The Old Is Dying And The New Cannot Be Born: A Power Audit Of EU-Russia Relations – Analysis

By ECFR

By Kadri Liik*

Introduction

With the Russian army losing ground in Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin’s hopes for victory must lie with winter heat and cold: that his military strikes on Ukraine will demoralise its soldiers and freeze civilians into submission; that energy shortages and price hikes in the West will weaken international resolve to support Kyiv. From Putin’s point of view, only a weaker West would allow him to emerge victorious – and allow Russia to keep the territorial spoils without long-lasting Western sanctions economically and politically incapacitating the country. This gives Moscow a profound strategic interest in splitting the West.

Putin appears to believe this gamble will pay off. “The ongoing collapse of Western hegemony is irreversible,” he declared in September, adding that the energy shortages suffered by the continent are attributable not to Russia but to Europe’s faulty policies. He later pointed to “the systemic mistakes of [Europe’s] political leaders, the political leadership of your countries – in the energy and food sectors and in monetary policy that led to an unprecedented growth of inflation and a shortage of energy resources”.

In light of this faceoff, to understand the vulnerabilities and the strengths of Europeans’ relationship with Russia, ECFR surveyed decision-makers across the European Union’s 27 member states. Researchers in each country spoke to policymakers and other members of the political class to understand their views and positions on Russia. This paper therefore presents a new ‘power audit’ of European relations with Russia. Its findings confirm that, in a sense, the EU and its member states have reached the same conclusion as Putin on at least one crucial point – that Europeans had let their dependences grow too deep. But cracks in the coalition are few: European unity is highly unlikely to crumble in the face of Russian aggression.

The research reveals that the shock of war has fuelled frantic activity, with governments working round the clock to address the practical aspects of decoupling from Russia, strengthening energy security within the EU, and providing material support to Ukraine. The energy situation in particular caused some significant worry over the summer and autumn, but, rather than result in defeatism (as Moscow may have expected), it prompted a resourceful and creative search for solutions. EU member states’ response has not been to seek ways to restore the status quo ante, but to brave the weather and act. Now, looking back on 2022, European leaders can boast of some notable achievements: their gas storage is full; they have assembled liquefied natural gas terminals in record time; and they have taken steps to alleviate the cost-of-living pressures on their domestic populations and industries. The winter is already a lot less threatening than it appeared just a few months ago.

But the main questions facing Europeans will linger long beyond this season. Russia and the West will remain in an adversarial relationship for some time to come; and EU leaders will need to learn to navigate this new reality. Europeans have no fixed view yet of what the longer-term relationship with Russia should look like, or what model of European order they want to shape. Nor do they yet know how to approach their relationship with China in the global web of power relations, in which Russia holds a central place. They have, however, identified their near-term priorities: addressing their energy dependence and upholding a strict sanctions regime. Such actions contain glimpses of what a stronger and more sovereign Europe looks and acts like. This will not be what Putin had in mind in February 2022 – but the violence he has unleashed may now hasten its entry onto the world stage.

The war

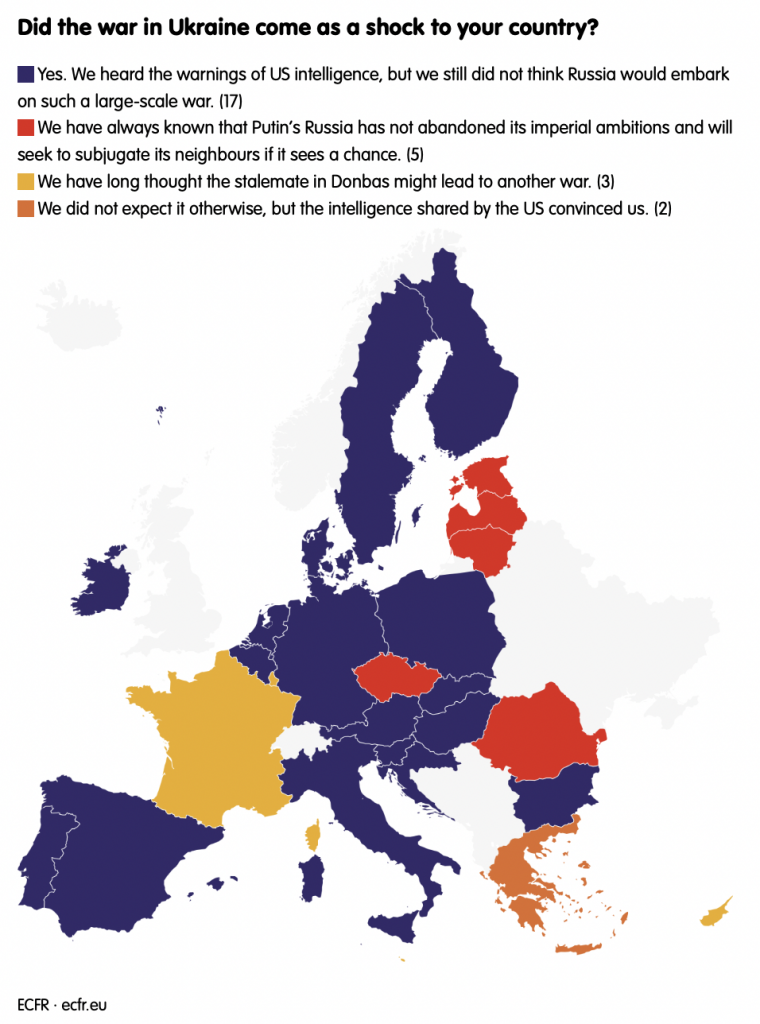

Our research shows that Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine came as a shock to European policymakers. From autumn 2021, US intelligence services had been warning of war, but few Europeans believed that Russia would really embark on such a large-scale attack. The minority who expected war may have been less driven by acute analyses than by a habit to always expect the worst from Russia.

