lane studied Islam and Muslims in a self-consciously detached and objective spirit. Mystics like Louis Massignon became deeply engaged in Islam the faith. Malcontents like St. John Philby converted to Islam as a vehicle of protest. Their collective spirit influenced popular attitudes toward Muslims, which became less antagonistic and excitable.

Imaginative works captured the new sense of strength and light-heartedness. A fictitious Turkish spy with an attractive personality and a lively sense of humor—not something Europeans hitherto expected of a Muslim—starred in the eight volumes of L’espion turc in the 1680s-90s, and Muslim countries won favorable treatment. Likewise, Montesquieu used the vehicle of letters home to Iran in Lettres persanes in 1721 to comment on French society, something previously outlandish.

Turquerie, the fashion to portray European subjects in Turkish costume or in a Turkish environment, also signaled a change in attitudes starting in the 1720s and lasting some decades. The historian Peter Hughes writes that while “Turkey on the whole aroused less philosophical admiration than China,” it had a special draw:

The appeal which Turkish subjects evidently exercised, with their allusions to seraglios, sultanas, oriental baths, and so on, was that of giving a very slightly lubricious character to the paintings in which they appeared. … At this date in European history, the Ottoman Empire was no longer felt to be alarming by sophisticated people, and there was clearly a certain piquancy in the relationship of a young woman of perfectly European appearance, like the mistress in [Charles André] Van Loo’s painting, with a Grand Turk.[10]

As whimsical attitudes replaced morbid concern, the Muslim Orient for the first time turned into an object of romance and playful intrigue. Beginning with Lord Byron, young aristocrats went East in search of a new, softer kind of adventure. Richard Burton, who clandestinely visited Mecca and Medina, epitomized the fashionable explorer.

The Orientalist school of painting, led by Eugène Delacroix, gained wide popularity by portraying the Middle East in an exotic light. The Polish nobility came up with glamorous notions of a supposed Iranian (“Sarmatian“) origin. By 1870, Muslims had become so tame that a group of Freemasons founded the playful Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, complete with fezzes and New York City’s Mecca Temple. The Shriners, as they were called, “invited their audiences to release their Westernized, workaday woes and enjoy a carefree, absurd, Orientalist spectacle,” in the description of historian Jacob S. Dorman.[11]

The Thousand and One Nights became a favorite source of fantasy, for example in Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s symphonic suite Scheherazade. German Romantics such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (West–östlicher Divan) introduced Middle East themes into their writings; one of them, Friedrich Rückert (Oestliche Rosen), was even a distinguished professor of Oriental languages. English authors such as Rider Haggard (She) and Rudyard Kipling (Kim) also reflected this change in attitude. The prolific French novelist Pierre Loti (Fantôme d’Orient) transformed Turkish and Arab life into romantic puffery.

The 1920s saw an especially intense Orientalism among both whites and blacks in the United States. The British novel and American movie The Sheik, starring Rudolph Valentino in the title role, recounts a North Africa Bedouin abducting an English girl who eventually falls for his charms and finds happiness in his harem. The movie then spawned its own genre of “desert romance” (sporting such titles as When the Desert Calls and The Son of the Sheik) as well as popular music tunes (The Sheik of Araby). As Princeton’s L. Carl Brown notes, the appeal of these stories lay in a “willful rejection of reality in favor of pure fantasy.”[12]

American blacks took this positive attitude in a more serious direction, seeing the Moor and the Muslim as positive avenues to escape racial discrimination. Beginning with Noble Drew Ali and then W.D. Fard, Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, and Louis Farrakhan, a series of charismatic figures developed folk versions of Islam that took various forms, including the Moorish Science Temple of America, the Nation of Islam, and the Five Percenters. While these new religions had little in common with the normative Islam of seventh-century Arabia, they served as a bridge between Christianity and normative Islam for hundreds of thousands of blacks.

