Morocco: Land Of Tolerance, Togetherness And Harmony – Analysis

Morocco is a country that is very rich of its cultural and linguistic diversity. But is it truly a multicultural society? Can one say that the average Moroccan has the reflex of multiculturalism? What is certain, however, is that Morocco is a haven for tolerance and a high place for accepting the other in his difference and “otherness”. These two very important concepts, nowadays, are part of the Moroccan genetic code.

Nevertheless, because of terrorism, violence, xenophobia and hate that are rampant in today’s world, Moroccan multiculturalism is an example to follow, a case to study, to make discover and to, duly, propagate worldwide in a convincing pedagogic fashion, at a time when hate and racism are more present and strong in minds, hearts and streets.

Morocco has, duly, adopted, today, dynamic multiculturalism. Dynamic multiculturalism is a non-exclusive cultural approach that allows a specific culture to adopt the input of another one, digesting and assimilating the said input in an ensemble where the incoming cultural genre stays easily identifiable while being part of the mother culture fully.

Crossroad country

Morocco is a crossroad country, a country where different cultures, civilizations, languages, beliefs and religions meet and coexist in total harmony. It has been this way since the dawn of times.

The country distinguishes itself by Amazigh, Arab, Jewish, Mediterranean and African cultural influences that Moroccan culture is hugely proud of nowadays. To this cultural richness is added an interesting geographical diversity. In fact, Morocco counts various landscapes, from deserts to mountains to fertile plains framed by maritime coasts of 3 500 kilometers long.

At different periods of its millenary history, Morocco was invaded by the Phoenicians, the Carthaginians, the Romans, the Vandals, the Arabs, the Portuguese, the Spanish and the French. Even the Germans, angered by the sharing made during the Algeciras Conference of April 7, 1906, that had placed Morocco under the protection of major European powers (twelve, among which France, United Kingdom, Germany, Spain and Italy) under the guise of reform, modernity and internationalization of the Moroccan economy and did not give Germany any piece of the “Morocco cake”, came off to the Moroccan southern coast to show their dissatisfaction, by bombarding the city of Agadir on July 13, 1911 by one of its infamous gunboats bearing the name of Panther. 1

These multiple forced meetings with other cultures, languages and races have cultivated among Moroccans an advanced taste for the other and his civilization and, by consequence, an aversion for cultural diversity.

So, cultural diversity is not something new for the average Moroccan, but its notion that is well buried in his past, his subconscious and culture. This notion can be easily detected in his daily verbal language, his body linguistic expressions and even his religious beliefs, without forcibly forgetting his material and immaterial patrimony.2

A cultural melting pot

At the northeastern part of the town of Ksar Kabir, that is located at the northwestern part of Morocco, is a tiny village called Tatoft, where resides a religious brotherhood of a singular genre: the Jahjouka 3 of Ahl Srif, a group that practices spiritual trance music that is supposed to cure followers that are possessed by evil spirits, chief among which the jnoun.4

These valiant musicians are descendants of the Sufi saint Sidi Ahmed Cheikh, who apparently came from the Machrek for religious preaching but ended up settling down with the Ahl Srif, arabized Amazigh/Berbers from the Rif, teaching them the virtues of Sufism and the art of using music to cure some psychiatric illnesses and disorders.

Since then, Jahjouka have abandoned agriculture, their old occupation, to give their body and soul to spiritual Sufi music. As a counterpart for that, they get donations of seeds and money from their tribe every year in the summer, for their religious role of keepers of the mausoleum of the said saint and the perpetuation of his ancestral trance music within the region. It is a sort of dime or tithe.

For a lot of Moroccans, the Master Musicians of Jahjouka are vulgar ghayata 5 who wander around the souks to beg to rustic people for money. But, in reality, Jahjouka are more than a group of souk players or weddings, baptisms and circumcisions party musicians, they are an example of cultural diversity in Morocco of past and present.

For some anthropologists, the Jahjouka 6 are perpetuating pre-Islamic traditions that date from the time of the Roman empire, such as the annual fecundity rites of the agricultural calendar.

For others, the ghayata of this group reminds them of the ancient divinity Pan and of his aversion for sex and, consequently, abundance and fecundity. Indeed, in ancient Greek religion and mythology, Pan is the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, nature of mountain wilds, rustic music and impromptus, and companion of the nymphs. He has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a faun or satyr.

For the ethnomusicologists, this group perpetuates a unique millenary music.

The Master Musicians of Jahjouka were revealed to the public in 1968 by Brian Jones, the star guitarist of the “Rolling Stones”, who recorded the compositions of their ghaytas in an album titled “Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka.” Many other artists, such as Jimmy Page, Ornette Coleman 7 and Peter Gabriel have called on them for the originality of their music. The group had, also, an influence on the poets and the writers of the “Beat Generation,” such as Williams Burroughs and Paul Bowles, who met them in Tangier. These Moroccan musicians, also, appeared in the movie “The Sheltering Sky” by Bernardo Bertolucci, after a suggestion from Bowles.