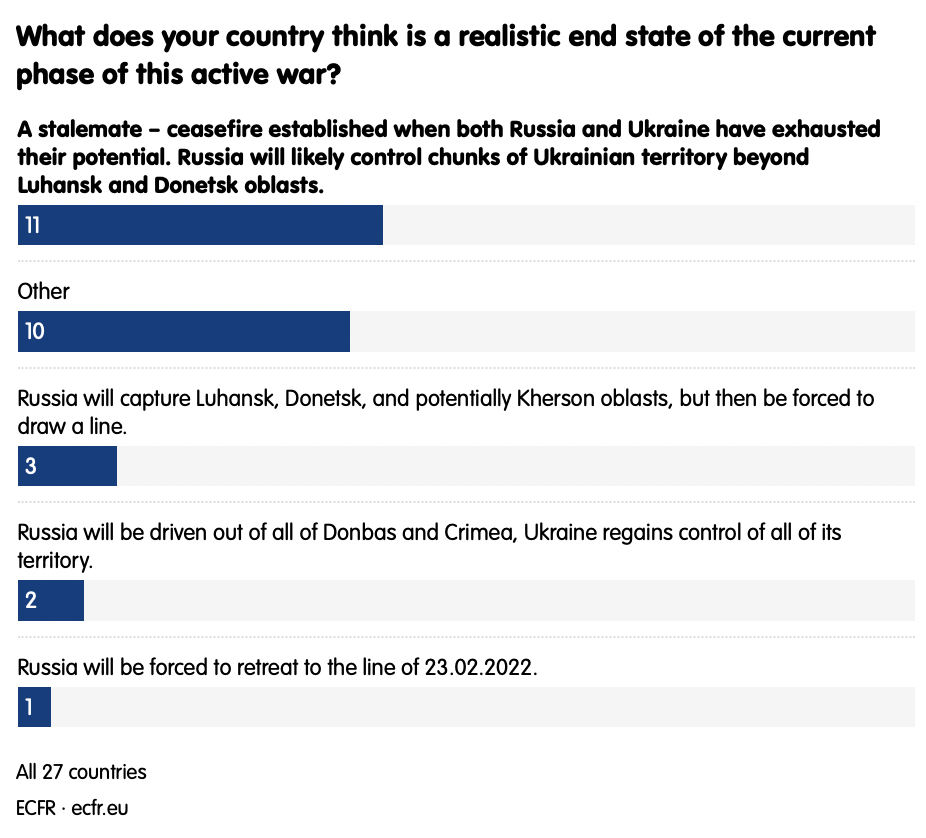

Nearly a year into the conflict, new uncertainties have set in for European policymakers: crucially, the power audit survey finds that they lack any agreed theory of victory. In most capital cities, decision-makers predict a prolonged war that ends with some form of stalemate. Opinion largely expects an impasse in which both Russia and Ukraine exhaust their potential to advance and the frontlines settle somewhere in eastern Ukraine. In just two countries do policymakers say that they believe Ukraine can win by reconquering all of its territory. The research was conducted before Ukraine retook Kherson: the victory there might have caused more to convert to this view, but it is likely that opinion remains downbeat about prospects for a swift and convincing Ukrainian victory.

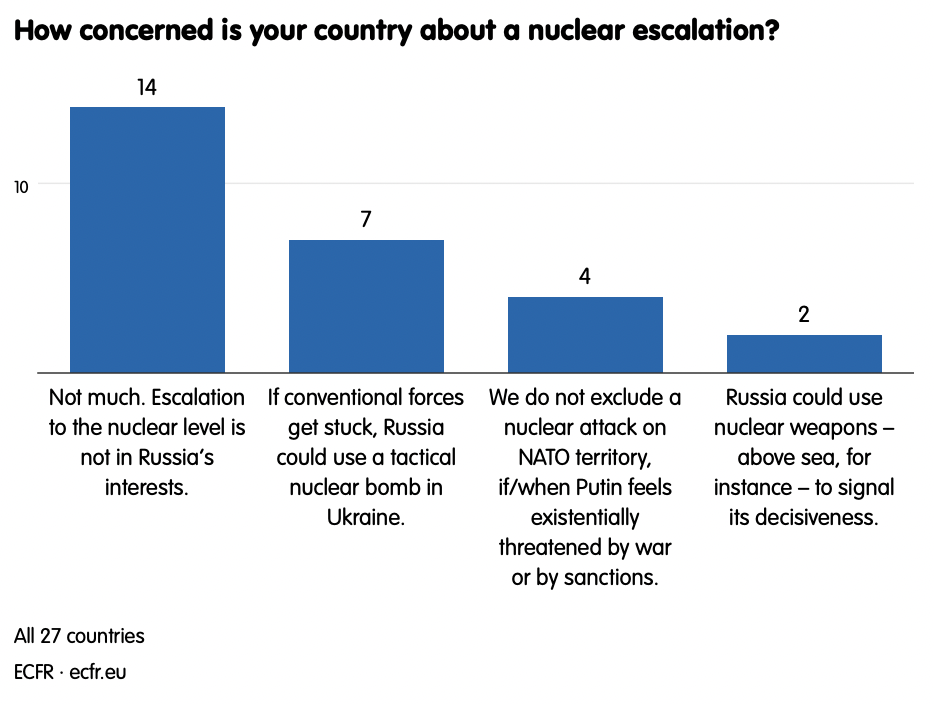

One effect of Ukraine’s advance may be to increase worry in EU capitals about the nuclear dimension of the conflict. The power audit found that policymakers in 14 countries judged a nuclear escalation to be counter to Russia’s interest, while in 7 countries respondents felt that Russia could resort to nuclear weapons if its conventional forces continue to fare poorly. In a further 4, policymakers said they would not rule out a scenario in which Russia launches a nuclear attack on NATO territory if Putin feels existentially threatened. Decision-makers in the EU’s only nuclear power, France, point out that the conflict already has a nuclear dimension, as Russia’s invasion takes place under the umbrella of nuclear deterrence. At the same time, observers in Paris also note that Moscow’s actions so far remain in line with Russia’s nuclear doctrine. They believe that the nuclear threat remains distant unless and until Ukraine starts to seriously threaten Crimea.

One researcher admitted that their small, southern EU state lacks the expertise to reliably evaluate nuclear risks – which will likely be the case in many other member states too. This, in turn, creates a risk of Europe’s nuclear debate becoming a faith-based argument, with governments using the nuclear issue to justify their established views. One can already see how the Baltic states, for instance, believe that the Russian nuclear threat is merely a form of blackmail, while nuclear-averse Germany gives much greater credence to the prospect of a nuclear attack. Such cleavages could under some circumstances become a problem, were it not the case that on all nuclear matters the United States will probably have the lead role.

Respondents in a number of countries, mostly in southern Europe, quietly admit that they would like to see a negotiated settlement, even if this involved territorial concessions by Ukraine. This appears to confirm a division into ‘peace’ and ‘justice’ camps – countries that prioritise a cessation of fighting versus those who want to see Russia punished – but it has not led to a split. This is likely because, so far, public and policymakers alike view Ukraine’s response as purely defensive and therefore inevitable, and preconditions for negotiations absent. But this could change, if the nuclear dimension of the war became more prominent, or if Ukraine started taking back territory it lost to Russia in 2014. The survey suggests that if and when Ukrainian military enters territory that Russia has controlled since 2014, the question “what now” would become more pertinent again.

Still, the public position in almost all EU member states is that only Ukraine can decide whether to negotiate. Few policymakers believe that outsiders could play a significant mediator role. Some point to Turkey as a potential intermediary, but most also make clear that, while Turkey’s role can be valuable on important but limited matters such as overseeing the grain export deal, it appears to be beyond its powers to bring the conflict to an end.