Elements of this Thousand and One Nights-style attitude survived long after a new reversal of power had left it outdated. Thus, in a popular American book The Arab World, published in 1962, the British writer Desmond Stewart could still state that a Western visitor to the Arabic-speaking countries enters “the realm of Aladdin and Ali Baba.”[13] Thus did happy fantasies die only slowly.

Changes: The Left Discovers Islamism

These sympathetic views acquired enhanced political import in the 1970s and the rise of Islamism. At that time, the “certain piquancy” that Hughes had identified now applied to forming alliances with Islamists.

This phenomenon took form with the first major Islamist development to impinge on Westerners, the Iranian Revolution of 1978-79.[14] The key event appears to have been when the leftist French intellectual Michel Foucault delighted at what he witnessed first-hand in Iran and called Ayatollah Khomeini a “saint.” Ramsey Clark, a former U.S. attorney general, offered his support on a visit to Khomeini.[15] Prominent Latin America leftists such as Fidel Castro, Hugo Chávez, and Che Guevara’s son Camilo went on pilgrimages to Tehran. British politician Jeremy Corbyn took the mullahs’ money and turned up on Iranian television.[16]

The 9/11 attacks inspired similar praise. German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen termed them “the greatest work of art for the whole cosmos” and American novelist Norman Mailer deemed its perpetrators “brilliant.” In like spirit, Noam Chomsky, the MIT professor, visited the Hezbollah leader and endorsed its armed program. Ken Livingstone, a Trotskyite and mayor of London, physically embraced Islamist thinker Yusuf al-Qaradawi.[17] In his campaign for U.S. president in 2004, Dennis Kucinich quoted the Qur’an, urged a mosque audience to chant “Allahu Akbar” (“God is Great”), and proudly announced, “I keep a copy of the Koran in my office.”[18]

A number of important leftists—Lauren Booth, H. Rap Brown, Keith Ellison, George Galloway,[19] Roger Garaudy, Yvonne Ridley, Ilich Ramírez Sánchez (“Carlos the Jackal”), and Jacques Vergès—took the next step and converted to Islam.

The Left-Islamist (or Red-Green) alliance has several bases. First, the two sides share a common existential opponent. Galloway explains: “the progressive movement around the world and the Muslims have the same enemies,” by which he means Western civilization, and in particular his own Great Britain, the United States, and Israel, plus Jews, believing Christians, and capitalists.[20] Sánchez argued that “only a coalition of Marxists and Islamists can destroy the United States.”[21]

Second, the Left and Islamists share specific political goals: as anti-imperialism (but only in the case of the West), an Iraqi victory over coalition forces, the War on Terror to be terminated, anti-Americanism to spread, and the elimination of Israel. Conversely, they concur on the need for mass immigration and multiculturalism in the West. They effectively work together and jointly achieve more than they can separately. The first major example of this took place in Great Britain in 2001, when such organizations as the Communist party of Britain and the Muslim Association of Britain formed the Stop the War Coalition (a reference to Afghanistan and Iraq).

Third, the two sides mutually benefit from good relations. Islamists gain access to legitimacy, skills, and standing from the Left, while leftists gain cannon fodder. Douglas Davis of London’s Spectator calls the coalition

a godsend to both sides. The Left, a once-dwindling band of communists, Trotskyites, Maoists, and Castroists, had been clinging to the dregs of a clapped-out cause; the Islamists could deliver numbers and passion, but they needed a vehicle to give them purchase on the political terrain. A tactical alliance became an operational imperative.[22]

Davis quotes a British leftist who more simply explains: “The practical benefits of working together are enough to compensate for the differences.”

Fourth, Marxists see Muslims replacing the working class as the revolutionaries who will overthrow the existing bourgeois order. Marx predicted that the industrial proletariat would fulfill this role, but, instead, it became ever more affluent and failed to achieve its revolutionary potential, so the anticipated crisis in capitalism never came. Islamists replaced them, thereby fulfilling Marxist predictions, although working toward entirely different ends. The French radical Jean Baudrillard portrayed Islamists as the oppressed rebelling against their oppressors.[23] Olivier Besancenot, a French trade unionist, considers Islamists to be “the new slaves” of capitalism and finds it natural that “they should unite with the working class to destroy the capitalist system.”[24]

Continuities: Colonization

Favorable views dominated only if Muslims appeared unthreatening. Old views returned as Christian confidence dimmed due to four changes: the hard work of ruling subject peoples, the breakup of empires, Muslim reassertion of independence, and large-scale emigration to the West.

