Spain’s Merchandise Exports Notch Up Yet Another Record – Analysis

By William Chislett*

Spain’s exports of goods rose in 2016 for the seventh year running, defying expectations that they would tail off as the economy recovers and domestic consumption picks up.

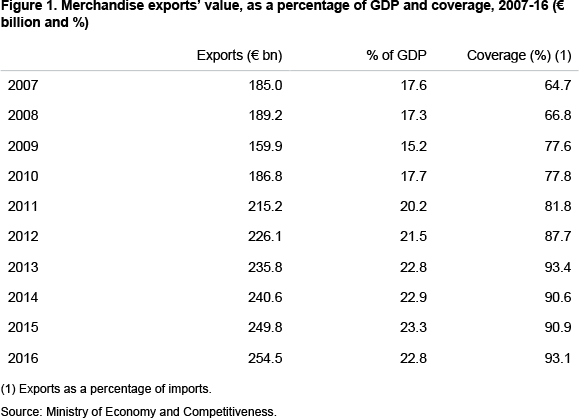

Exports were 1.7% higher than in 2015 at €254.5 billion and imports 0.4% lower at €273.3 billion (see Figure 1). As a result, the trade deficit fell 22.4% to €18.7 billion, the second lowest figure since 1997. Coupled with a buoyant tourism year (75.3 million visitors and spending of around €77 billion), the better trade figures helped to generate another current-account surplus (estimated at 2% of GDP). From 1990 to 2012, Spain had current-account deficits every year.

The coverage ratio (the percentage of imports covered by exports) was 93.4%, up from 66.8% in 2008 when the economy went into a prolonged decline, which ended in 2014 with anaemic growth. Since then the economy has continued to grow, but only at some point this year will the GDP level return to its pre-crisis level.

The €65.3 billion rise in exports since 2008 is a striking achievement, given that Spain is not known for being a country of export prowess. Faced with plummeting demand from consumers, companies and the government, companies have had no alternative but to seek out markets abroad or in some cases face going to the wall, particularly small and medium-sized ones. Exports thus became a matter of survival.

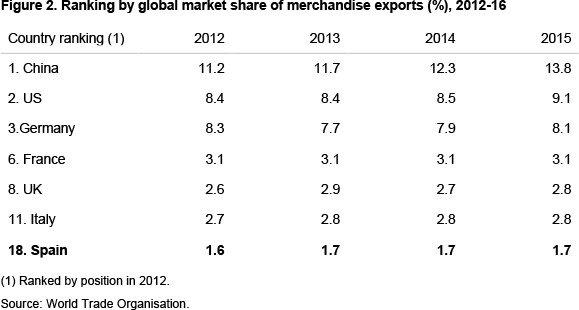

Spain achieved this, despite the rise of countries such as China and India. Its share of world trade held steady between 2013 and 2015 (latest year available) at 1.7% (see Figure 2).

Export growth, spurred by productivity gains and restored competitiveness, has been faster than powerhouse Germany’s, France’s and Italy’s, albeit from a smaller base.

The sharp rise in Spain’s unemployment rate from 8% in 2007 to a peak of 27% in 2013 (18.6% at the end of 2016) has reduced wages in real terms and lowered unit labour costs. The government’s 2012 labour-market reforms have enabled companies to negotiate wages and working conditions more flexibly, while the euro’s depreciation against the US dollar has benefited Spain’s exports to non-euro zone countries.

These factors, in turn, have spurred foreign direct investment in Spain, some of which has gone to major exporting industries, notably the automotive industry (which accounted for 17.7% of total exports last year).

One sector that has made particularly impressive strides is food and drink which, together with tobacco, generated almost 17% of total exports, not far from the automotive industry, all of whose car producers, unlike food and drink, are in multinational hands. Spanish ham, for instance, is beginning to gain popularity in China and olive oil in the US.

The number of companies exporting rose from 109,363 in 2010 to 147,334 in 2016 (down from a peak of 151,160 in 2013), 47,768 of whom were regular exporters (more than four consecutive years), 23.3% higher than in 2010. Many companies that started exporting after 2011, at the height of Spain’s recession, are still exporting. This is a significant structural improvement, particularly given the fixed costs companies incur when they enter foreign markets, and one that needs to be maintained if Spain is to keep on improving its export performance.

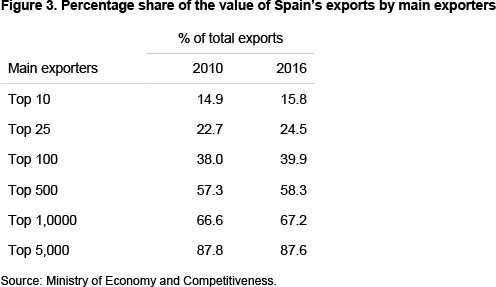

A very small number of exporters, however, still account for a big share of exports. The 10 largest exporters accounted for 15.8% of total exports last year, a larger share than in 2010 (see Figure 3).

The high export concentration is due to the high atomisation in Spanish companies: their average size is a fraction compared to that of many other developed economies. This atomisation limits export capacity as it is widely accepted that firm size is the largest single determinant for Spanish companies to start exporting. Larger firms tend to have higher productivity growth, so their unit labour costs typically rise less than for smaller and less productive firms. Critical mass also enables companies to access funding from banks and capital markets.

In order to build on its export success, Spain needs more medium-sized and large companies. Almost 40% of employment in Spain is generated by large and medium-sized companies, which represent, respectively, 0.1% and 0.7% of the total number of companies, while the remaining 60% of jobs are generated by 99% of companies. According to the OECD, more than 40% of workers in Spain are hired by firms with fewer than 10 employees compared to 29% in France, 19% in Germany and 11% in the US.

The challenge for Spain is to find ways to encourage companies to grow in size, without which the export performance will be difficult to sustain.

About the author:

*William Chislett, Associate Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute | @WilliamChislet3

Source:

This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute