Examining The West’s Misguided Approach To The Horn Of Africa – OpEd

Last week, a 61-page human rights report about Ethiopia was released, detailing the government’s heavy-handed response to large and widespread anti-government protests and dissent over political and economic inclusion. According to the report, Such a Brutal Crackdown: Killings and Arrests in Response to Ethiopia’s Oromo Protests, during the widespread protests, largely arising within the Oromia region, Ethiopian security forces have resorted to excessive and unnecessary lethal force and mass arrests, engaged in the harsh, ruthless mistreatment of those in detention, and restricted access to information. Estimates suggest that over 400 protesters or others have been killed by security forces, while tens of thousands more have been arrested.

Notably, just days prior to the release of the report, Ethiopia launched an unprovoked attack on Eritrea, its northern neighbor and former colonial possession. The attack occurred on Eritrea’s Tsorona Central Front, located along the tense, militarized border between the two countries and which was the scene of some of the fiercest fighting during the 1998-2000 Eritrea-Ethiopia war. Late in the evening on the day of the attack, Eritrea immediately reported the incident and then quickly called upon the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to take appropriate action while, in contrast, the Ethiopian government offered several different, extremely puzzling, and highly contradictory accounts of the incident without adequately justifying its attack.

Although the events encapsulate Ethiopia’s utter contempt for international laws, flagrant disregard for basic human rights, and the overwhelming “politics of fear” that pervades the country’s socio-political landscape, they also reveal in crystal clear detail the highly troubling role of much of the international community, led by the US, within the region. For example, although Ethiopia’s brutal crackdown warrants a strong rebuke and condemnation, there has been a severely muted international response, with many of Ethiopia’s foreign supporters remaining silent.

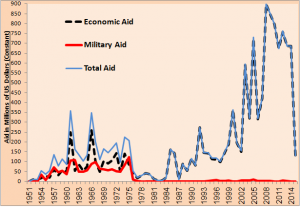

Problematically, since World War 2, the US, with the West in tow, has maintained a close alliance with a series of autocratic Ethiopian leaders, providing them with considerable economic, diplomatic, and military support and permitting them to act with impunity. Annually, Ethiopia receives hundreds of millions of dollars in aid from a variety of bilateral and multilateral sources. Across the 2004-2013 period, the country was the world’s 4th largest recipient of foreign assistance, receiving nearly US$6 billion, while in 2011 alone, its share of total global official development assistance – approximately 4 percent – placed it behind only Afghanistan. Exploring the records of successive Ethiopian leaders makes for distressing reading.1

Haile Selassie, who remained in power until the 1970s, was a despotic tyrant who ruled oppressively, enslaved innumerable peasants via a draconian feudal system, and illegally annexed Eritrea. Decades later, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, a “darling” of the West, would rule Ethiopia for 20 years with dictatorial ruthlessness. In 2005, following rigged national elections, Zenawi’s regime “massacred” hundreds of protestors, many of them youths. His tenure was also marked by the brutal crackdown on civil society organizations and journalists, the illegal invasion and occupation of several neighbouring countries (i.e. Somalia and Eritrea), the exclusion and marginalization of a number of Ethiopia’s major ethnolinguistic and religious groups from political and economic life, the utilization of international humanitarian and food aid as a “political weapon” (by restricting aid from “disloyal” segments of the population), and a violent counterinsurgency involving “war crimes and crimes against humanity.”

Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, who came to power following Zenawi’s abrupt death, is the current leader of a ruling party that won elections last year with a final tally of 100%. Under his rule, Ethiopia has continued to crush all dissent via controversial anti-terrorism laws, sustained the marginalization and persecution of various ethnolinguistic groups and homosexuals, retained the much criticized villagization programs, and sustained the heavy-handed response to anti-government protests by resorting to brutal suppression and harsh crackdowns characterized by a spate of rights violations and condemned by an array of international human rights organizations. In 2015, leaked emails revealed that Desalegn’s regime, which is now making appeals for greater aid and external support, was paying the Italian surveillance firm, Hacking Team, to illegally monitor and silence journalists critical of the government.

Even Colonel Mengistu Hailemariam, who overthrew Selassie in the 1970s, was a close ally of the USSR, and oversaw a reign of terror characterized by widespread violations of international humanitarian law and war crimes, received not insignificant amounts of aid from the West.

