India’s Ill-Conceived Gambit In J&K – Analysis

By SATP

By Ajai Sahni*

Even as New Delhi was mulling the possibilities of extending its ‘unilateral ceasefire’ [‘non-initiation of combat operations’ by the Security Forces (SFs) during Ramzan] beyond Eid, the murder of Shujaat Bukhari, editor of Rising Kashmir, with two security guards, as well as the abduction and murder of a soldier of the Rashtriya Rifles, Aurangzeb, underscore the inherent dangers of a blind political gambit, launched in the hope that ‘something positive’ could emerge. After decades of counter-insurgency experience, and the demonstrable failure of past ‘unilateral ceasefires’, policy planners continue to ignore the fundamental dynamics of violence in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), squandering the operational gains SFs obtain over months and years, at a time of their increasing dominance, in what amounts to nothing more than a gamble and a hope. Unsurprisingly, after the Bukhari and Aurangzeb killings, the Centre abandoned all idea of a ‘ceasefire’ extension.

Before the Bukhari and Aurangzeb killings, both the Centre and the State Government had begun to package the ceasefire as a success, principally on the specious grounds that ‘stone pelting’ incidents had declined dramatically in the Valley. Partial data compiled by the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) indicates that such incidents dropped from 19 between April 17 and May 16, resulting in 10 fatalities and 207 persons injured; to 14 incidents between May 17 (the date of the commencement of the ceasefire) to June 17 (the date on which the MHA announced the end of the ‘ceasefire’), resulting in three fatalities and 56 persons injured. Such incidents, in the preceding months, had essentially occurred in the wake of narrowly targeted intelligence based operations by SFs, against identified terrorists. The pelting was orchestrated to disrupt these operations and facilitate the escape of the cornered terrorists. The decline in pelting incidents was the natural and inevitable consequence of the moratorium against SF-initiated operations and was a manifestly false index of the ‘success’ of the ceasefire.

It is useful, in this context, to note that there was no decline in incidents of or fatalities due to terrorist violence in this phase, as compared to the month preceding. Thus, SATP data indicates, there were at least 24 terrorism-related incidents between April 17 and May 16, 2018, resulting in 36 fatalities. Between May 17 and June 17, there were 64 such incidents, with 36 fatalities. Both SF and terrorist fatalities rose, from five to nine in the first category, and from 14 to 23 in the latter. Further, the number of explosions over these periods rose from two (leaving five injured, no fatalities) to 20 (68 injured, no fatalities). However, fatalities in the civilian category declined significantly, from 17 in the April 17 – May 16 period, to four through May 17 – June 17. The Bukhari killing, however, demonstrates the transient and illusory nature of any sense of greater security in this category as well.

As the illusion of the ‘success’ of the ceasefire gained ground in J&K and in the echo chambers of Delhi’s media, however, the Centre sought aggressively to project this initiative as a planned strategic venture, something that had been set up over the preceding months through ‘back channels’, and based on a conscious calculus of success. Circumstances surrounding the declaration of the ceasefire, however, militate against such a narrative. First, and crucially, the ceasefire call came from Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti as an ‘appeal’ to the Centre, and left New Delhi dithering for nearly a week, before it was conceded – most likely because it had been cast into the form of a plea to ‘respect’ Muslim ‘sentiments’. Worse, not a single significant separatist formation, and certainly no terrorist faction, had been taken on board, and these were unanimous in their rejection of the initiative. Crucially, through the month of the Ramzan ceasefire, no worthwhile ‘political’ initiative crystallized to suggest that a broader scheme was in place. The ceasefire was an end in itself, based on nothing more than a wing and a prayer.

What is it that leads policy-makers into these traps again and again, despite the enormous and cumulative experience of history? In the present context, one of the most significant factors has been the continuous and hysterical evaluations of the ground situation in J&K, and particularly in the Valley, over the past nearly two years. Indeed, much commentary and policy has reflected the most alarmingly ignorant assessments since the escalation of street and terrorist violence in the wake of the killing of Hizb-ul-Mujahiddeen ‘commander’ Burhan Wani in July 2016. Authoritative commentators, at least occasionally buttressed by statements from the political and security establishment, have spoken of the situation having ‘returned to the 1990s’ – an assertion that goes well beyond the absurd, deserving to be dismissed with contempt had it not resulted in grave consequences.

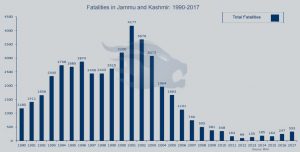

It is useful, consequently, to place current trajectories of violence in J&K within a rational context. First, it is necessary to dispel the ludicrous belief that we are in a situation that, in any manner, resembles the 1990s. From 1990 to 2006, J&K witnessed a ‘high intensity conflict’, with terrorism-linked fatalities exceeding a thousand in each year. In 11 of these years, from 1993 to 2004 (inclusive), fatalities exceeded two thousand per annum; for four years (2000 to 2003, inclusive), more than three thousand persons lost their lives in terrorism related-incidents each year; and, at peak in 2001, fatalities stood at 4,177 [MHA data].

After 2001, there was a continuous and dramatic decline in fatalities, bottoming out at 99 in 2012 [MHA data]. Thereafter, an increasingly myopic and polarizing politics by establishment parties – predominantly Islamist in the Valley and Hindutva in the Jammu region – has expanded spaces for extremist mobilisation. The terrorists and their Pakistani state sponsors have not spurned the opportunities gifted to them by our own political folly. There has been a relative resurgence of terrorist activities, with fatalities rising to 135 in 2013; 185 in 2014; dipping slightly to 164 in 2015; rising again to 247 in 2016; and to 333 in 2017 (MHA data). SATP data puts fatalities in 2018 at 173 (till June 17).

After 2001, there was a continuous and dramatic decline in fatalities, bottoming out at 99 in 2012 [MHA data]. Thereafter, an increasingly myopic and polarizing politics by establishment parties – predominantly Islamist in the Valley and Hindutva in the Jammu region – has expanded spaces for extremist mobilisation. The terrorists and their Pakistani state sponsors have not spurned the opportunities gifted to them by our own political folly. There has been a relative resurgence of terrorist activities, with fatalities rising to 135 in 2013; 185 in 2014; dipping slightly to 164 in 2015; rising again to 247 in 2016; and to 333 in 2017 (MHA data). SATP data puts fatalities in 2018 at 173 (till June 17).

The fatalities in 2017, at well over three times the figure for 2012, are certainly a cause for grave concern. In comparison to the 1990s and early 2000s, however, they are a minuscule fraction, and are just 7.97 per cent of peak fatalities in 2001.

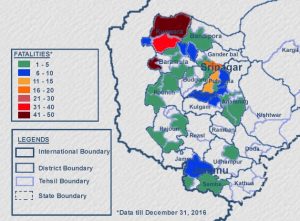

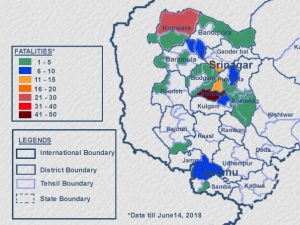

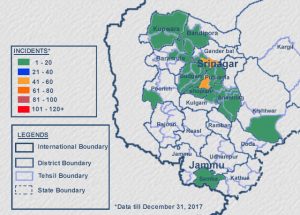

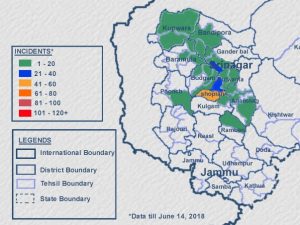

More significantly, where the entire J&K State, excluding the Ladakh region, was afflicted by terrorist violence and separatist disorders in the 1990s and early 2000s, current violence is sparse and localized, leaving wide areas, even of the Valley, unaffected or marginally affected. The idea even that the whole of the Kashmir Valley is aflame is the product of feverish imaginations and in no measure resembles reality. Maps plotting SATP fatalities data across the 82 tehsils (sub-districts) of J&K through 2016 and 2017 provide a clear visual index of both the localized nature of violence as well as the wide regions that are free of, or marginally affected by, terrorist activities across the State.

More significantly, where the entire J&K State, excluding the Ladakh region, was afflicted by terrorist violence and separatist disorders in the 1990s and early 2000s, current violence is sparse and localized, leaving wide areas, even of the Valley, unaffected or marginally affected. The idea even that the whole of the Kashmir Valley is aflame is the product of feverish imaginations and in no measure resembles reality. Maps plotting SATP fatalities data across the 82 tehsils (sub-districts) of J&K through 2016 and 2017 provide a clear visual index of both the localized nature of violence as well as the wide regions that are free of, or marginally affected by, terrorist activities across the State.

The data shows that, in 2016, just 29 of 82 tehsils recorded any fatalities. Crucially, the five worst affected tehsils accounted for at least 58.42 per cent of all killings. 2017 saw a greater dispersal of the violence, with 32 tehsils recording fatalities, of which just five accounted for 40.2 per cent.

In 2018, the spread of violence diminished again, with 29 tehsils recording terrorism-related fatalities, with just the worst five accounting for as much as 60.69 per cent of all killings (data till June 17). In the Valley, at least 17 tehsils of a total of 39 tehsils recorded no fatalities in 2016, 12 in 2017, and 14 in 2018. Just six of 39 tehsils in the Valley recorded 11 or more fatalities in 2016; 13 in 2017; and only four of 39 in the current year (till June 17).