European imperialism and secularism did not eradicate all vestiges of medieval hostility toward Muslims, especially in the face of continued reciprocal Muslim enmity. Modern imperialism brought out latent Crusader and Reconquista impulses. Memories of the Crusades remained potent. Long-ago losses rankled and helped inspire the West European reconquest of many of those once-Christian lands; “Saladin, nous voilà” was how a conquering French general announced his arrival in Damascus in 1920.[25] In 1972, a diplomat referred to Muslim-Christian rivalry in the Sabah province of Malaysia: “What is happening in Sabah today is only a small reflection of what happened in the Crusades 1,000 years ago.”[26]

Imperialism brought Europeans into more contact, often hostile, with Muslims, thereby offering new scope to age-old animosities and increasing Christian-Muslim tensions. Many anti-colonial movements, such as those in Algeria and the Caucasus, had a distinctly Islamic quality. European subjugation of Muslims reduced historic fears of Islam but did not extinguish them, for Muslims generally resisted Christian rule with a special ferocity, as the French found in West Africa, the Germans in East Africa, the Russians in the Caucasus, the British in Afghanistan, and the Dutch in the East Indies. The Spanish, Americans, and Filipinos all learned this lesson in the Philippines.

When conquered, Muslims stood out in their reluctance to adopt European languages, culture, or religion, creating resentment among adminstrators and missionaries. Colonial rulers had to devise novel methods to rule their Muslim populations, such as le système Lyautey in Morocco or the Trucial States in the Persian Gulf. Worse, Muslims most often counterattacked, and the names of these incidents recall medieval confrontations: the Black Hole of Calcutta, the Indian Mutiny, the Bulgarian Horrors, the Alexandria Massacre, Gordon’s Last Stand, the Mad Mullah of Somalia, and the Great Fire of Smyrna. As historian Norman Daniel perceptively notes, “empire increased the inherited suspicion of Islam.”[27]

Continuities: Decolonization and Its Aftermath

The rapid decline of European power in the course of its extended civil war, 1914-45, revealed the limit of changes in Christian attitudes. If nearly the whole Muslim world fell to Europeans in a century and a half, independence from Europe came even more quickly, mostly in the twenty-year period 1945-65. The resumption of Muslim independence followed by the florescence of Islamism revealed that the age-old fear of Muslims had indeed remained in the shadows. Already in 1921, the notorious but learned racist Lothrop Stoddard noted: “The world of Islam, mentally and spiritually quiescent for almost a thousand years, is once more astir, once more on the march.”[28] A few years later, the American geographer Isaiah Bowman predicted that, of the problems facing the British and French empires, “none is so wide-ranging, none so fateful, as the question of control over large and bigoted if not fanatical Mohammedan populations.”[29] In 1946, a U.S. intelligence report found that “the Moslem states represent a potential threat to world peace.”[30]

After independence, renewed tensions further reawakened antique Christian anxieties. Muslims and Christians carried on their long tradition of conflict in such disparate places as Bosnia-Herzegovina, Cyprus, Lebanon, Chad, Sudan, Uganda, Eritrea, Mozambique, and the Philippines. Important milestones included Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal, the Algerian war of independence, the Arab oil embargo of 1973, the Iranian revolution, and wars in former Yugoslavia, Kuwait, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

The Iranian occupation of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in November 1979 lasted 444 days and offers a case study of revived passions: Beyond prompting a diplomatic crisis between two governments, this episode unleashed a mutual torrent of passions worth noting.

