Britain’s ‘Print And Steam Initiative’ In The Middle East: The 19th Century BRI? – Analysis

Due to its strategic location between Europe and the Indian Ocean, the Middle East has been one of the focal points of China’s international infrastructure strategy – the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, as Islam is central to the culture and identity of most Middle Eastern societies, China faces the challenge of considering the religious implications of the BRI.

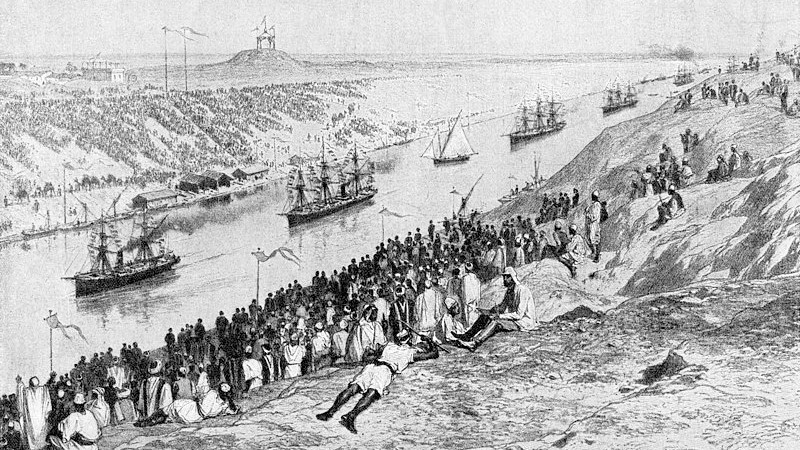

This attention to the Muslim societies in the broader Middle East was also essential for the European colonial empires, for whom connecting Europe with the coasts along the Indian and the Pacific Oceans was one of the greatest concerns of the great powers, especially in the long 19th century when colonialism was at its peak. This concern was especially acute for the greatest superpower at that time – the British Empire. Similar to China’s current BRI project, the British Empire in the 19th century also sought to increase connectivity with its colonies in the Indian subcontinent through infrastructure construction in an characterized by technologies of steam and print. For instance, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 drastically increased the connectivity between Europe and the Indian Ocean.

Two lectures for the research project “Infrastructures of Faith: Religious Mobilities on the Belt and Road” (BRINFAITH) at the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences showed how both Britain and China have factored Islam into their infrastructural outreach to the Middle East. Firstly, Prof. Cemil Aydin, Professor of International/Global History at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, suggested how the British Empire constructed a connectivity network in the Indian Ocean and the Middle East between the mid-19th and the mid-20th centuries and how Islamic religion facilitated Britain’s rule in this region.

Secondly, Dr. Kyle Haddad-Fonda, a research fellow at the Foreign Policy Association, gave a lecture on China’s efforts to incorporate Islamic religious elements into its relations with the Middle East. He investigates the case of Yinchuan – the capital of China’s Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region – as a center of Islamic and Hui Muslim culture in China for its outreach to the Middle East, and how these attempts experienced rapid change after 2018 when the Chinese government started its policy of Sinicizing of Muslim cultures in this region.

Taken together, the two lectures show how Britain’s infrastructure development from the Middle East to the Indian Ocean coasts in the 19th century resembles China’s ongoing BRI project, and how the religious aspect of these inter-state relations played a significant role for both great powers. It can also indicate how the religious factor can play a significant role for the future of the BRI through the lessons from Britain’s regional development from Arabia to Southeast Asia in the 19th century.

Britain’s ‘Print and Steam Initiative’

The late 19th and early 20th centuries are known to be the era of colonialism, when the great European powers extended their rule overseas and ruled colonies around the world. The most notable of these European powers was the British Empire, which, to its maximum extent, ruled over 24% of the Earth’s total land area and 23% of the world’s population, becoming the largest empire that had ever existed in the human history.

Britain’s influence was especially pronounced in the Muslim World. Half of the world’s Muslim population was under British control, making it the largest Muslim state in the world at that time. The region along the Indian Ocean from Egypt to the Bay of Bengal was under British rule and hosted most of the world’s Muslim population.