What is important for the Jahjouka, more than other musicians of the same genre is that this group has successfully assimilated cultural diversity in their musical, cultural and spiritual traditions. Jahjoukas 8 are adepts of Sufi music, a music that is supposed to free the soul of its corporal envelope and allow it to overtly communicate with others. Thereby, their music is in reality a music that promotes dialogue with others. Proof is that famous musicians of international renown such as Ravi Shankar, Randy Weston, Ornette Coleman and many others went to their village to meet them and appreciate with their own eyes and ears their ancestral art.

The Jahjouka are, also known for their musical prowess in playing the oboe (ghayta), known as “circular breathing,” a natural acquired gift that allows them to play air instruments for hours on end without tiring.

The success of the Jahjouka’s 9 tradition resides in the fact that their music, their trances and their religious practices have succeeded in a remarkable way to highlight the fraternity between men and the concordance of cultures instead of their discordance.

The Boujloudia is a party successfully celebrated by the Jahjouka every year in their village, during the sheep festival, Aïd al-Adha. This celebration of trance music, of dance and of theatrical representation celebrates fecundity, but it is, also, a party to thank God of his generosity towards man. The boujloudya is in fact a meeting point between Christian religion, with its concepts of celibacy and purity of the soul, and of Muslim religion, with its asceticism, its sense of sacrifice and of divine benediction (baraka) mingled with a substratum of pagan spirituality common around the Mediterranean Sea.

In reality, the practice of boujloudya dates back to immemorial times in the Mediterranean basin. The boujloudya finds its origin in Greek mythology with the god Pan who was the protector of shepherds, herds, and nature. His ardent love, also, earned him the title of divinity of fertility. In many Mediterranean regions, celebrations take place, even nowadays, at the end of the agricultural cycle which are reminiscent of the cycles of fecundity of the god Pan in the past. Pan is celebrated by trance dances and frantic races to fecund nature and human beings for the year to come.

This pagan practice was introduced in ancient Morocco by the Romans. In their mythology, the name of this god was Lupercus. Since, this practice is fully immersed in popular Moroccan culture, especially among the rural population, which practices agriculture for its subsistence.

What is interesting is that the temper and the philosophy of the average Moroccan throughout history is his open-mindedness towards the other and his culture even if this culture is in contradiction with his beliefs.

By nature, the Moroccan individual does not reject anything that comes from elsewhere, he tries instead to assimilate it by his own means and in his own context so that it does not appear to clash with his faith and tradition. In reality, it is a big capacity of adaptation with the other and his acceptance: a vivid illustration of the gift of dynamic multiculturalism.

When Sidi Ahmed Sheikh, the famous Sufi, who came from the east, arrived in the Tatoft locality of northern Morocco in the 16th century, he was subjugated by the beauty of the region and the friendship of its inhabitants, who were, predominantly, Amazigh/Berber people Arabized over centuries. He taught them the Islamic religion, and while doing so, he understood that they had a love and a gift for music and that they were celebrating pagan rituals by the end of summer. As a good Sufi, infatuated by open-mindedness and soul purity, he assimilated these practices into Islam and so the celebration of the rite of fecundity was moved on to the Hegira Muslim calendar to coincide with the sheep (sacrifice) festival.

There, the celebration was called boujloudya or boujloud in Arabic and bou-irmawen/ilmawen or bou-isrikhen/islikhen in Tamazight, because the principal character of the rite was wearing the skins of the sacrificed sheep.

Another principal character of the practice is no other than the beautiful village virgin that the god Pan tries to soften up to benefit from her sexual favors to fecundate her and fecund nature by the same mean. In the Islamized tradition of the rite, this woman is called Aicha l-Hamqa (Aicha the crazy) to minimize the rite and make it acceptable towards the shari’a and blame this illegal sexual act on her craziness, and show that it is not a practice acceptable in the Muslim tradition.

This practice has been immortalized in the work of William Shakespeare (1564-1616) Julius Caesar, written in 1606. In fact, in the First Act of the Second Scene, Jules Cesar asked Antoine, who was prepping for a religious race to touch the hand of Calprunia, his sterile wife, to have heirs for his vast empire. 10

Languages of expression

A lot of people visiting Morocco often wonder about the reasons for the easy way the Moroccans learn languages. They ask themselves: is it because of physiologic, linguistic, cultural reasons or other?

The reality is that if Moroccans show a baffling easiness to learn languages, this is due mostly to their innate cultural disposition to get to know the other better by the mean of a limpid and direct communication.

