Ebola In DRC: Violence And Instability In A Hot Zone – OpEd

By Paolo Zucconi

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) could be one of the richest countries in the world, but its recent history only consists of internal conflict and poverty. Governed by the Kabila dynasty from 1997-2018 and affected by decades of civil wars and humanitarian crisis, the country is a huge source of rare minerals and raw materials. Coltan, for example, is a key material used in various high-tech industries, including aerospace. Extracted by thousands of slaves, the mineral has been illegally extracted and sold via Burundi since 1995. Over the years, many armed groups emerged to seize control of the mines, employing large-scale violence to make profits from the illicit trade.

About 13 million people today depend on foreign aid in Congo. About 4.1 million are refugees – more than in Syria. The new president, Felix Tshisekedi, won in disputed elections last year and has called for national reconciliation.

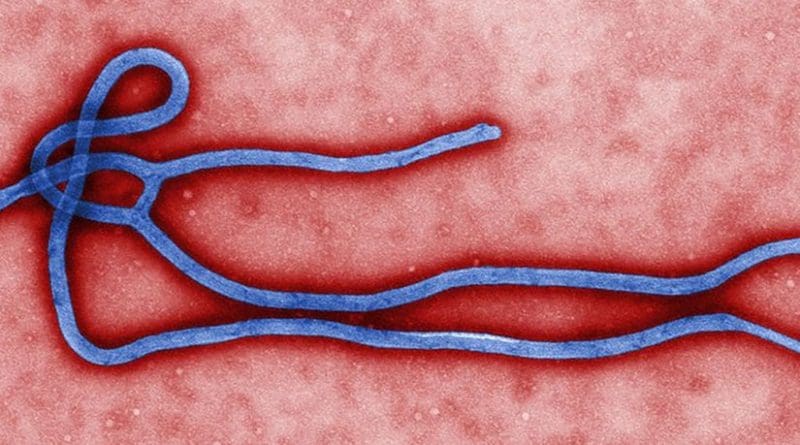

Whereas eastern Congo is no longer affected by heavy military clashes with its neighbors, in the last two years, smaller scale cross-border dynamics have intensified and armed resistance increased. There are about 100 militias fighting government forces. However, civil wars and internal conflict is not the only problem. The latest Ebola crisis is also spreading, and the worst-hit areas are already heavily affected by violence and poverty.

According to Doctors Without Borders, the Ebola epidemic in Congo is out of control. About 570 people have died so far and another 907 are infected. The current crisis is considered the second worst in the history of Congo and it is spreading fast for several reasons:

First of all, widespread instability and armed conflict is impacting the epidemic response, with health workers recently being attacked at two Ebola treatment centers in Katwa and Butembo. There are high risks for personnel working in the hot zone, who risk being kidnapped or killed. Doctors Without Borders had to suspend its activity in those areas because of a critical situation. New medicines and experimental vaccines continue to arrive, but distribution is extremely difficult. Katwa, near the Uganda-border, is the most critical area. Several cases are also in Butembo and the outbreak could spread into other villages and cities, where there are not any properly equipped medical facilities nor trained personnel for containment, and where there are more migration flows to Rwanda, South Sudan, Uganda.

Long-term tensions and clashes between the government and rebel groups aren’t helping in the fight to contain the Ebola outbreak. The Kivu conflict is one example. Between 2004 and 2008, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) and the Hutu group Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) fought over control of rare minerals and natural resources in the region. There are still clashes ongoing, which impedes effective anti-Ebola strategies from being implemented.

However, this is not the only problem. According to Joanne Liu, President of Doctors Without Borders, local police coerce people to go to Ebola treatment centers to comply with health measures against Ebola. But this is leading to further alienation among the community, and is counterproductive to controlling the epidemic. Not all the people who are being forced to move are infected. There is a communication issue. Due to coercive measures, locals do not perceive these centers as a solution, choosing instead to hide in their own communities. As a result, over 40% of fatal cases pass away in the community and not at a health clinic.

The increasing militarization of this crisis risks negative effects, especially with regards to trust – an important commodity given the DRC’s sectarian conflicts. The key challenge concerns community mistrust, especially in Katwa. Community members are not proactive in reporting suspected cases and refuse to cooperate with operators in the treatment centers. A major role should be played by the government in strengthening community-based prevention policies. Local police is necessary to endorse cooperation between foreign operators and the local population, as well as to provide a local security presence to reassure locals. However, local police should not exercise discretionary power on reporting suspected cases and/or act as coercive authority. Otherwise, there’s a risk of alienating the people whose cooperation is crucial in containing the outbreak.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the authors are associated.