Brazil: Police Killings At Record High In Rio, Says HRW

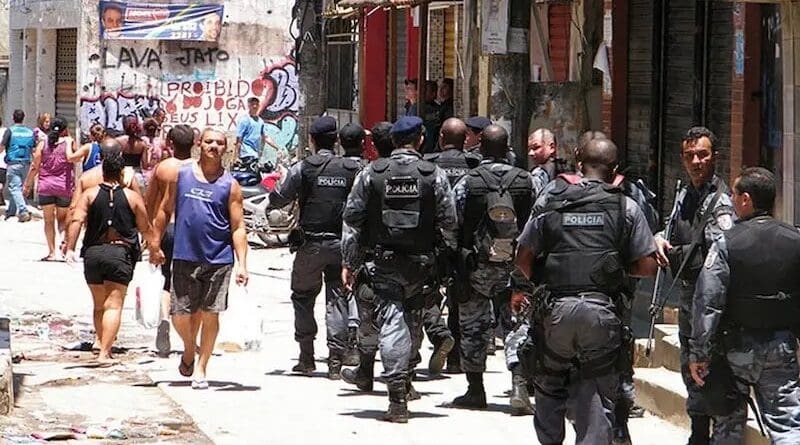

Federal and state authorities should take urgent measures to curb police killings in Rio de Janeiro state, which have reached a record high, Human Rights Watch said.

From January through November, 2018, police killed 1,444 people in Rio de Janeiro state, according to the Public Security Institute (ISP, in the Portuguese acronym), a state agency. That means that Rio will finish the year with the highest number of police killings since the state started collecting that data in 1998. The previous record was 1,330 in 2007.

“Military-style security operations that leave a trail of death in poor neighborhoods do not enhance public security,” said Daniel Wilkinson, Americas managing director at Human Rights Watch. “On the contrary, these killings make communities fear the police and much less likely to collaborate with the police in the fight against crime.”

While Rio police sometimes kill people in legitimate self-defense, research from Human Rights Watch and other groups shows that many killings are, in reality, extrajudicial executions.

Abuses by police make members of the affected communities less likely to report crime, to assist with criminal investigations, and to stand witness at trial, Human Rights Watch said.

Extrajudicial killings by some officers also put the lives of other officers in danger, by antagonizing law-abiding citizens of the communities they patrol. In addition, gang members are less likely to surrender peacefully to police when cornered if they believe they will be executed.

In January, in response to a Human Rights Watch report about police killings, Rio de Janeiro’s Secretariat of Public Security said that the military police had established a goal of reducing the number of police killings in 2018 by at least 20 percent.

In reality, the number of police killings from January through November was 39% higher than the same period in 2017. In addition, news media reported nine killings of Rio de Janeiro residents by army personnel deployed in public security operations in 2018. Those killings are not included in the official state statistics because they are not investigated by civil police but rather by the Armed Forces themselves.

From January through November, 31 police officers were killed while on duty, the same number as the same period in 2017, said ISP, which does not provide data about officers killed off duty. At least three soldiers were also killed while on duty.

On February 16, the outgoing Brazilian president, Michael Temer, put public security and prisons in Rio de Janeiro in the hands of the army. In June, General Walter Braga Netto, the commander in charge of public security operations in Rio, released a detailed “strategic plan” with the overall goal of reducing crime and increasing the “sense of security” of the population. The plan made no mention of the military police’s promise at the beginning of the year to lower police killings and said nothing about punishing officers who committed abuses.

Although violent deaths fluctuated from month to month, the overall number from March – the first full month that the army was in charge of public security in Rio – through November was virtually the same as in the same period in 2017.

From March through November, police killings went up 38 percent compared with the same period in 2017, ISP data show.

In March, an elite squad of military police killed eight people in a raid in Rocinha neighborhood; and another six in May during a raid in Cidade de Deus.

In June, police allegedly opened fire from a helicopter into Rio’s heavily-populated Maré neighborhood. Police never confirmed they opened fire from the air, but residents counted more than a hundred bullet marks on the ground. Seven people died in the raid, including 14-year-old Marcos Vinícius da Silva, who was on his way to school. Before he died, da Silva told his mother the bullet that hit him came from a police armored vehicle. “Didn’t they see my school uniform?” he asked her, his mother later said. In a report to prosecutors, the civil police called the operation “a great success.”

Instead of seeing the excessive use of force by police as a problem, President-elect Jair Bolsonaro has essentially promised to give “carte blanche” to police to kill even more people. Rio de Janeiro´s new governor, Wilson Witzel, who belongs to Bolsonaro´s Social Liberal party, has said that police should shoot to kill, without warning, anyone carrying an assault rifle — including using snipers and drones — even if the person is not threatening anyone. International human rights standards only allow police to deliberately kill people when necessary to protect their own lives or the lives of others.

“The mission of the police is to protect people, including those who live in poor neighborhoods,” Wilkinson said. “The excessive use of lethal force puts everyone at risk.”