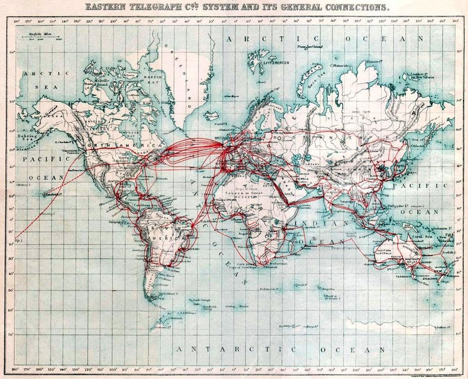

Due to its geographical significance between Europe and East Asia, it was essential to construct transport and communication networks that connected the Eurasian continent through the Middle East. Thus, during its rule in the Middle East, Britain constructed various infrastructures, such as steamship lines, railroads, telegraph lines and cheap printing, that connected not only the people and trade across the Eurasian continent but also facilitated the connectivity of the Muslims in the region.

“1857 to 1900 is when British Empire built the infrastructure of the steamship, which made travel within and between Asia and Europe much faster and safer,” said Dr. Aydin, “which then increased Muslim connectivity and travel between different parts of Eurasia and Arabia. The number of Muslim pilgrims to Mecca increased by ten times in this period.”

The Suez Canal is an example of one of these infrastructure projects financed by the British and French empires. After its opening in 1869, the travel time between Europe and the Indian Ocean was decreased from two months to only two weeks. The Canal also allowed better connectivity of steamship routes across the regions and served as the crossroad of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Moreover, the telegraph network was also constructed to communicate news and enabled information to travel much faster.

The increasing connectivity across the Middle East through Britain’s ‘Print and Steam Initiative’ caused the rise of Muslim mobility for religious activities, especially the pilgrimage.

“Steamships, run by British companies, were carrying pilgrims quickly and safely from India to Mecca, which was then creating a boom of religious excitement,” said Dr. Aydin, “because suddenly the number of pilgrims to Mecca increased from several thousand to 50-70 thousand.”

This mobility of these pilgrimages gave Britain an opportunity to appease the Muslim population within its Empire. The imperial authorities encouraged the Muslims to carry out their religious obligations – indicating how the secular British government could be favorable towards the Islamic religion. The British Empire also made efforts to incorporate Muslims’ religious faith to ease its rule over its colonies, such as when Queen Victoria announced the Proclamation of Religious Freedom in India in 1858.

These pro-Muslim policies led to a symbiotic relationship between the secular British administration and the religious identities of Muslim population. Because Britain, at that time, was the country with the largest Muslim population, it needed to incorporate Islamic religious faith into its colonial rule. For example, Wilfred Blunt, an anti-imperialist English writer, claimed that Britain was in a unique position after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, as it would increase Muslims’ reliance on British rule as their custodian and protector. As a result, Britain could use the Islamic world as a tool to increase its global hegemony.

Indeed, Muslim revolts against British rule were rare from 1857 to 1914. The Muslim population’s loyalty towards the British Empire was also visible in World War I. Around 400,000 Muslim soldiers were recruited during the war, which legitimized British rule over the Islamic population. Even when the Ottoman Empire declared war on Britain and tried to use Islamic identity to undermine Muslims’ loyalty towards the British Empire, Muslim soldiers and populations remained loyal to British rule.

“There was an awareness that the British provided the infrastructure,” said Dr. Aydin, “and Muslims could work to gain rights within the British Empire.”

At the same time, however, the British colonial officers were also anxious that the increased connectivity of the Muslim populations might also result in a single Muslim identity that could revolt against the British rule. What if the increased mobility and number of Muslim pilgrims resulted in their unity against colonial rule and European racism towards Muslims?

“So, the British become paranoid – on the one hand, they are encouraging Muslims to connect and providing the infrastructure,” said Dr. Aydin, “on the other hand, they also become worried that if all these Muslims bond together in solidarity, they may end their rule.”

According to Dr. Aydin, Islamophobia among the British rulers ultimately became the main factor that disrupted the legitimacy of the British Empire. For instance, British Prime Minister William Gladstone first came up with the policy of ‘liberal Islamophobia,’ which justified Christians’ rule over Muslims in India, while depicting Muslim rule over Christians in Ottoman Greece and Bulgaria as unjust, vile and despotic.