The hostage crisis inspired many thousands of Iranians to march on the streets and blame America for every conceivable ill in Iranian life “from assassinations and ethnic unrest to traffic jams [and] drug addiction.”[31] Iran’s leader, Ruhollah Khomeini, called America the “great Satan,” maligned its culture, and insulted its president. Americans responded in kind, excluding Iranian emigrants and painting Khomeini’s face on dartboards. Iranians provoked far more venom than any other nationality after World War II; in contrast, Koreans and Vietnamese, inspired only a fraction of this rage.

Prior U.S.-Iran relations could hardly account for this mutual hostility, the two states having benefited from consistently good relations from the time of W. Morgan Shuster’s trusty financial services in 1911 to Jimmy Carter’s exuberant New Year’s Eve toast to Iran in 1977 (“an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world).”[32] The two governments cooperated on many vital projects, especially in oil production and staving off Soviet aggression. Great numbers of Iranians had successfully studied in the United States as had American technicians worked in Iran. The passions on both sides pointed to something more than routine political tensions. If the history of U.S.-Iran contacts cannot account for the furies aroused in 1979-81, the explanation lies in the millennium-long history of Muslim-Christian hostility.

Continuities: A Negative Legacy

Indeed, Norman Daniel notes how “the medieval concept [of Islam] remained enormously durable [and] is still part of the cultural inheritance of the West today.”[33] Yes, the religious element declined in importance, but the old themes remained potent: For many Westerners, false belief, violence, deception, and fanaticism still characterize Muslims. In some cases, old tropes resurface unchanged, such as the argument that medieval Muslims were cultural parasites who created nothing but only stole from the peoples they conquered; or that taqiya (dissimulation) permits Muslims to lie at will.

Thus, old prejudices remained intact. William Gladstone, a British prime minister, described Turks in his sensational 1876 tract, Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East, as “the one great anti-human specimen of humanity. Wherever they went, a broad line of blood marked the track behind them; and as far as their dominion reached, civilization disappeared from view.”[34] A future prime minister, Winston Churchill expressed what many Europeans thought of Islam in his Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898):

the Mahommedan religion increases, instead of lessening, the fury of intolerance. It was originally propagated by the sword, and ever since its votaries have been subject, above the people of all other creeds, to this form of madness.[35]

In other cases, premodern attitudes toward Islam have been adjusted to fit the modern context. No one still claims Islam to be a Christian heresy; rather, the new accusation holds that Allah is actually the pagan moon-god Hubal.[36] Medieval claims that Islam is not a legitimate faith live on, but now with a political twist; Geert Wilders, the Dutch politician, argues that “Islam is not a religion. It is a totalitarian, dangerous and violent ideology, dressed up as a religion.”[37]

Sex remains a prominent, if shifting, focus of criticism. Muhammad was once reviled for his many wives; in keeping with the times, he is now excoriated as a pedophile. The medieval European notion of the Muslim woman as termagant (a “quarrelsome, overbearing woman; a virago, vixen, or shrew”) evolved into the early modern odalisque (“an abject harem slave”) and more recently into the victim of female genital mutilation, child marriage, polyandry, and honor killing. Fantasies of veiled women with lasciviously beckoning eyes gave way to female figures completely covered in their burqas; yet another British prime minister, Boris Johnson, compared them to letterboxes and bank robbers.[38] The once-glamorous “secret lives of the oil sheikhs”[39] transmuted into horror stories about female house slaves and abducted daughters.[40]

Traditional religious hostility toward Muslims diminished in the eighteenth century, replaced by a cultural antagonism. Muslims became less frightening, historian Bernard Lewis notes, but remained unpleasant to Christians: “a doctrinal hostility was superseded by a vaguer disapproval that arose in the course of actual contact.”[41] If Europeans no longer feared Muslims, the old distaste remained. As the U.S.-led war with Iraq began in 1991, Raymond Sokolov, a Wall Street Journal writer, attended a performance of Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio. He responded to the characters dressed as Turks and speaking pseudo-Turkish:

