Toleration Does Not Require Calling Evil Good – OpEd

By MISES

By Zachary Yost*

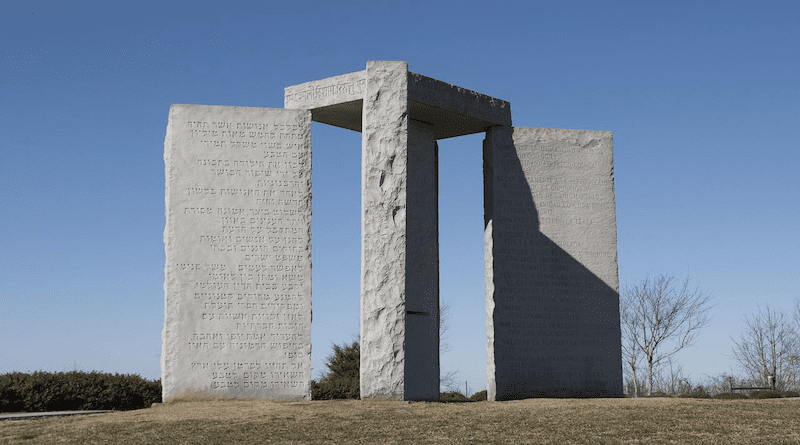

In the early morning of July 6, an explosion damaged the Georgia Guidestones. Because of the damage, the rest of the monument was demolished for safety reasons. At this writing, it seems that the explosion was the result of purposeful sabotage.

Writing at Marginal Revolution, Alex Tabarrok compares the willful destruction of the Georgia monument to the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in 2001. The massive buddhas carved into the mountainside were over a millennium old and were a reminder of the once flourishing Buddhist culture in south-central Asia and of the fascinating fusion of Buddhist and Greek culture that occurred as a result of the conquests of Alexander the Great. The destruction of these statues, and the beauty and shared eternal truths that they represented, are a loss to all of humanity.

However, the same cannot be said of the loss of the Georgia Guidestones, and it is an error, and in fact an affront, to compare the two, as Tabarrok has done. This is for the simple reason that while the Bamiyan Buddhas were objectively good, the Georgia Guidestones were objectively bad.

To be clear, it is undoubtedly wrong to begin terror bombing monuments because one disagrees with their message. But opposition to bombing things does not mean that one must embrace whatever has been bombed or recognize it as good.

This is especially true in the case of the guidestones, which were erected by anonymous donors in 1980. The stones listed ten principles for humanity in multiple languages. The first principle calls for the maintenance of the human population below five hundred million, a level that it has not been at since approximately 1600 and that would require decreasing the current population by over seven billion.

Other principles included “guid[ing] reproduction wisely” in order to improve “fitness and diversity,” the adoption of a new global language, the institution of a world court, and a call for humans to “be not a cancer on the Earth.”

Such “principles” are obviously beyond creepy to a regular person but throughout the twentieth century have greatly appealed to some elites, who simply changed their branding from promoting eugenics to promoting “population control” after eugenics became a dirty word.

While it would make sense to be concerned about a politically motivated bombing, it is not clear why Tabbarok would be “saddened and disturbed” by the destruction of an antihuman monument that advocates for a literal eugenic breeding program, especially because he obviously does not share those values, as evidenced by his work.

There seems to be frequent confusion among many libertarians and liberals between arguing for the legal tolerance of things and defending said things as necessarily being right and good.

From a Misesian liberal perspective, it was wrong to bomb the monument because terrorist bombings undermine the social order upon which all of civilized life depends. The alternative to a liberal order where we hash differences out through the political process is a Hobbesian world, where the strong rule because they managed to crush and destroy anyone who opposes them. To jaw-jaw is better than to war-war, as the saying goes.

The fact that liberals and libertarians oppose terror campaigns and endorse peaceful social coexistence does not mean that we endorse what is tolerated, nor does it require that we call evil good and good evil.

In his recent talk at the Austrian Economics Research Conference, Jason Jewell had some useful insights into the relationship between objective ontological value and subjective value, which has proven to often be a stumbling block for libertarians, including some Austrians who embrace a radical subjectivism, like Israel Kirzner and Ludwig Lachmann (in contrast to Ludwig von Mises and Murray N. Rothbard).

While the lecture is full of too many insightful points to explore in depth here, Jewell begins his talk by drawing upon C.S. Lewis’s important work The Abolition of Man. In this book, Lewis defended natural law, which he calls “the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are.” Lewis points out that this central idea exists in almost all historical times and cultures and labels it simply as “the Tao.”

As Jewell explains, even Misesian consequentialism, which rejects natural law, is ultimately grounded on the idea of there being an objective good—i.e., social utility. Similarly, he points out that Rothbard was quite amenable to objective value, especially due to his appreciation for Aristotle and natural law, which is the first thing he discusses in Ethics of Liberty.

All this is to say that holding a belief in liberal toleration and subjective economic value does not require one to equate ancient works of art that enrich humanity and literal monuments to evil. The loss of the Bamiyan Buddhas is a great loss to all of humanity because they were objectively good. While political bombings are bad and antiliberal, the loss of the Georgia Guidestones is nothing to mourn in and of itself because advocating for eugenics is objectively bad.

*About the author: Zachary Yost is a freelance writer and Mises U alum. You can subscribe to his newsletter here.

Source: This article was published by the MISES Institute