Even though the Muslims showed loyalty towards the British Empire, the racialization and marginalization of the Muslim population from British Christian rulers gradually undermined the legitimacy of the British Empire’s rule over the Middle East. Eventually, Britain’s legitimacy was lost after World War I, when the Balfour Declaration in 1917, which promised to create a Jewish homeland in Muslim-majority Palestine, was considered by Muslims to be a violation of Britain’s promise to the Indian Muslim soldiers sacrificing their lives for the empire .

As the 19th century British experience in the Middle East indicates, infrastructure projects in the region enabled British Empire’s rule over the Muslim population, as it incorporated and tolerated the Islamic religion in its governance, transforming Britain into not only the world’s largest empire but also the world’s largest Muslim Empire. The ‘Print and Steam Initiative,’ therefore, was a win-win situation that mobilized Britain’s colonial rule in the Middle East while also promoting and securing Muslim connectivity and religious activities through their loyalty towards the Empire. The racialization and Islamophobia among the British rulers, however, disrupted this symbiotic relationship and destroyed Britain’s legitimacy.

China’s Outreach to the Middle East: Déjà vu?

China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ seems to resemble Britain’s earlier ‘Print and Steam Initiative’. Both target the Islamic Middle East as a region that connects Europe with the Indian Ocean and East Asia and promote constructing transport and communication infrastructure networks that can vastly increase regional connectivity. As a region where the Islamic identity is central to most societies, it is essential for China to consider the religious aspects of the Middle East, as the British Empire attempted in the 19th century.

Has China made efforts to embrace Islamic religion in its infrastructure project? Dr. Kyle Haddad-Fonda’s lecture suggested mixed results. While Beijing attempted to use Islam as a primary factor to draw Middle Eastern countries’ attention to China, these approaches fizzled out after China promoted the Sinicization of the domestic Muslim populations since 2018.

The tensions around the Sinicization movement are visible in the city of Yinchuan – the capital of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region – where about 25% of the population is known to be the Chinese Muslims, known as the Hui ethnic minority. Due to its relatively high ratio of Chinese Muslims, Yinchuan was promoted in the Middle East as a ‘cultural tourist destination’ before 2018.

The narratives on the Hui people also attempted to associate how the Middle East has a long historical relationship with China, describing the Hui as the descendants of Arabian and Persian merchants who came to China for trade. Even though the Hui do not fit the Chinese ethnic minority policy – they do not have a single region of residence and a common language distinct from that of the Han Chinese, that is, Mandarin Chinese – they were designated as an ethnic minority with an inherent affinity to the Middle East and the Arabic language with an idea of common descent.

“My sense is that over time, people in China and the Chinese government itself have been very inconsistent about the extent to which they are comfortable recognizing Arabic as something that Hui Muslims are supposed to feel an affinity for,” said Dr. Haddad-Fonda, “so sometimes, particularly in the 2010s before 2018, you see people emphasizing that it is important for Hui Muslim to know Arabic, but then other times after 2018, you see articles saying ‘no, no, no, the common language of Hui Muslims is Mandarin.’”

Hence, before 2018, Beijing utilized Hui Muslims as a bridge to connect China with the Middle East, which led to a transformation of Yinchuan city into a place full of Islamic and Arabian characteristics that could draw Muslim countries’ positive attention to China. For instance, street signs were written in Arabic along with Chinese and English; an ‘Islamic’ theme park was built with buildings that resembled mosques in Middle Eastern styles; Arabic was also taught in schools.

The Hui Culture Park in Yinchuan was notably built to propagate Hui Muslim culture to tourists. Local Hui Muslims, who spoke Arabic, were employed in this park to work as guides for foreign visitors. The buildings in the park were built in an Arabian architectural style with golden domes, minarets, and Islamic designs that give the visitors impressions and experiences of Islamic culture in China.

These strategies were a form of cultural diplomacy that appeals to the Middle Eastern countries, using the Islamic religion to promote favorable China-Middle East relations. Due to its rapid rise and the necessity of a close relationship with the Middle East for the success of the BRI, the authorities in Ningxia emphasized Hui Muslim culture for its outreach to the Middle East.