In 2018, the spread of violence diminished again, with 29 tehsils recording terrorism-related fatalities, with just the worst five accounting for as much as 60.69 per cent of all killings (data till June 17). In the Valley, at least 17 tehsils of a total of 39 tehsils recorded no fatalities in 2016, 12 in 2017, and 14 in 2018. Just six of 39 tehsils in the Valley recorded 11 or more fatalities in 2016; 13 in 2017; and only four of 39 in the current year (till June 17).

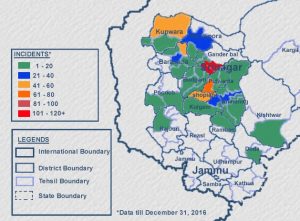

Crucially, the stone pelting campaigns tend to mirror these trends. Thus, official data plotted across the 206 Police Station jurisdictions in J&K (of which 103 are in the Valley), shows that the worst ten Police Station jurisdictions in the Valley accounted for 42.1 per cent of 2,647 incidents in 2016; the worst 20, for 65.16 per cent of all incidents; and the worst 30 for 77.82 per cent.

On the other hand, the ten least affected Police Stations saw just 20 incidents (0.75 per cent) through 2016; the 20 least affected, 67 incidents (2.53 per cent); and the 30 least affected in the Valley, 155 incidents (5.85 per cent) through 2016.

On the other hand, the ten least affected Police Stations saw just 20 incidents (0.75 per cent) through 2016; the 20 least affected, 67 incidents (2.53 per cent); and the 30 least affected in the Valley, 155 incidents (5.85 per cent) through 2016.

Similarly, in 2017, the worst 10 Police Stations accounted for 741 (52.47 per cent) of a total of 1,412 incidents; the worst 20, 1,028 incidents (72.8 per cent); and the worst 30, 1,186 incidents (83.99 per cent) of all incidents.

Conversely, the least affected 10 Police Stations saw just two incidents (0.14 per cent of the total); the least affected 20, 13 incidents (0.92 per cent); and the least affected 30, registered 35 incidents (2.47 per cent) in the Valley, through the year.

| PSs | 2016 | 2017 |

| Worst Five PSs | 685 (25.87%) | 484 (34.27%) |

| Worst 10 PSs | 1,116 (42.1%) | 741 (52.47%) |

| Worst 20 PSs | 1,725 (65.16 %) | 1,028 (72.8%) |

| Worst 30 PSs | 2,060 (77.82%) | 1,186 (83.99%) |

| Least affected 5 in Valley | 6 (0.22%) | 0 (0%) |

| Least affected 10 in Valley | 20 (0.75%) | 2 (0.14%) |

| Least affected 20 in Valley | 67 (2.53%) | 13 (0.92%) |

| Least affected 30 in Valley | 155 (5.85%) | 35 (2.47%) |

| Total PSs in J&K: 206

103 in Kashmir Valley 97 in Jammu 6 in Ladakh |

2,647 incidents | 1,412 incidents |

| Summary Data: Stone pelting 2016-17, official sources |

Detailed official data for 2018 is unavailable, as is a map of Police Station jurisdictions in J&K. However, SATP’s partial data for pelting incidents across tehsils in J&K illustrates comparable patterns. Of 214 incidents recorded in 26 of 82 tehsils in J&K in 2018, the worst five tehsils accounted for 66.82 per cent of all incidents. A visual representation of SATP data shows wide areas that remain unaffected or marginally affected by the orchestrated pelting campaigns.

The Ramzan ceasefire has, of course, had some incidental benefits. The sharp decline in civilian fatalities, the absence of proactive operations by SFs and of the attendant, often coercive mobilisation for stone pelting, and a general atmosphere of relative peace – albeit deceptive – has brought psychological relief to the Valley.

The Ramzan ceasefire has, of course, had some incidental benefits. The sharp decline in civilian fatalities, the absence of proactive operations by SFs and of the attendant, often coercive mobilisation for stone pelting, and a general atmosphere of relative peace – albeit deceptive – has brought psychological relief to the Valley.

Crucially, all terrorist operations in this period are squarely within the ambit of Pakistani mischief. Of the nine incidents of attributable terrorist violence during the ceasefire period, not even one has been credited to the Hizb-ul-Mujahiddeen (HM), the ‘local’ Kashmiri formation – headquartered, of course, at Muzzafarabad in Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK) – despite the fact that its ‘high command’ had immediately rejected the ceasefire at the time of its announcement. Four incidents have been attributed to the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), and another five to Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), both explicitly Pakistani formations.

An intensive effort to escalate the conflict during Ramzan was visible in the ceasefire violations by Pakistan along the Line of Control (LoC) and International Border (IB). While SATP recorded a total of 10 incidents of violations of the Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) during the April 17 – May 16 period, resulting in three fatalities (all SF), the number rose sharply to 67 such violations during the Ramzan ceasefire, between May 17 and June 17, resulting in 19 fatalities (eight SF and 11 civilian).