Neither Mozart’s joke nor Mozart’s basic situations make sense unless we agree, at least while we’re in the theater, that Muslims are absurd and malevolent. Last Thursday, it was not at all difficult to see things Mozart’s way.[42]

Wilfred Cantwell Smith finds it doubtful “whether Westerners, even those quite unaware that they are involved in such things, have ever quite got over the effects of this prolonged fundamental strife.”[43] Gai Eaton, a convert to Islam, pointed out in 1985 that

Less than three hundred years separate us from [the Treaty of ] Carlowitz, three hundred years in which Europeans could, at least until very recently, try to forget their long obsession with Islam. It was not easily forgotten.[44]

Hichem Djaīt stresses the longevity of medieval prejudices against Islam that “insinuated themselves into the collective unconscious of the West at a level so profound that one must ask oneself, with fear, whether they can ever be extirpated.”[45]

Continuities: Immigration

The substantial immigration of Muslims to Europe that started in the 1960s boosted its immigrant and convert population (ignoring Russia) from negligible to close to thirty million. The largest numbers came from North Africa, Turkey, and South Asia, but virtually all Muslim populations are now represented.

If immigration from outside the West generally involves many practical problems—unfamiliar diseases, linguistic difficulties, insufficient work skills, and high unemployment—Muslim newcomers often bring further complications that follow from their Islamic attitudes. Many concern women: niqabs and burqas, sexual predation, grooming and rape gangs, taharrush (gang sexual assault), marriages between first cousins, polygynous marriages, female genital mutilation, and honor killings. Other issues show hostile intent: partial no‑go zones, förnedringsrån (robberies intended to humiliate), slave-holding, violent responses to criticism of Muslims or Islam, violence to forward Islamic rule, and efforts to apply Islamic law to everyone.

In particular, intra-Muslim violence spilled into the West, leading to such murders as Palestine Liberation Organization leader Issam Sartawi in Portugal in 1983, former Iranian prime minister Shapour Bakhtiar in 1991, and Turkish dissidents in Paris in 2013. Jihad became especially important and included the murder of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972, the attempted assassination of Pope John Paul II in 1981, the 1989 Salman Rushdie edict, the 9/11 attacks, the 2004 Madrid bombing, the assassination of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh in 2004, the 2007 London bombing, and the 2015 Charlie Hebdo massacre. Unsurprisingly, these and other incidents further heightened Christian apprehensions.

Illegal immigration of Muslims prompted many political battles in Europe, especially in the geographically most exposed countries of Spain, Malta, Italy, and Greece. The greatest fights followed the surprise invitation by Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel to one and all to come to Germany, leading to about 1.5 million unvetted Muslims arriving in Europe and reverberating for years afterwards.

As Muslim immigration increases, poll after poll reveals emotions toward them and Islam become more negative. For example, already in 1986 and 1988, surveys of French attitudes consistently showed men and women both less likely to engage in sex with an Arab than with any of the other categories named (Africans, Asians, West Indians).[46] In 2013, 73 percent in a French sample viewed Islam negatively while 77 percent in a Dutch sample opined that Islam does not enrich the country.[47]

Today, some analysts see the West’s low birth rates, the large-scale immigration of Muslims to the West, the spread of multiculturalism, and creeping Islamization as a civilizational threat. Alan Jamieson closes his survey of Christian-Muslim conflict by noting, “In all the long centuries of Christian-Muslim conflict, never has the military imbalance between the two sides been greater, yet the dominant West can apparently derive no comfort from that fact” because the battlefield is not military.[48] Or, as Italian journalist Giulio Meotti puts it more starkly, “If Eastern Christianity can be extinguished so easily, Western Europe will be next.”[49]

Conclusion

Westerners tend to recall the Muslim threat more vividly than the positive interactions. Memories of conflict endure more powerfully than do those of trade, cultural exchange, and acts of tolerance. All but Sicilians, scholars, and tourists have forgotten Roger II, the Norman king of Sicily in whose court Muslim scholarship flourished during the Crusader era. The Andalusian heritage of convivencia (coexistence) has been depicted as an exaggeration, if not a fraud.[50] Nonetheless, Susana Martínez of the University of Evora in Portugal hopes this heritage can provide a solution:

