Great News From Guantánamo: Three ‘Forever Prisoners,’ Including 73-Year Old Saifullah Paracha, Approved For Release – OpEd

In extremely encouraging news from Guantánamo, three men have been approved for release from the prison by Periodic Review Boards, the high-level government review process established under President Obama.

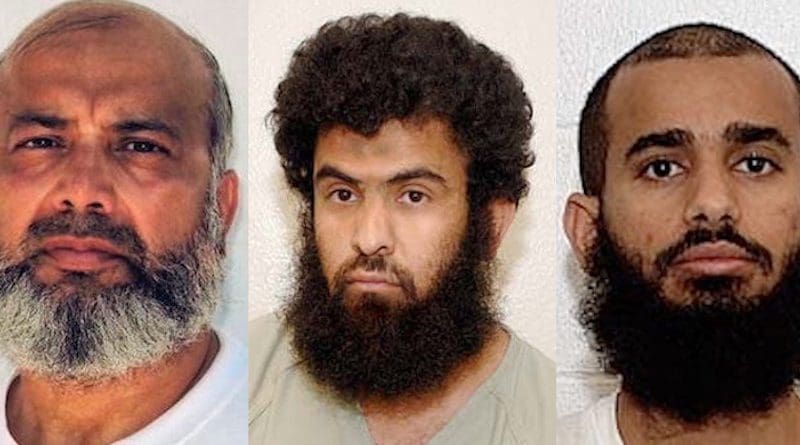

The three men are: 73-year old Pakistani citizen Saifullah Paracha, Guantánamo’s oldest prisoner; Abdul Rahim Ghulam Rabbani, another Pakistani citizen who is 54 years old; and Uthman Abd al-Rahim Uthman, a 41-year old Yemeni. All have been held without charge or trial at Guantánamo for between 17 and 19 years.

Between November 2013 and January 2017, when President Obama left office, the Periodic Review Boards — consisting of representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — reviewed the cases of 64 prisoners, to ascertain whether or not they should still be regarded as a threat to the US, and, in 38 cases, recommended the prisoners for release. All but two of these men were released before the end of Obama’s presidency.

For the 26 other men, however, who included Saifullah Paracha, Abdul Rahim Ghulam Rabbani and Uthman Abd al-Rahim Uthman, the board’s refusal to approve them for release left them in a shameful limbo. Aptly described, by Carol Rosenberg (then with the Miami Herald, now with the New York Times) as “forever prisoners,” they continued to have their cases reviewed, but found themselves unable to meaningfully challenge the positions taken by the board members — a situation that ossified into complete indifference from the boards during the four long years of Donald Trump’s presidency, when the official policy regarding the prison, as expressed in a tweet posted by Trump even before he took office, was that “[t]here must be no more releases from Gitmo.”

Under Trump, only one prisoner was released from Guantánamo (a Saudi who had agreed to plea deal in his military commission trial, and was repatriated to continued imprisonment in his home country), and the “forever prisoners” became so disillusioned with the PRBs that they largely boycotted them. It was not until the dying days of Trump’s presidency that one of the 26 “forever prisoners” was approved for release, and, just as Biden took office, the Pentagon filed charges against three others, leaving 22 “forever prisoners” in his control on January 20.

The decisions announced on Monday in the cases of Saifullah Paracha, Abdul Rahim Ghulam Rabbani and Uthman Abd al-Rahim Uthman are promising because they were the first three cases considered by the PRBs after Biden won the Presidential Election in November. Paracha’s took place on November 19, Rabbani’s on January 26, and Uthman’s on February 23.

In all three cases, the boards are to be commended for having finally taken on board a need to reconsider the prisoners’ cases, and not simply to reflexively reiterate the positions taken when their cases were first reviewed under Obama, which were then repeated under Trump.

In part, this change has come about because of the change in leadership in the White House. While Trump had no interest in releasing anyone from Guantánamo, senior officials and spokespeople in the Biden administration have already acknowledged that Guantánamo should be closed, and have spoken of establishing a “robust” interagency review of the prison, and their “intention” to close it before the end of his four years in office.

In addition, significant players in the machinery of US government have also spoken out about the need for the US to finally bring to an end the indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial to which the “forever prisoners” have been subjected, with, for example, 24 Senators writing to Biden last month, calling for the closure of the prison, and demanding that the men still held must either be charged or released.

Most of all, however, what the decisions to recommend the release of Saifullah Paracha, Abdul Rahim Ghulam Rabbani and Uthman Abd al-Rahim Uthman reveal is how, once long-held and rigid US government positions are encouraged to be reassessed, as would seem to be the case under President Biden, the basis for the continuing imprisonment of some of Guantánamo’s “forever prisoners” is either, very fundamentally, non-existent, or has demonstrably failed to take account of changing circumstances.