An intensive effort to escalate the conflict during Ramzan was visible in the ceasefire violations by Pakistan along the Line of Control (LoC) and International Border (IB). While SATP recorded a total of 10 incidents of violations of the Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) during the April 17 – May 16 period, resulting in three fatalities (all SF), the number rose sharply to 67 such violations during the Ramzan ceasefire, between May 17 and June 17, resulting in 19 fatalities (eight SF and 11 civilian).

Interestingly, on June 14, the day that Shujaat Bukhari was murdered, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) released a report on The Situation of Human Rights in Kashmir. It is not possible, or, indeed, relevant, to attempt any detailed assessment of this report here, but, since it has been injected into situation undergoing rapid transformation and an uneven progression towards stabilization, it is useful to point out that the report is riddled with contradictions and infirmities of approach that would make a cub reporter cringe.

The report begins with a confession that, “Without access to Kashmir on either side of the Line of Control, OHCHR has undertaken remote monitoring of the human rights situation.” As it relies on a handful of one-sided sources, and studiously ignores complexities that go beyond grievance harvesting, the report has rightly been rejected by the Government of India as a “selective compilation of largely unverified information.” Crucially, the report was noticeably welcomed by Pakistan and, perhaps more significantly, applauded by Hafiz Mohammad Saeed, the head of the LeT–Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD) terrorist complex, giving a fair indication of the constituencies expecting to benefit the most from this exercise.

The report begins with a confession that, “Without access to Kashmir on either side of the Line of Control, OHCHR has undertaken remote monitoring of the human rights situation.” As it relies on a handful of one-sided sources, and studiously ignores complexities that go beyond grievance harvesting, the report has rightly been rejected by the Government of India as a “selective compilation of largely unverified information.” Crucially, the report was noticeably welcomed by Pakistan and, perhaps more significantly, applauded by Hafiz Mohammad Saeed, the head of the LeT–Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD) terrorist complex, giving a fair indication of the constituencies expecting to benefit the most from this exercise.

Nevertheless, widening areas free of terrorist and separatist violence in the Valley and the increasing role of Pakistani terrorist formations, to the exclusion of HM, are among the many markers of the growing chasm between the separatists and the average Kashmiri, and of a rising impulse against extremist violence (though this does not necessarily translate into a pro-India sentiment). This cannot be strengthened by initiatives that undermine the very basis of this impulse – the progressive erosion of the operational capacities of terrorist groups – and by the adventurism of ill-informed ‘peace processes’. The muddled and muddy rhetoric of a ‘political solution’, lacking any hint of detail, and of ‘dialogue’ without any possibility of drawing the parties in conflict to the table, deepen prevailing contradictions and encourage those whose principal negotiating tool is violence.

Mere political optics cannot be allowed to become the framework for strategic calculations and policy initiatives. The duty and objective of the state is not to create the illusion of security, but to harden its reality. The search for a magical ‘solution’ to the enduring conflict in Kashmir and the seduction of impulsive ‘peacemaking’, have long proven dangerous and counter-productive.

It is folly to believe, as the terrorists, the separatists and their handlers would like us to, that there is no politics in J&K as long as SF operations are ongoing; or that there is no conversation occurring in the State if the SFs are not ordered to stand down. SF successes have already created the environment, both for increasingly effective politics and for a vigorous – often noisy and disordered – dialogue with and among the people. Directionless and desperate gambits such as the Ramzan ceasefire not only undermine the pace of SF operations, they provide relief to separatist and terrorist elements at a time when they most need it; even as they create the opportunity for better planned and targeted operations by the terrorists.

There has been a constant clamour for a ‘solution’ to the ‘Kashmir issue’. What is obviously missed is the fact that the ‘solution’ is already in play. When a high intensity conflict, with thousands killed each year over the decades is brought to a stage where just 99 lose their lives in a single year, it is not unreasonable to insist that the problem is being ‘resolved’, albeit not abruptly, magically or in the form that some demand. When fatalities rise again, into the three hundreds, this is a cause for concern, even dismay, and it is necessary to make an effort to understand why this has happened – and the answers would be fairly obvious; it is equally necessary to acknowledge that, even at this level, and despite manifest political mischief and administrative incompetence, the levels of violence are a minuscule fraction of what prevailed through the 1990s and early 2000s. The Kashmir issue is being resolved gradually; it is being resolved on the ground, in a slow and continuous struggle between SFs and the terrorists. It is being resolved just as terrorist movements before it have been resolved elsewhere, without – and often despite – the theatrics of high profile political posturing.

*Ajai Sahni

Editor SAIR; Executive Director, ICM & SATP; Publisher & Editor, Faultlines