We need to continue telling … the stories of common people and the way they interacted, the way they shared similar ways of living. These stories are a powerful way to deconstruct stereotypes and prejudice we might have about the other.[51]

I endorse this effort, but focusing on shared ways of life has less emotional impact than recalling tragic defeats and heroic victories. Indeed, the hostile confrontation along “the oldest frontier in the world” remains vivid. Historian Raymond Ibrahim starkly sums up this mentality: the “West and Islam have been mortal enemies since the latter’s birth some fourteen centuries ago.”[52]

This raises the question of culpability: who was the main aggressor? Norman Itzkowitz of Princeton University holds the West mainly responsible: “Christian Europe’s unending pursuit of victory over Islam in any age has poisoned the atmosphere and continues to do so today.”[53] More convincingly, Bernard Lewis, also of Princeton, finds that Muslims primarily drove the conflict:

for approximately a thousand years, from the advent of Islam in the seventh century until the second siege of Vienna in 1683, Christian Europe was under constant threat from Islam, the double threat of conquest and conversion.[54]

A glance at the dispersion of Christians and Muslims in 600 and in 1600 makes that conclusion indisputable.

The longevity and constancy of attitudes is remarkable. As Lewis establishes, Muslims developed an attitude of disdain toward Europe that lasted a millennium and persisted even into the era of European imperialism.[55] Christian feelings about Muslims were nearly the exact reverse: they feared and hated the Muslims with a constancy that lasted to about 1700, then abated over the next three centuries. Some Europeans left the old attitudes entirely behind, but hostility to Islam retains its historic hold among many others. In the words of yet another Princeton scholar, Charles Issawi, “The legacy of the long, sad past is still very much with us, and will continue to color images and bedevil relations between the West and the Islamic World for a long time to come.”[56]

*About the author: Daniel Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is president of the Middle East Forum.

Source: This article was published by the Middle East Forum in its Middle East Quarterly Spring 2021 Volume 27, Number 2

Appendix: Western Conquests of Muslim-majority Territories, 1764-1919

| 1764 Bengal (Britain’s East India Company) 1777 Balam-Bangan, Indonesia (Netherlands) 1783 Crimea (Russia)1786 Penang. Malaysia (Britain)1798 Egypt (France) 1799 Syria (France) 1800 Parts of Malaysia (Britain) 1801 Georgia (Russia)1803–28 Azerbaijan (Russia) 1804 Armenia (Russia) 1808 Western Java (Netherlands) 1820 Bahrain; Qatar; United Arab Emirates (Britain) 1830 Manchanagara, Indonesia (Netherlands) 1830–46 Algerian coast (France) 1834–59 Caucasus (Russia) 1839 Central Sumatra, Indonesia (Netherlands), Aden, South Yemen (Britain) 1841 Sarawak (Sir James Brooke, a Briton) 1843 Sind, India (Britain) 1849 Kashmir and Punjab, India (Britain), Parts of Guinea (France) 1849–54 Syr Darya Valley, Kazakhstan (Russia) 1856 Oudh, India (Britain) 1858 All India under British crown 1859 Daghestan (Russia) 1859–60 Tetuan, Morocco (Spain) 1864 Cimkent, Kazakhstan (Russia) 1866 Tashkent, Uzbekistan (Russia) 1868 Bukhara, Uzbekistan (Russia) 1872–1908 Aceh, Indonesia (Netherlands) 1873 Khiva, Uzbekistan (Russia) 1876 Khokand, Uzbekistan (Russia), Socotra, South Yemen (Britain), Quetta, Pakistan (Britain) 1878 Kars and Ardahan, Turkey (Russia), Bulgaria (Russia), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, (Austria), Cyprus (Britain) | 1878–79 Khyber Pass, Pakistan (Britain) 1881 Ashkhabad, Turkmenistan (Russia) 1881-83 Tunisia (France) 1882 Egypt (Britain), Assab, Ethiopia (Italy) 1883-88 Upper Niger Basin (France) 1884 Northern Somalia (Britain, France), Merv, Turkmenistan (Russia) 1885 Eastern Rumelia (Bulgaria), Rio de Oro, Mauritania (Spain) 1885-89 Eritrea, Ethiopia (Italy) 1887 Harar (Ethiopia) 1887-96 Guinea (France) 1888 North Borneo, Malaysia (Britain) 1889-92 Southern Somalia (Italy) 1890 Zanzibar, Tanzania (Britain) 1891 Oman (Britain) 1892-93 Lower Niger Basin (France) 1893 Uganda (Britain) 1896–98 Northern Sudan (Britain) 1898–1903 Northern Nigeria (Britain) 1898–99 Southern Niger (France) 1899 Kuwait (Britain) 1900–14 Southern Algeria (France) 1903 Macedonia (Russia and Austria) 1906 Wadai, Chad (France) 1908 Crete (Greece) 1909 Northern Malay Peninsula (Britain) 1911–28 Libya (Italy) 1912 Dodecanese (Italy), Western Sahara (Spain) 1912-34 Morocco (France and Spain) 1913 Southern Philippines (United States), Central Thrace (Bulgaria) 1914 All Malaysia (Britain) 1917 Israel; Jordan (Britain), Lebanon; Syria (France) 1918 Parts of Turkey (Italy, Greece, France) 1919 Iraq (Britain) |