Saifullah Paracha

Throughout his long imprisonment without charge or trial, Saifullah Paracha, who has serious health issues and has had three heart attacks at Guantánamo, has also been the very definition of a model prisoner, respected and admired by his fellow prisoners and by the authorities, and adopting an important role as a mentor to younger prisoners, who have often — and quite understandably, as I see it — struggled to maintain a positive outlook when imprisoned, year after year, in grotesquely challenging and fundamentally lawless circumstances.

Despite this, however, his ongoing imprisonment has hinged on US allegations of his involvement in terrorism, even though it has become increasingly obvious over the years that these claims have never been anything more than a mirage.

A successful businessman in Pakistan, who also had business interests in the US and had lived there in the 1980s, he was introduced to Osama bin Laden during a business trip to Afghanistan in 1999 or 2000, and expressed an interest in featuring him in a TV programme, giving him a business card that, in the summer of 2002, led to him being approached by another man who claimed to be interested in the proposed TV show. This man and two colleagues subsequently persuaded Saifullah and his son Uzair to help them with various US immigration issues, some involving financial transactions, little realizing that the men they were dealing with were members of Al-Qaeda — Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Ammar al-Baluchi and Majid Khan — and that they were attempting to arrange a bomb plot on the US mainland.

Saifullah was kidnapped, while on a business trip in Thailand, in August 2003, and was held and tortured in CIA “black sites” until his transfer to Guantánamo in September 2004. Uzair, meanwhile, was arrested in the US, and tried and convicted in 2005, receiving a 30-year sentence for “providing material aid and financial support to al-Qaida terrorists” in 2006. In July 2018, however, the judge in his case, Judge Sidney H. Stein, threw out the conviction and ordered a retrial, “after concluding that allowing the existing conviction to stand would be a ‘manifest injustice,’” as I explained in an article last year.

As I also explained, “Judge Stein correctly asserted that the critical question had ‘always been whether Paracha acted with knowledge that he was helping Al Qaeda,’” and in ordering a retrial he recognized that Uzair had made false statements after his arrest, when he had not been given his Miranda rights, through “a combination of fear, intimidation and exhaustion.” Crucially, he also recognised, as the New York Times described it, that, since the initial trial, “new evidence had come to light: statements not only by Mr. Khan and Mr. al-Baluchi, but by the self-described architect of the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks — Khalid Shaikh Mohammed,” which were “made before military tribunals or in interviews with federal agents,” and which “directly contradict the government’s case” that Uzair Paracha “knowingly aided Al-Qaeda.”

As the Times proceeded to explain, Majid Khan “told the authorities that he had never disclosed his Qaeda ties to Mr. Paracha, whom he described as innocent,” while Khalid Sheikh Mohammed “openly confessed his responsibility for dozens of heinous crimes and terrorist plots,” but “never mentioned Mr. Paracha or his father.”

Because of this new evidence, Judge Stein noted that Uzair Paracha could “credibly ask the jury” to infer his innocence and “lack of involvement in the operations discussed,” but when it came down to it the government refused to proceed with a retrial, and Uzair was flown back to Pakistan in March last year, a free man.

That should have led to Saifullah’s release too, but as I explained at the time, “there is no guarantee that his father will also be released, because, although the profound doubts about the reliability of those who, under duress, accused him of being knowingly involved with Al-Qaeda are just as applicable to the case against Saifullah Paracha, the horrible truth about Guantánamo is that suspicions are regarded as far more compelling than evidence.”

That position, thankfully, has now been abandoned by the US authorities, and it is to be hoped that he will soon be released, to be reunited with his family. On Monday, the Associated Press reported that his attorney, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, “said she thinks he will be returned home in the next several months.” As she explained, “The Pakistanis want him back, and our understanding is that there are no impediments to his return” — although it should be noted that US law currently demands that Congress must be given 30 days’ notice before any Guantánamo prisoner is released.

Abdul Rahim Ghulam Rabbani

In the case of Abdul Rahim Ghulam Rabban, a Pakistani national of Rohingya origin, who was born and raised in Saudi Arabia, the board’s decision to approve him came as a complete surprise.

Rabbani — with his brother, who is also still held as a “forever prisoner” — was seized in Karachi in September 2002, and was subsequently held and tortured in a CIA “black site” in Afghanistan before his transfer to Afghanistan in September 2004. In his PRBs, the US authorities have described him as “an al-Qa’ida facilitator,” recruited by his brother, who worked directly for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and whose work was “focused primarily on providing logistic support and operating an al-Qa’ida safe house in Karachi,” adding, however, that they also consider that “he probably did not have specific insights into al-Qa’ida’s operational plans.”