Policymakers across the EU also harbour no illusions about the EU’s own mediation capacity. Early on in the war, the question of outreach to Putin was an issue that divided Europeans – eastern Europeans were furiously critical of President Emmanuel Macron’s and Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s phone calls to Moscow, assuming that Putin would regard these as a sign that Russia was not isolated. These differences were reflected in the survey, and the passions around them still flare up every now and then. Such was the case recently when Macron stated that the future political order needs to involve “security guarantees to Russia”, he was widely criticised in eastern European countries. Overall, though, it seems to be increasingly evident that neither diplomatic engagement nor a sense of isolation from the West will, at this point, compel Putin to roll back his war. Therefore, phone calls to the Kremlin – which in any case are now few and far between – are probably harmless, if not pointless.

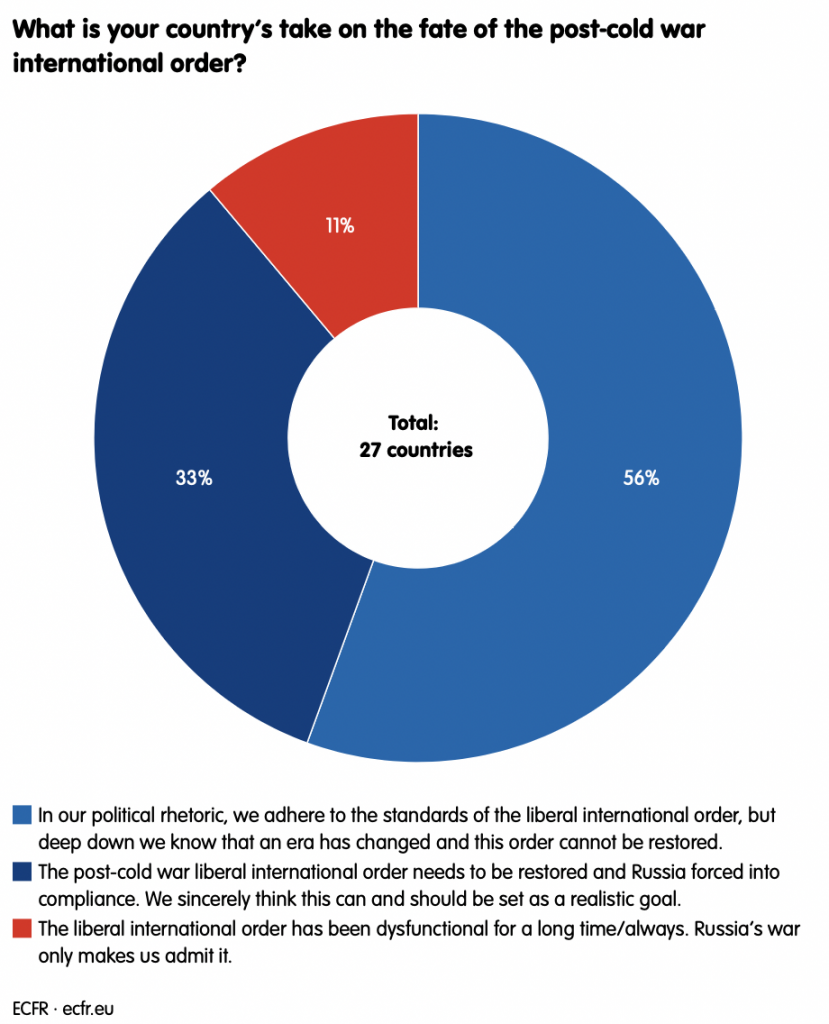

The change

It is hard to overstate how profoundly this war has changed the way Europeans see the world, as well as the way they view their relationship with Russia. Respondents are clear in their belief that the post-cold war liberal international order, as well as the European order as envisaged in the 1990 Paris Charter – of a common European home, of a continent “whole and free” – is dead and buried. In more than half of EU states, policymakers largely regard the old order as beyond restoration. And, while references to the ‘rules-based order’ remain ubiquitous in European leaders’ political statements, these now probably amount to little more than shorthand phrases for demanding accountability and rejecting impunity.

This shift may have been the most dramatic for those countries that had invested the most in their relationship with Russia. Germany features prominently here: ‘rapprochement through interdependence’ was long the guiding motif of Berlin’s Russia policy. German respondents admit that the annexation of Crimea caused a shock but that the true turning point came only in 2022. Cooperation with Russia is now entirely off the agenda. Germany is instead seeking to insulate itself against Russia, particularly by unlocking new sources of energy supply. Another example of profound change is Finland, which over many decades invested considerable diplomatic capital in cohabiting with Russia and pursued profitable business ties. Yet, Finnish policymakers are now fully behind its decision to join NATO.

In contrast, the Baltic states and Poland have undergone no rethink because their political mainstreams have always been highly suspicious of Putin’s Russia. Indeed, they have long considered other countries naive for their attempts at outreach. Nonetheless, they have experienced a major change to everyday life. These countries are now frontline states dealing first hand with the impacts of the war: sending arms to Ukraine, receiving refugees, handling inflation, and negotiating increases in defence budgets as well as allied presence. The power audit confirms that their decision-makers view a direct Russian attack as a real possibility.

The case of Italy is instructive in terms of where Russia has lost some of the ‘swing’ opinion it might once have hoped to win over. Rome is traditionally the capital friendliest to Russian narratives, and Italy had strong commercial connections with Russia. But after February 2022, the then-prime minister, Mario Draghi, appears to have undergone a personal profound rethink: the formerly dialogue-minded politician, who had previously sought to reconcile Russia with Europe, was forced to admit that talking with Putin had failed to have any impact on the Russian army’s behaviour on the ground: “What do we want to call Bucha’s horror if not war crimes,” he said in an interview. Ultimately, Draghi became a strong supporter of Ukraine, backing a price cap on Russian hydrocarbons and pushing Italy well beyond the comfort zone of public opinion in supporting Kyiv. While Italy’s military support has been limited, Draghi became a leading advocate of offering Ukraine the status of candidate for EU membership. And his stance appears to have outlived his premiership: coupled with Italy’s traditional desire to stay on good terms with the US, it remains the foundation of Italy’s position under his successor, Giorgia Meloni.

And Italy is not the only example of a potential swing state turning away from Russia. The survey shows that the Kremlin had already lost the sympathetic ear of many capitals before February 2022. For example, Dutch respondents cite the downing of MH17 as a turning point. Czech observers point out that explosions at the Vrbetice arms depot in 2014 – executed, as later became evident, by agents from the GRU, Russia’s foreign military intelligence agency – left their imprint. Ireland was disturbed by cyber attacks and Russian war games in its exclusive economic zone in January 2022. In 2018, Greece expelled Russian diplomats for meddling in its internal affairs, following Russian attempts to stage a coup in Northern Macedonia. Spanish policymakers note the humiliating treatment meted out to EU high representative, Josep Borrell, while in Moscow in February 2021 – this was on full display in his native Spain, whose government will have heard loud and clear his later assessment that Russia had become a threat.