[1] Detailed in part one of this study, Daniel Pipes, “‘Godless Saracens Threatening Destruction’: Premodern Christian Responses to Islam and Muslims,” Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2021.

[2] For a comparison of these two encounters, plus a third in 1956, see “Three French Invasions of Egypt,” an excerpt from Daniel Pipes, In the Path of God: Islam and Political Power (New York: Basic Books, 1983), pp. 98-101.

[3] See the Appendix for year-by-year details, derived from ibid., pp. 102-03.

[4] Henry Dodwell, The Founder of Modern Egypt: A Study of Muhammad ‘Ali (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1931), p. 2.

[5] Sir Paul Rycaut, The History of the Present State of the Ottoman Empire (London: R. Clavell, J. Robinson and A. Churchill, 1686), p. 213.

[6] The Works of Sir William Jones, Lord Teignmouth, ed. (London: John Stockdale and John Walker, 1807), p. 69.

[7] “Treaty of Peace and Friendship, signed at Tripoli November 4, 1796 (3 Ramada I, A. H. 1211), and at Algiers January 3, 1797 (4 Rajab, A. H. 1211),” in Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America, vol. 2, Hunter Miller, ed. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1931), doc. 1-40: 1776-1818.

[8] Thomas Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (London: Chapman and Hall, 1840).

[9] The Light (Vicksburg, Miss.), Jan. 24, 1933.

[10] Peter Hughes, Eighteenth-century France and the East (London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 1981), pp. 13-14.

[11] Jacob S. Dorman, The Princess and the Prophet: The Secret History of Magic, Race, and Moorish Muslims in America (Boston: Beacon Press, 2020), p. 52.

[12] L. Carl Brown, “Movies and the Middle East,” Comparative Civilizations Review, vol. 13, no. 13, Jan. 1, 1985.

[13] Desmond Stewart, The Arab World (New York: Time-Life Books, 1962), p. 13.

[14] This section draws on Daniel Pipes, “[The Islamist-Leftist] Allied Menace,” National Review, July 14, 2008.

[15] The New York Times, Jan. 23, 1979.

[16] Business Insider (New York), July 2, 2016.

[17] BBC News, July 12, 2004.

[18] Hugo Kugiya, “Audiences Small but Adoring: Kucinich undeterred by long-shot status,” Newsday, Feb. 10, 2004.

[19] Jemima Khan, “One day, I’ll be a national treasure,” The New Statesman (London), Apr. 25, 2012.

[20] The Boston Globe, May 20, 2007.

