China As COVID-19 Scapegoat – OpEd

After the disastrous mishandling of its COVID-19 battle, the Trump White House blames China for the virus, at the cost of American lives and worst contraction since the 1930s.

Ironically, President Trump thanked President Xi for China’s success in the virus battle in late January. But he adopted a very different tone as the White House mishandled the outbreak permitting the virus to spread in America [for the full story, see my COVID-19 report, The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities].

In fact, Trump’s own cabinet took an adversarial stance from the beginning. If the escalation will continue, that stance could result in a new Cold War and the Second Global Depression in the coming years.

Blaming China for Trump’s COVID-19 mishandling

The efforts to exploit the crisis for political purposes began early in the year. On January 30, right after the ‘Phase 1’ trade deal and the national virus emergency in China, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross declared the outbreak in China would benefit US manufacturing and bring jobs back to America. He was seconded by Trump’s trade advisor, Peter Navarro, who pledged US tariffs on Chinese imports would not be lifted even if the deadly coronavirus weighs on China’s economy.

Despite the first novel coronavirus cases in the US, both Ross and Navarro apparently presumed the virus would not spread in America.

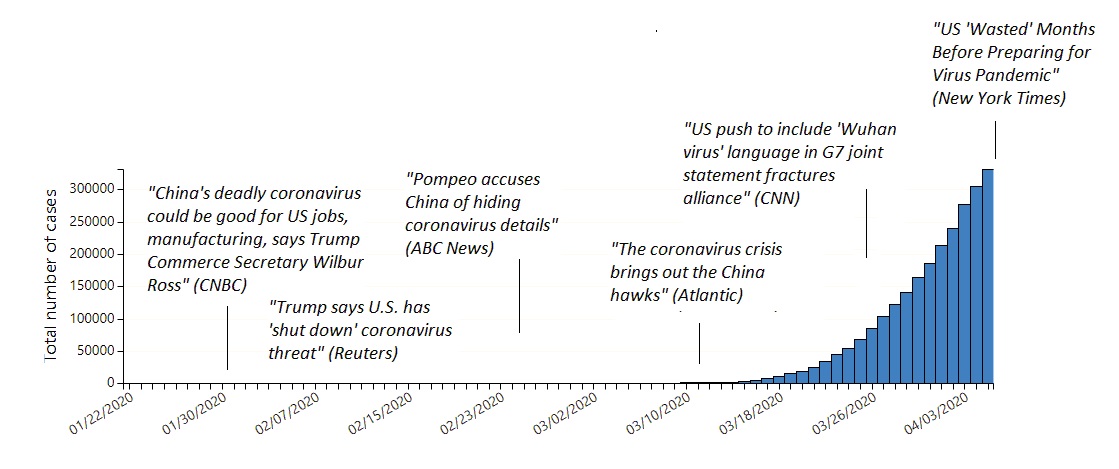

Between early January and mid-March, the Trump White House’s accusations against China intensified with broad criticism of the administration’s mishandling of the outbreak, particularly as US debate escalated over botched evacuations, faulty test kits and delays in testing, shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) and additional PPE shortages due to tariff wars, failed responses and associated elevated health risks, inadequate quarantines, failed self-quarantines, premature exits from lockdowns and the list goes on.

That’s when politicized attacks were initiated by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar who blamed China for the U.S. virus crisis. Meanwhile, Trump sought to “talk down” the virus impact in the markets.

When the WHO declared the global emergency on Jan 30, Trump still claimed that “we have it very well under control.” Even in early March, he described the virus as “very mild” and said the infected could get better by “going to work.”

Ironically, as the Trump White House repeatedly labelled the virus a “China virus” or “Wuhan virus,” that fostered a perception that the outbreak would be limited to China, while it was actually exploding in America and Europe.

When these deflection efforts failed to halt public criticism of the administration, the Trump White House began to exploit even reputable media to launder unsubstantiated intelligence meant to ratchet up tensions with China. The hope is that scapegoating – the “Chinagate” – would steer attention away from the Trump administration’s catastrophic disastrous mishandling of the COVID-19 crisis.

That’s why the politicized efforts to re-redefine the COVID-19 as the “China virus” continued into late March (and prevail even today). That’s when the numbers of US virus cases and deaths began to soar.

Use of scapegoats in paranoid politics

Instead of international cooperation to beat the pandemic, the Trump White House and its Republican supporters are on a survival mode. They hope to ensure Trump’s second term. That’s why another critical moment was missed when Pompeo called for COVID-19 to be identified as the “Wuhan virus” at the G7 Summit in late March.

Obviously, European officials resisted the redefinition since the WHO had cautioned against giving the virus a geographic name because of its global nature. But in the process, precious time was missed as US domestic political priorities overrode the urgency for international cooperation against the global pandemic (Figure).

The purposeful use of projective bashing of targeted scapegoats has a long history in US politics. In the mid-1960s, Richard Hofstadter, the iconic historian of postwar liberal consensus, defined it as a recurring “paranoid style in American politics.”

In the effort to explain away the presence of class, ethnic, and immigration divisions in America, this style projects such divides onto other countries, real or imaginary adversaries, as evidenced by the 1950s McCarthyism, the Trump administration’s controversial ties with the U.S. alt-right movement, and Trump’s personal paranoid style that sparked warnings by leading American psychiatrists and psychologists already three years ago (The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump, 2017).

These views have been echoed by former US ambassador to China Max Baucus, who recently warned that he feared the Trump administration’s rhetoric against China was leading the US into an era “which is similar to Joe McCarthy back when he was red-baiting the State Department, attacking communism.”

Months of missed opportunities

The Trump administration knew about the virus risks already by January 3, when CDC Director Dr. Robert R. Redfield called Secretary of Health Azar, telling him China had discovered a new coronavirus. Azar made sure the National Security Council (NSC) knew about the virus because in early 2017 Trump had eliminated NSC’s global health unit, despite warnings about possible future pandemics.

As the New York Times has reported, the new virus team began daily meetings in the basement of the West Wing, yet no mobilization was initiated. Rather, a long debate began within the White House over “what to tell to the American public,” even as Trump, Pompeo and Azar blamed China for the lack of transparency.

Although the government’s leading scientists and health experts raised the alarm early and pushed for aggressive action, they faced resistance at the White House. Trump didn’t want markets to be spooked by panic. As a result, misguided political priorities continue to override science-based policies stressing public health.

The cult of secrecy in the White House has not eased. In mid-April, Dr Anthony Fauci, a key member of the virus task force, was asked by the CNN, whether earlier mitigation efforts could have saved more lives. Truthfully, he admitted: “If we had right from the very beginning shut everything down, it may have been a little bit different. But there was a lot of pushback about shutting things down back then.” Hours later, Trump retweeted a user who said it was “Time to #FireFauci.”

The recent confrontation between Trump and Fauci about the dangers of a premature exit from the lockdown is still another example of Trump’s political priorities, at the expense of American lives and U.S. economy.

Whatever the ultimate reason for the painfully long delay in the mobilization against the virus in America, the fact remains that, like Hong Kong and Singapore after January 3, the Trump White House could have begun the virus battle proactively.

For almost three months, it chose not to. And when it could no longer could hide its catastrophic mistake, the White House blamed China for the catastrophe.

The commentary is based on Dr Steinbock’s briefing on May 16 and report, The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities, see https://www.differencegroup.net/coronavirus-briefs