In early 2022 Moscow may have hoped to get away with a short, victorious war, with the EU’s business interests lobbying to prevent severe sanctions. But goodwill across the EU was already stretched thinly before it embarked on a war that failed to be either short or victorious.

Leaderless unity

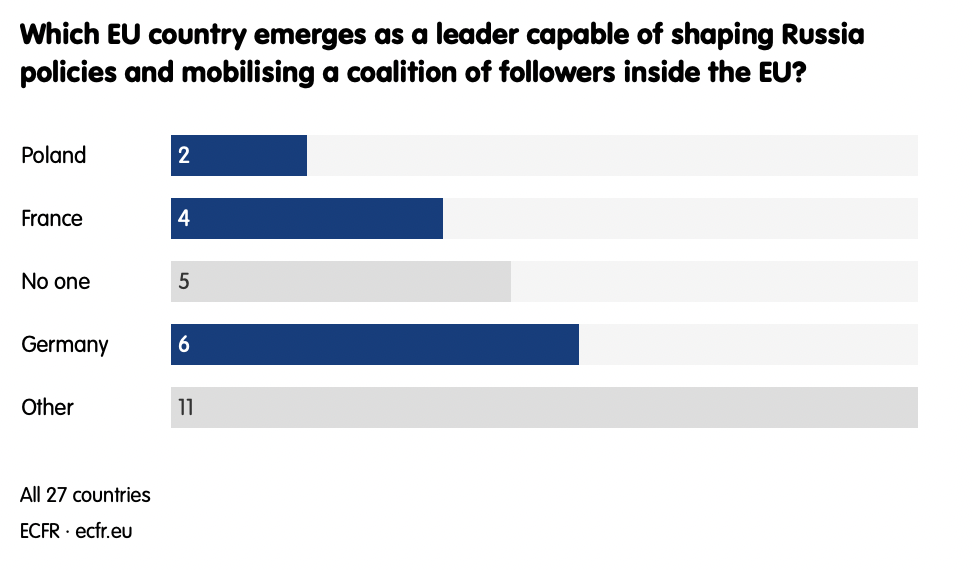

In contrast with the period after the annexation of Crimea, when Germany was the leader that sought to bring other EU states around a joint position, the EU’s current unity now appears leaderless. No country emerges as a focal point: while some respondents say that Germany, France, or Poland play this part, none has a dominant role in driving the EU’s Russia policy. Indeed, a picture of decentralised decision-forming emerges: policymakers recount that they regularly consult among like-minded states, often with a geographical focus. For example, the Nordic and Baltic states stay in regular touch on Russia-related matters. Similarly, Mediterranean states also compare notes. Interestingly, though, there are also networks emerging that extend out of the regional context: the Czech Republic and Slovakia seem to have been particularly good at fostering partnerships that are not obvious at first sight. In many smaller countries further away from Russia and Ukraine, such as Portugal and Ireland, policymakers say that they are likely to fall in with the EU mainstream, regardless of how its positions emerge. Even in countries that might have been expected to be friendlier to Russia, Cyprus and Malta among them, elite opinion swings behind backing EU positions.

The leaderless nature of the EU’s unity could work both ways. On the one hand, the absence of a clear centre of gravity obliges all countries to work harder to ensure they establish common positions. On the other hand, Europeans have in fact largely followed Washington’s lead on several crucial matters, such as arms deliveries to Ukraine or whether to speak directly to Russian senior figures. Should a US president less engaged in, or even hostile towards, Ukraine come to power in 2025, Europe could quickly discover the downsides of leaderlessness.

Also in contrast with the period after 2014 – when Europe linked its sanctions on Russia to the fulfilment of the Minsk agreements – there is now very little discussion among those devising Russia policy about whether sanctions work or not. The only outlier is Hungary, whose government would like to see the sanctions dropped. The question of the efficacy of sanctions still crops up in some media outlets or is voiced by Russia-friendly former politicians – in countries such as Italy and France, for example – or among political opposition in countries such as Bulgaria whose historically close relationship with Russia still finds significant political expression in parliament. But power audit research reveals that opinion in no fewer than 19 capitals is strongly behind the measures, viewing sanctions as robust, sustainable, and necessary to weaken Russia’s war efforts. In 5 other capitals, policymakers state they would like to see the EU go even further on sanctions.

Bickering and muddling through

This is not to say that the mood in the EU capitals is one of cloudless unity and harmonious solidarity. As demonstrated already by the onset of covid-19 in 2020, a sudden existential crisis can put EU solidarity under pressure. It nurtures national approaches and undermines common policies. This is also true of Europeans’ response to the war in 2022, with countries scrambling to secure their energy supplies initially with little thought for their neighbours’ needs. This has created some cleavages, such as the Franco-German spat over how to deal with energy supplies, subsidies, and China policy.

The power audit survey also shows expected levels of finger-pointing, again much of it directed at Germany. Berlin’s energy worries have generated some Schadenfreude from different places: southern European respondents have not forgotten the fiscal orthodoxy that Berlin imposed during Europe’s financial crises that saw the south in trouble, while eastern Europeans gleefully point out that they had always warned Berlin against relying on Russian gas. But eastern Europeans’ own double standards also come under scrutiny: “The Baltic states have always demanded that the EU speak with common voice about Russia, but now they have single-handedly destroyed Schengen,” was one how one (eastern European) respondent described the visa ban on Russians spearheaded by the Baltic states.

The rush to secure energy supplies also clashes with the EU’s other declared policies – not least the European Green Deal. In our survey, most respondents remained optimistic about their countries’ capacity to tackle the energy crisis while also maintaining green standards. While this may indeed be the case in the medium and long term – by which time Russia-related energy crises are likely to have actually accelerated the green transition – it is hard not to see an environmental slump happening in the short term, given that Austria, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland, and the Czech Republic have given a new lease on life to coal-fired power stations, with the German Greens, quite strikingly, preferring the use of coal to extending the life of their nuclear power stations.

All of this is also on display to Russian observers looking for clues to what will happen next. But, if any conclude they are witnessing a trend destined to weaken the EU, they will be disappointed. The survey findings make clear that, whatever the differences on details and even policies, these are on a different scale: all are clearly trumped by common interests and support for the overarching strategic need to maintain the EU as a united and coherent actor. And, as concerns the muddling through approach, this, for the time being, takes precedence over due procedures and common policies. Respondents are conscious of this, but it does not worry them too much. They may be aware that, throughout the EU’s history, what starts out as muddling through often later morphs into newly harmonised procedures that provide an established basis for action.