Communicating directly allows people to better catch the mood, the nuances, the respective aspirations of the other and to better understand his humanity. In interpreting, a lot of these subtleties are lost or are distorted in such a way that misinterpretations can involuntarily occur in communication.

Douglas Porch, an American historian tells in his book “The Conquest of Morocco” 11 the voluntary and involuntary slips of interpreting. He reports that at the beginning of the 20th century, Tangier, which practically was the only Moroccan city open to strangers along with Mogador (Essaouira), attracted a lot of visitors from the West in need of adventure, fortune, a change of scenery and other reasons. One of these picturesque characters was no other than a priest, who came to convert Muslims to Christianity. Around him, a dense circle of people was formed, seemingly absorbed and captivated by his preaching, relayed by a native interpreter perched on a stool. The secret of this avid interest for the preaching by all these Moor followers resided in the fact that the Moor interpreter, instead of translating the evangelic message of the priest, allowed himself to recount to the onlookers the fantastic and captivating stories of the tales of the Arabian Nights in the pure tradition of the Moroccan street art of halqa. 12

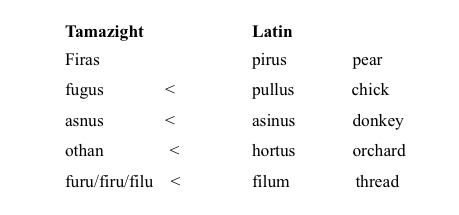

Because of its location, Morocco has always been a crossroad country, it was and still is a real linguistic and cultural melting pot. From the north came the languages of the conquerors, which the Moroccan had learned to better communicate with them. Indelible traces of these civilizations still exist in national languages such as today’s Amazigh in its version from the Rif: 13

Added to the linguistic remains that are always present in the Moroccan spoken languages, the Romans had left entire cities in Morocco, such as Volubilis, Lixus and others and a multitude of traditions still strong in local cultures.

Added to the linguistic remains that are always present in the Moroccan spoken languages, the Romans had left entire cities in Morocco, such as Volubilis, Lixus and others and a multitude of traditions still strong in local cultures.

For the Roman era specialists, the easy maritime traffic in the warm waters of the Mediterranean Sea, commonly called mare nostrum (our sea) by the Romans, contributed a lot to the exchanges between the different cultures: 14

“The imperial era is, without doubt, the apogee of the maritime life in antique Mediterranean, in regards to the traffic intensity, the number of boats and of passengers, and the volume of merchandise. The political unification of the Mediterranean world under Rome authority and the peace that had resulted for all neighborhood countries gave to the circulation of goods and of people a freedom, an ease and a safety never known before.”

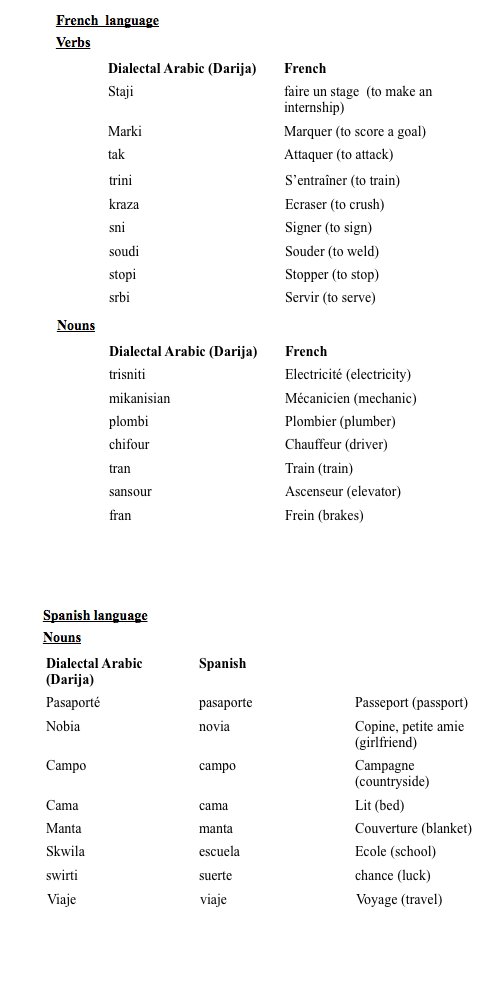

But, in addition to the Romans, also, came the Vandals, the Portuguese, the Spanish, the English, the Italians and the French and they all left linguistic marks of their visit. Today, these traces are audible in Moroccan Arabic, 15 and, as such, these multiple borrowings are of 19% mark from French language throughout the territory, and 12% mark from Spanish in the north and in the Moroccan Sahara.

Edifying examples of these borrowings due to commercial exchanges and, also, to cultural clashes and frictions are as follow: Nowadays, English is slowly but surely planting its roots in the linguistic Moroccan landscape and in the Moroccan customs thanks to immigration, Internet and art (cinema, music, etc.). Thus, we can see shops with English names such as: Best Shop, My Tailor, Nice and Easy, Baby Shop, etc. and at the same time, in young people’s language: cool, friend, girlfriend, baby, black, clean, groove, etc.