Beyond the propping up of tyrannical leaders that have subjected their populations to widespread, systematic, pervasive human rights violations, the US and West’s longstanding infatuation with Ethiopian autocrats is extremely problematic because it has encouraged Ethiopia’s bellicosity and aggression towards its neighbours.

In 2000, after nearly two years of brutal war between their countries, President Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea and Prime Minister Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia signed the Algiers Agreement. Subsequently, in 2001, the Eritrea Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC), composed of five prominent and highly respected lawyers was established to make its “final and binding delimitation and demarcation decisions.” The Commission presented its “final and binding delimitation decision” on 13 April 2002, with the flashpoint of the 1998-2000 war, the small, rural border town of Badme, being awarded to Eritrea.

While the decision has been accepted by Eritrea, and although the entire process was guaranteed by the UN and the OAU/AU and witnessed by the US, EU, Algeria, and Nigeria, Ethiopia has completely failed to shoulder its legal obligations and responsibility for demarcating the border. Instead of implementing the “final and binding” internationally recognized decision, Ethiopia has resorted to making regular incursions into and frequent attacks against Eritrea. Furthermore, it has persistently called for the forceful overthrow of the Eritrea government and, through belligerent, threatening statements via government-owned media outlets, proclaimed its intentions to carry out “military action to oust the regime in Eritrea.” Just this year, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, said Ethiopia was ready to take “proportionate military action against Eritrea” for Eritrea’s alleged “continuous acts of provocation and destabilisation of Ethiopia.”

In addition to its aggression toward Eritrea, Ethiopia has engaged in frequent military incursions into other neighboring countries, including Kenya and South Sudan, while it has maintained a long, violent military presence in Somalia. The illegal 2006 invasion of Somalia, subsequent brutal occupation, and ongoing involvement within the country have been widely agreed by analysts as increasing and spreading terrorism and instability throughout the region. Recently, dozens of Ethiopian soldiers were involved in a bloody battle with Somali militants at an African Union base in central Somalia, while just days ago Al-Shabaab reportedly killed a number of Kenyan policemen.

However, rather than censure Ethiopia’s illegal military occupation and repeated aggressive actions towards Eritrea or other neighbors, or call for the immediate, unconditional implementation of the EEBC decision, the US and the international community have turned a blind eye, abdicated their responsibility, and instead been acquiescent to Ethiopia’s persistent violations and hostile behavior. Notably, Eritrea accuses the US of playing a role in the deployment of weapons during the recent Ethiopian attack, and a number of Wikileaks cables reveal how successive US administrations have sought to keep the “[Eritrean-Ethiopian] border dispute frozen,” if not reverse or “reopen the 2002 EEBC decision.” Paradoxically, Eritrea has been hit by international sanctions – arising from US and Ethiopian pressure – that are increasingly recognized as illegitimate, unfounded, and counterproductive, while the tepid responses by the US State Department and UN Secretary General to the recent attacks – meekly calling for “restraint” from both sides – are resounding in their failure to condemn Ethiopia’s belligerence and effectively assign equal blame to both victim and aggressor.

When the French statesman, Talleyrand, was told by an aide of the murder of a political opponent, the aide said, “It’s a terrible crime, Sir.” In response, Talleyrand answered, “It’s worse than a crime, it’s a blunder.” Likewise is the US and West’s approach toward the Horn of Africa. Unwavering support for and appeasement of Ethiopia are part of a policy approach based upon the misguided belief, dating back to the immediate post-World War 2 period but rearticulated more recently in terms of regional “anchor states” designations, that Ethiopia is vital to protecting US and Western geostrategic interests and foreign policy aims. However, not only is this approach morally vacuous, with the US and international community being directly complicit in the mass crimes, transgressions, and reign of terror perpetrated by the Ethiopian government, the misguided policy approach has largely failed to achieve its objectives, to even a minor degree, and instead only served to stunt regional development and destabilize the entire Horn of Africa through contributing to unnecessary rivalry, conflict, and insecurity.

The people of the Horn of Africa deserve far, far better.

Notes:

1 This association between aid and human rights violations mirrors post-World War 2 trends between human rights and US foreign policy in Latin America. In a pioneering work, Schoultz investigated the relation between US aid and the human rights climate, finding that there is a strong correlation, with US aid flowing “disproportionately to Latin American governments which torture their citizens,” and to Latin America’s “egregious violators of fundamental human rights.” Importantly, Schoultz also illustrates how the correlation cannot be attributed to a correlation between aid and need (Chomsky 1985: 158; Schoultz 1981).