The outlier

The only country that shares almost none of the pan-European sentiment evident in this research is Hungary. Indeed, Hungary largely corresponds to Putin’s view of what a European country true to its interests should look like: putting economic interests before abstract values, prioritising gas trade and links to Russia, subscribing to a great power-centric vision of geopolitics, showing due respect to Moscow, prioritising state sovereignty over human rights and criticising interference from outside, and shunning ‘woke’ views and values in its domestic politics. The prime minister, Viktor Orban, even echoes Putin’s line about the decline of the West and the rise of new powers elsewhere that need to be taken seriously. His government seeks economic benefit through stronger relations with Russia and China.

The survey finds that Hungarian government-affiliated policymakers frame Russia neither as a threat to itself or to Europe. Indeed, Orban subscribes to the view that the West created the conditions for Russia’s war; he also tends to speak of Russia and Ukraine as equal sides in the war, not as aggressor and victim. Hungary has delivered no weapons to Ukraine, and does not allow other countries to use its territory for this purpose. It has continued to invest in its bilateral relationship with Russia, and views maintaining gas imports from Russia as a paramount goal.

Hungary is the only country that vocally opposes the EU’s sanctions on Russia and it has threatened to wield its veto over expanding them. The Hungarian government is unconcerned about Russian information operations or Kremlin narratives. It is also unfazed by the EU’s failure to win over much of the global south to its own position on Russia, or by the question of how to counter both Russia and China – the government’s stance is that the EU has no business opposing either.

However, Hungary’s position should be understood for what it is. Its illiberal rhetoric and emphasis on gas trade are both means to maintain and justify illiberal rule at home. In the EU arena, Hungary makes use of its veto powers to bargain for its own interests. A case in point is Hungary’s recent veto of €18 billion of European aid to Ukraine: although the government denied the issue linkage, this was widely seen as a reply to the European Commission proposing the suspension of structural funds to Hungary following its persistent infringements of the rule of law. As soon as a compromise was found that unlocked some EU funds, Budapest relented and agreed to support the EU’s joint assistance to Ukraine.

It is important to note what Hungary is not doing: it is not attempting to alter the EU’s core positions in any meaningful way. It is not searching for like-minded countries to form coalitions to change EU policy on Russia. In fact, the opposite is true, and even Budapest’s former partnership with Law and Justice-led Poland has effectively crumbled under the weight of Russia’s war. Observers in Budapest admit that Hungary is isolated in the EU’s Russia discussions and can do little to challenge the wider consensus – nor does it necessarily want this, its agenda being mainly driven by opportunism. So, if Putin thinks that politicians such as Orban will change European policy more to Moscow’s liking, he may be in for a long wait.

The question of Russia

The power audit confirms that European policymakers, almost to a person, regard Russia as the sole culprit in the war. The sort of argument floated by US ‘realist’ thinkers such as John Mearsheimer – who see NATO expansion and Western dominance as having left Russia with no choice but to attack – have found no traction whatsoever among decision-makers across the EU. Only Orban shares some of that sentiment, when he suggests that the West’s refusal to negotiate with Russia about Ukraine’s NATO membership compelled Russia to defend its interests with force.

This is not to say that the West is viewed as flawless. Europeans admit they have made their share of mistakes: French respondents cite the 2008 NATO Bucharest declaration, which promised Ukraine NATO membership without providing the means to achieve it. They also point to the Minsk process, which in the end frustrated both Ukraine and Russia and may have contributed to escalation. Polish respondents, meanwhile, see Germany’s energy trade with Russia as a factor that enabled the war. However, none views these Western (mis)deeds as something that could explain, still less excuse, what has happened: this is Russia’s war of choice.

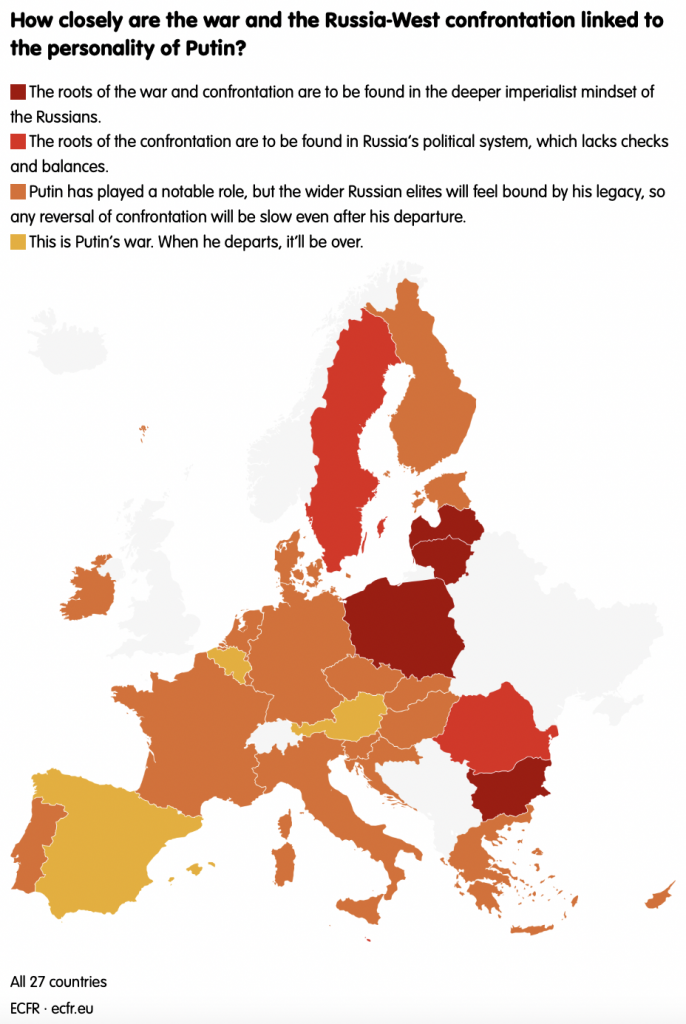

Furthermore, in 20 member states the predominant view is that the war is not just Russia’s, but Putin’s – something that springs from the Russian president’s personal idea of Russia, Ukraine, history, religion, and the world order. However, European policymakers largely believe that, even if this is Putin’s war, the members of Russia’s wider establishment will have trouble distancing themselves from it, even if they so desired. Bar a major rethink, post-Putin elites will also be bound by whatever constraints the war imposes on Russia’s future foreign policy choices.