Nowadays, English is slowly but surely planting its roots in the linguistic Moroccan landscape and in the Moroccan customs thanks to immigration, Internet and art (cinema, music, etc.). Thus, we can see shops with English names such as: Best Shop, My Tailor, Nice and Easy, Baby Shop, etc. and at the same time, in young people’s language: cool, friend, girlfriend, baby, black, clean, groove, etc.

In parallel, Anglo-Saxon celebrations of commercial order gradually implanted themselves in the Moroccan cultural landscape during the beginning of the third millennium, such as : Halloween, a celebration of ghosts and specters and Valentine Day, a celebration of love and affection. These modern mercantile rites have, in principle, no place in Moroccan culture because they convey a philosophy that is contrary to Islamic ethics.16 But, in any case, these practices have settled comfortably in the traditions of today’s Moroccans, who, thanks to the digital revolution, want to look, act and feel American in idiom use and way of life.

Endnotes:

1. For more details, see « Chronique de la Conférence », MEE, TR XX/38, Caisse 334.

2. For people from the Rif, aghrib, “the other, the stranger, the traveler, etc.” does not only benefit from the protection of the clan or of the tribe, but, also, benefits from the right to work and own a house on its territory. This is part of the honor code of each clan and tribal entity whose bards sing, with pride, during festivities such as marriages, circumcisions and baptisms.

3. Cf . M. Chtatou ; « The Magical World of the Master Musicians of Jahjouka » in BRISMES Proceedings of the 1986 Conference on Middle Eastern Studies. Ed. L.D. Lanthan. Oxford : British Society of Middle Eastern Studies, 1968.

4. Jnoun, pl. jenn : evil spirits in the oral cultural and popular Moroccan tradition.

5. Ghayta, air musical instrument. Player usually called ghayat.

6. Cf. S. Davis. Jajouka Rolling Stone : a Fable of Gods and Heroes. New York : Random House, 1993. In this novel, the writer narrates the visit of a National Geographic journalist to Jahjouka and his efforts to publish an article on their music and their way of living. He, also, talks of the development of the group’s international career: visit of Brian Jones, recording with Randy Weston. He, also, covers the musical and theatrical tradition of Jahjouka. The book deals with the boujloudya celebration and its meaning, the royal decree officially establishing the group, the never-ending visits of foreign musicians, homosexuality and marijuana. He ends the work with interviews of multiples Jahjouka « movers » such as: Brion Gysin, William Burroughs, Paul Bowles, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger.

7. Cf. R. Williams. « Ornette and the Pipes of Jahjouka » in Melody Maker, March 17, 1973, p. 22.

8. Cf. P. D. Schuyler. « The Master Musicians of Jahjouka » in Natural History 92 :10, pp. 60-69.

9. Cf. K. Sabin. « Moroccan Music : The « Foreign » and the « Familiar » : an Annotated Bibliography and Discography », ( term paper for Popular Culture in the Middle East (SOCIO 470), Spring 2000.) http://users.ox.ac.uk/~sant1114/MoroccanMusic.htm #Jahjouka

10.

Caesar:

Calpurnia!

Calpurnia:

Here, my Lord

Caesar:

Stand you directly in Antonius way,

When he doth run his course. Antonius!

Antony:

Caesar, my Lord?

Caesar:

Forget not in your speed, Antonius

To touch Calpurnia ; for our elderly say,

The barren, touched in the holy chase

Shake off their sterile.

11. In this highly-interesting book, the author describes the town of Tangier at the beginning of the 20th century. Cf. D. Porch. The Conquest of Morocco. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1983. P. 14.

12. halqa: street, market or public places musical theater.

13. Cf. M. Chtatou. “ Aspects of the Phonology of the Berber Dialect of the Rif”. Doctoral thesis from SOAS, University of London, 1982, p.82. Cf. , also, M. Chtatou. Central-Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean Region: Similarities and Differences. (Athens: Halki International Seminars 1997 (Occasional Papers. OP97.10)), p. 4.

14. Cf. Encyclopaedia Universalis, Vol. 10. Paris: Encyclopaedia Universalis, France, 1980, p.729Cf.

15. Cf. M. Chtatou. “Language Policy in Morocco”. Morocco: Occasional Papers No. 1, 1994, pp. 43-62.

16. Moreover, the Islamists strongly advocate, in their ideological jargon, the re-Islamization of society, and one of their multiple aims is none other than to rid Muslim society of the “defilements” of Western civilization such as the pagan and Christian practices which have become practices with a purely commercial but decadent aim.

The mythical Moroccan Khamsa : living together in total harmony and peace