[21] Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, L’islam révolutionnaire (Monaco: Éditions du Rocher, 2003).

[22] Douglas Davis, “United in hate,” The Spectator, Aug. 20, 2005.

[23] Jean Baudrillard, La Guerre du Golfe n’a pas eu lieu (Paris: Galilée, 1991).

[24] Davis, “United in Hate.”

[25] James Barr, “General Gouraud: ‘Saladin, We’re Back!’ Did He Really Say It?” Syria Comment, University of Oklahoma, May 27, 2016.

[26] Far Eastern Economic Review, Nov. 25, 1972.

[27] Norman Daniel, Islam, Europe and Empire (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1966), p. 482.

[28] Lothrop Stoddard, The New World of Islam (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921), p. 355.

[29] Isaiah Bowman, The New World: Problems in Political Geography, 4th ed. (Yonkers, N.Y.: World Book, 1928), p. 124.

[30] “Intelligence Review,” Military Intelligence Div., War Dept., Washington, D.C., Feb. 14, 1946, p. 34.

[31] The New York Times, Jan. 6, 1980.

[32] Ibid., Jan. 2, 1978.

[33] Norman Daniel, Islam and the West: The Making of an Image (Edinburgh: The University Press, 1958), p. 278.

[34] William Gladstone, Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East (New York and Montreal: Lovell, Adam, Wesson, and Co., 1876), p. 10.

[35] Winston Churchill, The Story of the Malakand Field Force (London: Longman, 1898), p. 40.

[36] Robert A. Morey, The Moon-god Allah in the Archeology of the Middle East (Las Vegas: Faith Defenders, 1994).

[37] “Geert Wilders: “In My Opinion, Islam Is Not a Religion,” Gatestone Institute, Sept. 16, 2017.

[38] The Telegraph (London), Aug. 5, 2018.

[39] Linda Blandford, Super-Wealth: The Secret Lives of the Oil Sheikhs (New York: William Morrow, 1977).

[40] USA Today, Nov. 21, 2001; The Guardian (London), Mar. 5, 2020.

[41] Bernard Lewis, The Muslim Discovery of Europe (New York: Norton, 1982), pp. 482-3.

[42] Raymond Sokolov, “Mozart and the Muslims,” The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 23, 1991.

[43] Wilfred Cantwell Smith, Islam in Modern History (Princeton, N.J., and London: Princeton University Press and Oxford University Press, 1957), p. 106.

[44] Charles Le Gai Eaton, Islam and the Destiny of Man, 1st ed. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985), p. 18.

[45] Hichem Djaīt, L’Europe et l’Islam (Paris: Seuil, 1978), p. 21.

[46] Le Nouvel Observateur, June 24, 1988.

[47] Daniel Pipes, “Anti-Islam & Anti-Islamism Trumps Islam in the West: Polls,” DanielPipes.org, Nov. 24, 2013.

[48] Alan Jamieson, Faith and Sword: A Short History of Christian-Muslim Conflict (London: Reaktion Books, 2006), p. 215.

[49] Giulio Meotti, “Europe: Destroyed by the West’s Indifference?” Gatestone Institute, Nov. 19, 2017.

[50] Darío Fernández-Morera, The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise (Wilmington, Del.: ICI Books, 2016).

[51] Marta Vidal, “Portuguese Rediscovering Their Country’s Muslim Past,” Al-Jazeera, June 10, 2020.

[52] Raymond Ibrahim, Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West (New York: Da Capo, 2018), p. xvii.

[53] Norman Itzkowitz, “The Problem of Perceptions,” in L. Carl Brown, ed., Imperial Legacy: The Ottoman Imprint on the Balkans and the Middle East (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), p. 34.

[54] Bernard Lewis, Islam and the West (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 127.

[55] In Lewis, The Muslim Discovery of Europe.

[56] Charles Issawi, “The Change in the Western Perception of the Orient,” in The Arab World’s Legacy: Essays (Princeton, N.J.: Darwin Press, 1981), p. 371.