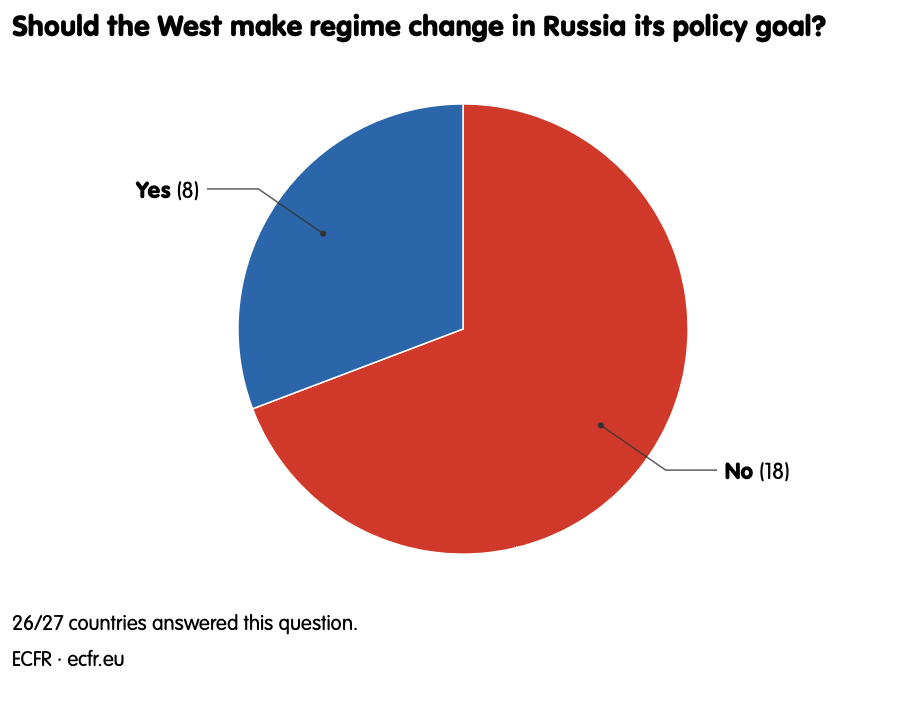

Answers to the question of whether Europeans should define regime change as a goal present a seemingly split picture. A slight majority rejecting this suggestion. Sceptics state that Europe lacks the means to bring about such a major change; and the West’s track record on regime change in the twenty-first century gives them little confidence in this sort of undertaking. However, on a closer inspection, there is more nuance among decision-makers than first appears. Policy elites in some countries may not believe that Europeans can do much to bring regime change about, such as by assisting friendly political forces within Russia, but they nevertheless judge it to be desirable. They think that Ukraine’s future military success and Western-led sanctions, in combination, could eventually create conditions for change inside Russia over the longer term. At the same time, those respondents who believe regime change to be unrealistic nonetheless also reject the idea of any sort of functional, cooperative relationship with Russia under Putin. Europeans therefore appear united around a position that could be summed up as ‘we are not going to instigate regime change – but we would not mind it happening and Russia changing.’

Questions about the EU’s future relationship with Russia elicited little: few capitals appear to be giving this any serious thought. Several respondents said it is impossible to know what kind of Russia will emerge from the war, making it impossible to plan. Decision-makers understand that, by launching the war, Putin has put the Russian system under a huge stress test, and how it will fare remains to be seen. It needs to be said, though, that the idea of Russia falling apart territorially – which is often voiced in the media – finds almost no traction among policymakers: in no country do they agree this is a policy goal or even a possibility.

Instead, European thinking focuses on the near term. Most respondents agree that in this context the most important task, in addition to supporting Ukraine, is to decouple from Russia. This is especially the case as concerns energy supplies, and to safeguard Europe from Russia militarily, economically, and in the cyber and information spheres. And, while they do not know the outlines of the future, they believe the change in relationship is likely irreversible: almost no one believes a return to ‘business as usual’ to be possible – although Hungarian decision-makers would like this, as would some in Cyprus, the opposition in Bulgaria, some parties in Italy, and fringe parties in many countries.

An important question concerns Europe’s future cooperation with Russia (assuming no regime change occurs there). The power audit enquired about the areas in which cooperation with Russia could still be possible and feasible. While pessimism reigns and the picture is bleak, climate change and nuclear arms control receive the most mentions as areas where some productive relationship might still be possible. Perhaps even more interesting, however, is the other side of the question – the areas in which European states see dialogue with Russia as undesirable from their country’s point of view, but fear that other EU capitals might still seek it. Replies here might be indicative of the limits to intra-EU trust that still exist, and that Europeans are not fully aware of how profound and wide the changes in countries’ Russia policy have been. Respondents in Romania and Lithuania, for instance, place regional conflicts in their wider neighbourhood in this category. In Spain, Italy, Malta, and Austria they point to Middle East and Africa, and some also include the Iran nuclear deal. The future geopolitical order and energy supplies also feature prominently among the answers of policymakers from a number of countries. In Germany, only China policy, and, in France, only energy supplies receive mentions. For Poland, though, all potential dialogue areas are classified as susceptible to this, while in Finland and the Netherlands no one suggests this to be a risk in any area.

Finally, the future also looks unclear for the longer-term fate of the European security order, including Ukraine’s and Russia’s places within it. Sentiments in this regard echo the thinking as concerns the global order: respondents realise that what was there has been lost, but what replaces it is not yet visible. There is a prevailing understanding that the relationship with Russia will have to change: Europe can neither return to the model it envisioned in the 1990s, nor even to the frustrating grooves that guided the relationship during the last decade or two. What awaits Europe is a transformed relationship with a transformed Russia, the actual contours of which are not yet visible through the fog of war. And, while some policymakers, such as Macron, occasionally attempt to consider the future model of the relationship, he has few followers, as the majority seems resigned to the notion that the outcome of the war will define the parameters of any future settlement. “Orders die in the wars, and are built from ashes,” as one decision-maker said.

Russians in exile

Defining a post-war policy towards Russia may be a task for the future, but European leaders should certainly aspire to craft a more workable policy towards Russians in exile – whose numbers have ballooned since the start of the war and mobilisation in Russia. Currently, few EU capitals state that they have any such policy: most say that they treat Russians as any other exiles or refugees, according to provisions of the law. Those few that have considered the issue have chosen different approaches: while Poland has never encouraged the immigration of opposition-minded Russians, Latvia and Lithuania, for instance, have actively welcomed them, at least until recently.

Russian diasporas in different EU member states differ greatly in size and nature. Latvia and Estonia have large groups of Soviet-era immigrants, many of whom quietly harbour pro-Kremlin views, or who at least are sympathetic towards official Russian positions. The power audit found that policymakers in Latvia in particular are aware that their government’s policies towards Russia are not overwhelmingly shared by a sizeable number of its Russian-speaking population.

Diasporas tend to be smaller in western Europe, consisting in most countries of Russians who have married local citizens, arrived as students, or bought property and settled. The south of France and Italy are also longstanding destinations for members of Russia’s top elites, many of whom have bought second homes there. Countries such as Cyprus, Portugal, and Malta have for some time run ‘golden visa’ schemes – arrangements whereby residency or even citizenship is made available in exchange for payments or investments. Respondents report that the war has led these states to review such schemes.

Politically active Russian emigrés have typically arrived since 2012 (with a few opposition figures having fled earlier). Many of them have settled in Latvia and Lithuania, or, less commonly, in Germany and Estonia. The survey shows that Latvia and Lithuania in particular have encouraged the activities of anti-Putin opposition, and welcomed media outlets and organisations that have wanted to set up a presence in the EU. Germany and Estonia have been more passive recipients of emigrés, while in Poland, quite notably, the Law and Justice party government has never favoured immigration from Russia, including of opposition figures, despite its anti-Kremlin stance.