“In the 2010s, as the Chinese government was eager to present Hui as more assimilated and palatable as Chinese Islam could be, Ningxia, where Yinchuan is, became the place to go for the foreign visitors,” said Dr. Haddad-Fonda, “Yinchuan was promoting itself as a China’s gateway to the Arab world.”

Presenting Yinchuan as a ‘Muslim city in China’ not only attracted investments from Middle Eastern countries for the development of the city itself, but also gave the Hui Muslims a special role in China’s policy to construct the ‘21st century silk road’ and its outreach to the Middle East. In fact, the accommodation of religiosity in China’s domestic development led to Muslim countries’ favorable approach to China and facilitated China’s outreach to the Middle East. For instance, Emirate Airlines inaugurated a new direct route from Dubai to Yinchuan in May 2016 – its fourth direct flight to Mainland China after Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.

“If you look at the publications by Arab visitors to Yinchuan, they praise the Chinese government’s support for Islam in China and the enthusiasm about how many people in Yinchuan were learning Arabic,” said Dr. Haddad-Fonda, “this was the message that was getting out in the 2010s.”

Official efforts to present Yinchuan as the representative of Islam in China for its outreach to the Middle East, nevertheless, experienced rapid changes after 2018, when Beijing’s concerns about Islam led to tighter constraints on religious matters across the country. Not only in Xinjiang, which has a large Muslim Uyghur population and secessionist movement, but also every Muslim ethnic minority’s’ association with the Islamic religion was targeted for transformation to become ‘Chinese-oriented.’

These restraints became visible in Yinchuan, especially in the policy about the Arabic language. Signs and displays in Arabic indicate a foreign influence, contradict the Chinese nationalism that present ethnic minorities, including the Hui Muslims, as first and foremost ‘Chinese.’ Hence, Arabic was removed from the street signs; Halal restaurants had to cover up the Arabic signs meaning ‘Halal’ and replaced them with the Chinese term ‘qingzhen (清真).’

Furthermore, the Arabic and Islamic-style architecture that had attracted Middle Eastern countries’ attention was also removed and replaced with Chinese-style buildings. For instance, the Arab-style domes on top of the mosques were demolished and rebuilt into traditional Chinese-style roofs. The same process took place in the Hui Culture Park, where the comparison of satellite images of the park in December 2019 and October 2020 depicted the replacement of the Arabian style ‘mosque’ into a traditional Chinese style pagoda.

These policies on religious activities and symbols led to opposition from the local Muslim population. In August 2018, rumors about the impending demolition of the Weizhou Grand Mosque, which has Arab-style domes and minarets, caused protests by the local Muslim community opposing such attempts to eliminate Islamic symbols from the city. Although the mosque was not demolished, it was renovated to fit the Chinese orientation, in which the domes were replaced with traditional Chinese-style roofs, transforming the religious arena into an ostensibly ‘Sinitic’ space.

Dr. Haddad-Fonda, however, suggested that these policies on Islam may also have some appeal in Middle Eastern countries, as they represent how Islam has become an indigenous religion to China with local characteristics.

“This notion that Islam being Chinese is very attractive to people from a certain context,” said Dr. Haddad-Fonda, “the notion that the transnational manifestation and foreign influence of religion are subsumed and subordinated to indigenous religion that is in harmony with local characteristics and is under the control of the state – is really attractive.”

What China Can Learn from the 19th Century British Empire

Nonetheless, there remains a question over the consequences of such a Sinicization process. If China’s control over Islam or other religions continues in long-run, might Beijing lose the role of faith and culture as a pivot for China’s relationship with other regions worldwide? This is particularly important when considering that its BRI project includes infrastructural engagement in areas with a wide variety of cultures and religions. Instead of acting as a bridge connecting China with the Middle East, ‘Sinicized’ Islam might appeal to Chinese patriotism and nationalism, moving China further away from Arab countries. Thus, China should carefully consider religion’s unique role in providing strong narratives that appeal to international and domestic audiences.

When comparing Britain and China’s infrastructure projects in the Middle East, we see that both countries attempted to incorporate Islam into their outreach to the Muslim countries. Support for the Muslim population’s religious activities fostered the loyalty of these Muslims towards British and Chinese governance and closer ties with the Middle East region. While the British Empire supported Indian Muslims’ pilgrimage to Mecca, China’s outreach to the Middle East was facilitated with Hui Chinese Muslims as a representative of Islamic and Arabian characteristics of China’s ethnic diversity before 2018. These examples show that the two states considered the religious aspects of the cross-regional relationship.

