New Delhi’s Soft Power Push – Analysis

Under Modi, India cultivates and promotes soft power of Bollywood, Sanskrit, yoga and democracy.

By Harsh V. Pant*

During his travels, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi makes a point of promoting India’s soft power – including Bollywood, Sufi music and yoga as well as shared heritage in art, architecture, cuisine and democratic values. It’s too early to assess if India’s efforts are having any substantive impact in meeting the nation’s foreign policy objectives, but for the first time a coherent effort is underway to raise India’s brand value abroad. This is likely to have significant implications for the conduct of Indian diplomacy and the broader role of India in global politics in the coming years.

Releasing its global ranking of soft power, the communications and public relatons consultancy Portland suggests “Modi’s India is definitely a soft power player to watch in the years ahead.” While India does not figure in a list of top 30 countries in terms of soft power, the new effort underlines Modi’s use of social media to engage, inform and encourage participation on both foreign- and domestic-policy fronts.

Previous Indian governments recognized the value of soft power to further India’s foreign policy goals, but the attempts were largely ad hoc. Under Modi, India is taking a strategic approach towards using its soft-power resources to enhance the nation’s image abroad, even as soft power’s role in global politics is under debate. Consider:

• In July, Modi underscored spiritual linkages between India and Central Asia, marking a contrast with growing extremism around the world, suggesting that “the Islamic heritage of both India and Central Asia is defined by the highest ideals of Islam – knowledge, piety, compassion and welfare.” By emphasizing India’s multicultural heritage, Modi undercut prevailing criticisms about his ideological leanings as a Hindu nationalist.

• India’s External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj was keynote speaker for a June Sanskrit Conference in Bangkok. She spoke in Sanskrit to more than 600 experts from 60 nations, describing the language as “modern and universal,” one the gathering should propagate. Underlining the contemporary relevance of the ancient language, Swaraj argued that proficiency in the language could “go a long way in finding solutions to contemporary problems like global warming, unsustainable consumption, civilizational clash, poverty, terrorism.” It was the first time an Indian minister of Swaraj’s rank attended the World Sanskrit Conference outside the country since the group was organized in Delhi in 1972. Perhaps taking a cue from China with its burgeoning Confucius Institutes, the Modi government is taking steps to promote the language internationally with a $20,000 International Sanskrit Award to scholars making significant contributions to the language, institution of fellowships for foreign scholars conducting research in India in Sanskrit language or literature, and opportunities for new learners to pursue courses or research in India.

• Yoga may be India’s most successful and popular soft-power tool. Modi led thousands in a mass yoga program in New Delhi on June 21, the first International Yoga Day. Modi had lobbied the United Nations and managed to win the support of 175 member states at the General Assembly for the resolution setting an international day of yoga. Yoga events were held in 251 cities across six continents with 192 countries participating.

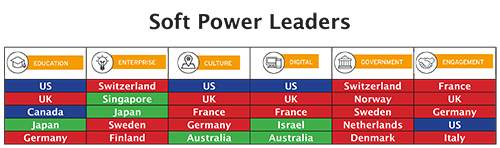

Race for soft power: Portland examined 50 nations and identified the world’s 30 soft power leaders; here, the leaders in six areas with North America in blue; Europe, red; Asia and Pacific, green (Data: Portland Soft Power 30)

India’s soft power worked its magic before without much government support. This is most notable in the case of Bollywood – the world’s largest film industry in terms of the number of films produced. Indian movies and music are watched and enjoyed in large parts of the world from the Middle East and North Africa to Central Asia. Yet Bollywood trails behind Hollywood in terms of its global reach. Previous governments did create new structures such as a new Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs in 2004 to tap into the growing influence of Indian expatriates and a public policy division within the Ministry of External Affairs in 2006 to enhance cultural exchanges in support of official diplomatic engagements. Yet so far there’s little evidence to suggest that India, for all its many soft-power advantages, has made a dent in global public opinion. According to 2013 Pew Global Attitudes survey, fewer than half, or 46 percent, Americans have a favorable impression of India. Compared to the British Council, Alliance Française and even the Confucius Institutes, the performance of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, with centers in about 35 countries and aimed at promoting Indian culture, has been lackadaisical. India has failed to build its brand value abroad.

Recognizing this, the Modi government seems keener than its predecessors to leverage India’s multifaceted soft-power resources from spiritualism, yoga and culture to its democratic ethos in the service of Indian interests.

This is a critical phase in the debate on soft power’s role in global politics. For much of the last decade, China has invested in trying to project an image of a peaceful rising power. Many western observers were in thrall of so-called Chinese success in enhancing its brand value across the globe, but especially in Asia – with its Confucius Institutes, extravagant Olympics displays and rhetoric of a peaceful rise. There are more than 480 Confucius Institutes around the world with plans to expand that number to 1,000 by 2020.

But Beijing’s aggressive posturing on territorial issues in the East and the South China Seas threaten to tatter that image as global analysts tend to emphasize the nation’s unabashed use of its growing economic and military heft to secure its interests.

And there is a broader debate whether soft power holds any lasting, tangible value in a today’s milieu when revisionist powers like China and Russia are threatening the global order and the rise of extremist groups such as the Islamic State makes hard power ever more attractive and necessary.

The Modi government’s attempt to leverage soft power is meant to position New Delhi at a critical juncture while much of the world continues to regard India as a relatively tolerant and multicultural democracy with a largely benign international influence as well as an emerging economy with the potential of becoming a huge economic success story. India’s cultural links with East and Southeast Asia as well as the Middle East and Central Asia underscore India’s centuries-old role as the font of various religions and cultures. If Buddhism spread from India to China and beyond, Hinduism traveled to Southeast Asia, and Islam linked India to Central Asia.

In diplomatic engagements around the world, the Modi government consistently underscores India’s democratic credentials. At a time when economic turmoil in the West is generating apprehensions about the value of democracy, India continues to signal the virtues of a democratic political order. The Modi government is unlike its predecessors, ambivalent about focusing on democracy, and instead the prime minister emphasizes shared political values to strengthen ties with the West and democracies in Asia. Even when he visited Mongolia, Modi praised the nation as the “new bright light of democracy” in the world, thereby marking a distinction between the democratic values of India and Mongolia and those of authoritarian China. The Modi government is striving to not only revive national pride in the country’s ancient values, but also enhance India’s hard power by using its soft-power advantages.

Sustained effort is needed by New Delhi to succeed as global soft power. India today is more confident about projecting its past heritage as well as its contemporary values on to the global stage, and this can only be good news for the global order in dire need of positive exemplars. An economically successful pluralistic democracy is the best antidote to authoritarianism and extremism rampant around the world.

*Harsh V. Pant is professor of international relations at King’s College London and the author ofIndia’s Afghan Muddle (HarperCollins). Read “The Soft Power 30: A Global Ranking of Soft Power” from Portland.