Since the survey was conducted, the dilemmas, limits, and trade-offs of interaction with the exiled community have become ever clearer. In the Baltic states in particular, the prevalent instinct to be cautious about all things Russian – sharpened by the war into a purist and maximalist stance – has clashed with the desire of the Russian opposition to self-identify as Russian, as part of Russia’s political and media landscape. This led to Latvia revoking the licence of the Russian opposition television channel Rain, which had been forced to quit Russia in the summer – a move whose wisdom some figures in the EU have discreetly questioned.

The situation is further complicated by recent border closures and visa restrictions for Russians entering the EU on short-stay Schengen visas. This was initiated by the Baltic states in late summer, but from late September onward Finland, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Norway also adopted similar measures. The Baltic states introduced the move ostensibly on security grounds, although its wider impact was always more likely to be one that makes life harder for ordinary Russians. Equally, the prospect of hosting large numbers of conscription-age Russian males may in any case have appeared daunting on its own terms for border countries already looking after thousands of Ukrainian refugees. However, states’ visa policies differ, and their laws vary and are often enforced unevenly. This has made life extremely complicated for Russians already in the EU, most of whom do not want to seek asylum, but prefer to rely on long-term visas or (usually time-limited) residency permits. Until the end of the summer, this was not a problem, but since September even such EU permits do not necessarily grant assured passage for Russians through some border crossings in the Baltic states and Poland.

The role of outside powers

Another area where Europe lacks firm policy is on the question of outside powers. The survey asked policymakers to share their states’ positions on what role other countries or regions play when it comes to dealing with Russia – from the US and United Kingdom to China and the developing countries of the global south. While views about the US and the UK are firming up, thinking regarding the rest of the world ranges from the embryonic to the apathetic.

The Biden administration earns applause all round from EU states as diverse in outlook as France and Lithuania. There is consensus that the US is indispensable to European security, including, for example, among French decision-makers, who have long supported the development of Europe’s strategic autonomy. The power audit confirms that Paris is now seeking to square an autonomous Europe with maintaining a strong transatlantic relationship. Overall, Europeans view the Biden-led US as a reliable, effective, and like-minded partner. What differences there may once have been – France has considered some US statements riskily hawkish, the Baltic states have thought of the United States’ pre-war arms control approach as dangerously dovish – remain side issues in what is overall a productive relationship. Nearly across the board, however, Europeans worry about the outcome of the US presidential election in 2024.

Policymakers from the majority of member states welcome the UK’s early weapons deliveries to Ukraine. The sentiment is shared in countries as varied as Austria, Poland, Croatia, and Italy – even if some point out that former prime minister Boris Johnson’s motivation for doing so had strong domestic political, if not opportunistic, roots. The UK’s overall importance for European security is nowhere near that of the US, though. And no EU country appears to assume that cooperation in the security sphere will necessarily improve the overall UK-EU relationship: for this to happen, they state that Brexit-related issues still need to be addressed.

In contrast, views across the EU form no consensus when it comes to the question of what the war means for Europeans’ relationship with non-Western powers. Thinking about China, in particular, remains especially underdeveloped. Many policymakers surveyed accept that the EU should avoid economic dependence on authoritarian countries and agree it should work to avoid this in relation to China. But there is no clarity at all on how to view the relationship between Russia and China, or of what Russia’s war implies for Europe’s geopolitical choices. In 5 countries the prevailing view appears to be that the war means the EU should try to maintain a cordial relationship with China, to prevent it from siding more strongly with Russia. In 8 countries, policymakers resign themselves to the prospect of having to contain Russia and China simultaneously, but admit that the prospect of success in such a confrontation remains far from granted. In Malta, policymakers think that as China is a bigger and more systemic threat, the EU should aspire to normalise relations with Russia.

European policy elites are also hesitant to spell out, in the light of the war, how exactly they will pursue their relationships with countries such as Middle Eastern fossil fuel exporters given their human rights records. The majority of respondents prioritise the standoff with Russia and say that Europe should work with anyone who helps to defeat Russia. However, this realist stance does not seem deep-seated, so policies in this area could become event-driven, with preferences on partnerships reflecting the latest media coverage.

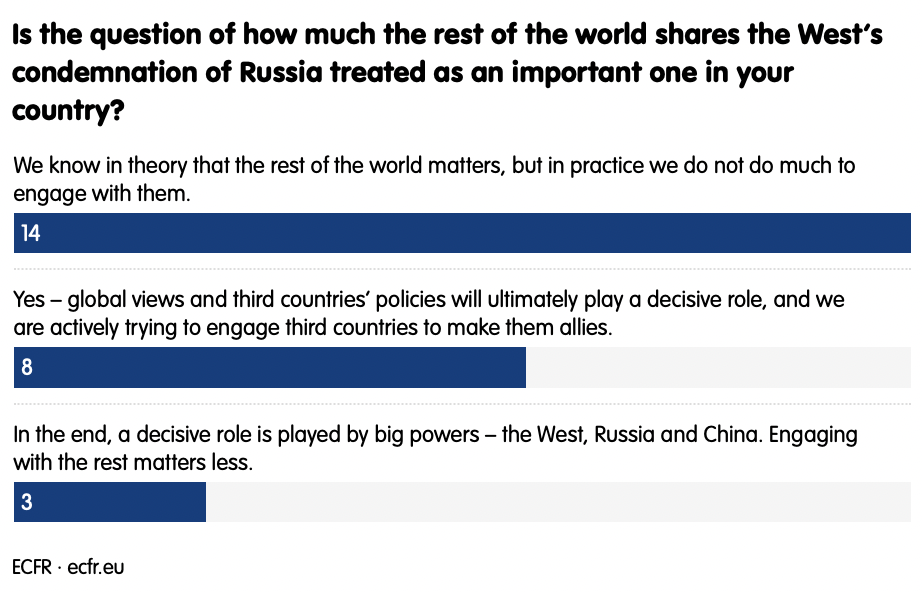

Finally, while policymakers in the EU know that they need to win over global public opinion, they admit they have had little success on this front. Indeed, most respondents report that their governments have made little effort to do so. Exceptions to this include Finland’s foreign minister, Pekka Haavisto, who has used anti-colonial rhetoric to try to win over formerly colonised countries: “We [the Nordic countries] were strongly condemning the colonial behaviour of some countries on the African continent. We are asking African countries to understand our position in this situation. When international rules are broken, countries should not stay neutral, they must open their mouths and make a stand.” But, by and large, there appears to be little energy in the EU dedicated to addressing the complex solutions needed to satisfy the global south’s food and energy needs alongside Europe’s aims of defeating Russia and tackling the climate emergency by reducing fossil fuel use.