By contrast, Islamophobia among Britain’s colonial rulers was the main factor that undermined the commitment between the local religious community and the state. A similar fear is also palpable in China today, where Beijing is concerned about religious and ethnic minorities differentiating themselves from the ‘Chinese identity’ and challenging Beijing’s rule. This anxiety led to the termination of the policy of promoting Islamic and Arab cultural influence in not only the city of Yinchuan but also other regions with religious populations. As seen in Beijing’s Xinjiang policy, China now prioritizes the assimilation of ethnic minorities into a single Chinese identity as the framework within which diverse cultures and traditions can express themselves. Similar to Britain’s Islamophobia, Chinese officials also fear increasing discontent among the Muslim ethnic minorities, including Hui and Uyghurs, towards the government.

As Dr. Haddad-Fonda suggested, however, the recent trend in the China-Middle East relations indicates that China’s Sinicization of Islam as an indigenous Chinese religion somehow appealed to the Middle East. China’s investment in the Middle East reached up to $93.3 billion in 2019, and the total trade volume between China and the Middle East also increased to $294.4 billion in the same year. A few Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt, even signed a letter to the UN Human Rights Council praising China’s repression of “terrorism, separatism and extremism,” and the restoration of safety and security. Although China was accused of suppressing domestic religious communities, it was able to get these Muslim countries’ support through the Chinese Islamic Association that controls how the Islamic narratives are delivered to the Middle East. State intervention in the practice of Islam is a matter of government policy in most Muslim countries, and these interventions typically aim to reduce radicalism, to reduce religiously-inspired political opposition, and to strengthen Muslim populations’ loyalty to the state. In that sense, these Muslim states recognise their affinities with China in its management of the Islamic religion.

Nevertheless, as Dr. Aydin’s lecture indicates, support for religious activities can bring the cross-regional relationship to the next level, and China cannot avoid religion’s role in its relations with the Middle East. The British Empire gained the Muslim population’s support due to both infrastructure construction and assistance for their religious obligations. Just as it contributed to the Muslim population’s loyalty towards the British Empire, the pilgrimage to Mecca is also an essential part of the historical China-Middle East relations. If China’s BRI aims to follow how Britain was able to expand its influence in the Middle East in the 19th century through its ‘Print and Steam Initiative,’ reconciling religious values into its infrastructure development will become more significant in China’s future relationship with the Middle East. These religious aspects of China-Middle East relations show that China should work on first embracing the religious traditions in its domestic sphere and then expand its pan-Eurasian connections. The Sinicization of the domestic Muslim population may be attractive to some Middle Eastern states, but it cannot mitigate the potential incompatibility originating from an absence of mutual understanding and cultural diplomacy. How long can Middle Eastern states maintain their favor for ‘Sinicized’ religion?

Hence, although the economic incentives of the BRI draw the Middle Eastern countries towards engagement with China, the religious dimension of the relationship with the Middle East must not be neglected. China can learn how the British Empire secured the Muslim population’s loyalty before the Balfour Declaration. If China’s nationalism and Sinicization policy continues to raise anxiety among Muslims in China and beyond, it may face the same dilemma as the contradiction between the British Empire’s Islamophobic governors and the world’s largest Muslim population. Thus, religiosity will undoubtedly be a persistent factor in the future of the BRI.

*About the author: Seong Hyeon Choi studied a Master of International Public Affairs at the University of Hong Kong and is currently working as an intern for ASIAR- Asian Religious Connections, a research cluster under the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Hong Kong.

Think one of the differences between the two initiatives is the military capability. The British military supremacy guaranteed successful construction of infrastructure under its sphere of influence and its ability of handling political unstability in the region, providing confidence to the locals in cooperating with or working for the British. For China, even though it has the economic capability of constructing infrastructure in the region, it lacks military supremacy to handle regional instability, considering the challenging political landscape in the Middle East following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the retreat of the colonial powers, which is one of the challenges China has to solve before it further advance the initiatives, for without a stable political environment, any investments or cooperation will be regarded as high risk.