What Europeans can do next

For Europe, Russia’s war on Ukraine truly marks the end of an era. The idea of Europe “whole, free, and at peace” – as a continent shared between Russia, the EU, and others – is distinctly out of reach. And Europe’s habit of viewing all its partnerships through the prism of rules, norms, and human rights no longer seems tenable.

The road ahead looks hard for Europeans, and policymakers’ prognoses are gloomy. However, so far governments have worked at pace to address practical matters. And they have done so with some success: lining up new sources of gas for the winter was no small feat. They can go further on this and other matters to shore up their position and provide themselves with space to contemplate the longer-term challenges posed by their relationship with Russia.

Win over public opinion before it turns

European politicians should not shy away from communicating to their domestic audiences what is at stake, including setting out how long countries could face continued inflation and energy shortages. Such honest communication would help set expectations and thereby head off potential complaints about European societies being pulled into a drawn-out engagement without their approval. As ECFR’s earlier research has shown, European publics are overwhelmingly supportive of Ukraine. They will be receptive to such messaging and appreciate honesty, even if the message is harsh.

Work towards an EU-wide energy policy

So far, securing new energy supplies has taken the form of muddling through, with many states adopting ad hoc and country-specific solutions. A recommendation for the coming period should be to move towards a more coherent, EU-wide approach – one that takes account of supply security issues, and one that different member states, with their different economic profiles, agree is fair. If they devise this well, Europeans could successfully target a range of political goals: from resisting Russia, to maintaining environmental and climate standards, to reaching out to the global south. Looked at this way, a successful decoupling could prove a win-win-win for Europeans and their wider-ranging political agenda.

Design strategic sanctions

The EU should aim to break the cycle of responding to each new Russian atrocity with the imposition of ever more sanctions. This approach is media-driven, hard to maintain, and ultimately unproductive. The emphases should shift from ad hoc and personal sanctions towards a more structural and strategic approach with the aim of undermining Russia’s capacity to wage war in the short term as well as the long term. Lately the EU has been moving in that direction; it should continue with this approach.

Devise an approach towards anti-regime Russians

The EU should think of a policy that accounts for anti-regime Russians who have left the country. This will be hard – as much of what can be done to help (or hinder) them remains the prerogative of member states; but the EU could put forward some basic principles or examples of good practice. The EU has always been keen to reach out to civil society in Russia; and, for now, the exiled Russians – who are active on social media and often in touch with friends and relatives in Russia – are the EU’s best link to Russian society. There will doubtless be limits to this relationship: Russian exiles’ aims and views may not perfectly overlap with those of many in the EU. Political activity in exile can at times be toxic and embittered, and there is no guarantee the current emigrés will play a prominent role in a post-Putin Russia. Even so, the benefits of engagement seem to outweigh those of non-engagement. And, as concerns practical arrangements and bureaucracy – it would simply be humane and in keeping with EU principles to try to reduce the currently Kafkaesque red tape faced by many exiles – even if they come from an aggressor state and lack official refugee status.

Articulate a vision for the EU’s future relationship with Russia

Finally, the EU should seek to articulate a vision for its future relationship with Russia, even if it remains only embryonic for now. While almost everything about the future relationship will depend heavily on the outcome of the war and what kind of Russia emerges from it, the EU could still make clear that it expects there to be a future Russia. This would counter the Kremlin’s argument that the war is existential, that if Russia loses it there will be no Russia. Worryingly, this line has often recently been adopted by some in Russia’s expert class who shape elite opinion. It might help if the EU – or other key Western institutions or leaders – set that out. While the Putin regime might have made the war an existential issue for itself, this need not be the case for his country. Russia will remain, even if Putin does not survive his war.

Conclusion

The EU and its member states are experiencing tough times, and their leaders are right to worry about the future. But a newly creative EU is emerging from the gloom. Decision-makers throughout the bloc have recognised the definitive end of the world they knew – they mourn its loss, but the war has also freed them to think differently. In their relations with Russia they are no longer bound by the normative framework that, for years preceding February 2022, they could neither abandon, nor make work.

The change that Russia has provoked may also help the EU and its member states prepare for life in a world where the West’s relative role is smaller than it was. In this regard, Putin might be careful what he wishes for: the West might indeed lose its hegemon status, as he has predicted. This shift will have little to do with Russia, which has failed live up to the threat many feared. But Putin and his war may nevertheless have forced Europeans to face the new reality head on, master a new agility that helps them and their allies through this crisis, and better adapt to the times to come.

Methodology

ECFR-affiliated researchers in the 27 EU member states responded to the Russia power audit questionnaire on the basis of interviews they conducted with decision-makers and members of the wider political class in their country. This means that the outcome is neither a public opinion survey nor a collection of official positions and talking points. Instead, the aspiration is to acquire an understanding of the political class across the EU 27 that tries to probe deeper undercurrents of thinking: considerations affecting different countries’ decision-making and the constraints in which the individual countries operate.

About the author: Kadri Liik is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Her research focuses on Russia, eastern Europe, and the Baltic region.

Acknowledgments

I want to send my heartfelt thanks to ECFR’s network of national researchers: Isabella Antinozzi, Adam Balcer, Vladimir Bartovic, Robin-Ivan Capar, Euan Carss, Lívia Franco, Vincent Gabriel, Harry Higgins, Jule Könneke, Marin Lessenski, Tara Lipovina, Marko Lovec, Daniel Mainwaring, Justinas Mickus, Matej Navrátil, Christine Nissen, Aleksandra Palkova, Ylva Petterson, Oana Popescu-Zamfir, Astrid Portero, Martin Quencez, Mathilda Salo, Sofia-Maria Satanakis, Hüseyin Silman, George Tzogopoulos, Niels van Willigen, Viljar Veebel, and Zsuzsanna Végh. The data you submitted has been invaluable: it has provided me with granular understanding of thinking in the different EU member states; it has shown that there is actually more unity in the EU than the EU itself may realise; and, while only a fraction of this knowledge made its way into print, the publication would not have possible with it.

Extensive EU-wide research also costs money: this publication has been supported by the German Federal Foreign Office and Sweden’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, cooperating with whom has been a pleasure on intellectual, professional, and personal levels. I also want to thank my ECFR colleagues: Susi Dennison and Rafael Loss helped to design the research in the 27 member states; Adam Harrison has been a most thoughtful editor; Marlene Riedel designed the graphics; and Marie Dumoulin, Tefta Kelmendi, and Gabriele Valodskaite have been supportive colleagues in the Wider Europe programme.

Finally, and given that ECFR has just turned 15, it feels proper to acknowledge all of ECFR and Mark Leonard for creating an environment where pan-European relationships can be discussed in intellectually sharp, curious, honest, but empathetic and respectful manner. It remains completely unclear how this has been achieved, but it is quite clear that this benefits Europe.

Source: This article was published by ECFR