The recommendation for Rabbani’s release may well have come about because of his remorse for his past actions. As his attorney, Agnieszka Fryszman, explained at his PRB in 2016 (which nevertheless led at the time to a recommendation for his ongoing imprisonment), she described him as “a simple man,” who is “not well educated,” and who, moreover, is thoroughly remorseful for his actions assisting al-Qaeda members, which he did solely to support his family. As Fryszman stated, he “has never been an ideologue or jihadist,” and, in ten years of meeting with him, “he has never once — not even a single time — expressed any anger or animus towards the United States or towards any American citizen.” It was also noted that he has been well-behaved at Guantánamo, that “he sweeps up and cleans his block,” and that he “stays away from conflict,” and also that there is a plan for his release co-ordinated with his very supportive family members, either in Pakistan or in Saudi Arabia.

Uthman Abd al-Rahim Uthman

The third man whose release has been recommended, Uthman Abd al-Rahim Uthman, a Yemeni citizen, is one of a number of foot soldiers for the Taliban who are still held as “forever prisoners,” even though the overwhelming majority of their fellow foot soldiers were released many years ago.

For his PRBs, the US authorities have persistently claimed that he was a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden — one of a group of men captured crossing from Afghanistan to Pakistan in December 2001, who were described as “the Dirty Thirty” — even though this has never been a credible claim, because most of the men were very young, and recent arrivals in Afghanistan, whereas bin Laden’s actual bodyguards were generally battle-hardened Egyptians. Moreover, as with the foot soldiers in general, almost all of the “Dirty Thirty” were released from Guantánamo many years ago.

In Uthman’s case in particular, a crucial development in debunking the claims about his role as a bodyguard took place eleven long years ago, when a judge in the District Court in Washington, D.C., Judge Henry H. Kennedy Jr., reviewing his habeas corpus petition, refused to accept claims that he was a bodyguard for bin Laden because they had been made by two other prisoners — Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj and Sanad Yislam Ali al-Kazimi (both still held as “forever prisoners”) — whose testimony was unreliable because of “unrebutted evidence in the record that, at the time of the interrogations at which they made the statements, both men had recently been tortured.” Back in 2010, Judge Kennedy granted Uthman’s habeas corpus petition, but in the shameful way that so much business regarding Guantánamo has been conducted over the years, the Justice Department, under President Obama, appealed, and in 2011 judges in the court of appeals, who were demonstrably supportive of Guantánamo’s continued existence, reversed Judge Kennedy’s ruling, with law professor Jonathan Hafetz concluding that their ruling endorsed “indefinite detention based on suspicion or assumptions about a detainee’s behavior.”

At Uthman’s hearing, in February, Beth Jacob, who represents a number of Guantánamo prisoners, and has been his attorney since 2019, provided a good explanation of why Uthman should be released, telling the board members, “Over the past year and a half, I have gotten to know Mr. Uthman fairly well. Before the pandemic, I met with him more than half-a-dozen times. In the past year, when I could not travel to Guantánamo, I have spoken with him monthly. He is thoughtful, polite and open-minded. He has a very dry sense of humor. He is eager to learn and has taken advantage of the opportunities at Guantánamo to take classes, ranging from business to art to English. He has worked hard at these studies.”

She added, “Mr. Uthman’s mindset and attitudes have completely changed from his early 20s. He harbours no anti-American or anti-social attitudes. He has never been resentful because of his imprisonment or hostile to the United States in any of our many conversations. He has been among the most compliant detainees throughout his lengthy detention. He continues to work within established processes and procedures such as the Board, despite his intense disappointment at its decisions. Over his 19 years in detention, he has grown up, matured and educated himself, and learned from past mistakes. I hope this Board will agree that he poses no threat to the United States — or anyone else — and should be cleared for release.”

So what now?

Despite the welcome news that these three men have finally been approved for release — and Shelby Sullivan-Bennis’s hopes that Saifullah Paracha will be released within a few months — it is important to remember that, even before these decisions were announced, six other men, out of the 40 prisoners still held in total, are still held despite being approved for release, and President Biden needs to take urgent action to appoint someone to deal with their long-delayed release from the prison, as well as the release of Saifullah Paracha, Abdul Rahim Ghulam Rabbani and Uthman Abd al-Rahim Uthman, most obviously by reviving the Office of the Special Envoy for Guantánamo Closure, which was established under President Obama, but dismantled under Donald Trump.

It also remains to be seen whether these decisions mark the start of a trend within the PRBs for board members to recognize the changing situation regarding Guantánamo under Joe Biden, in which, as noted above, prominent voices are increasingly calling for prisoners to either be charged or released, to bring to an end the fundamentally unacceptable policy of indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial.

It would particularly make sense for other foot soldiers to be approved for release in light of the Uthman decision, and President Biden’s recent promise to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan by the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks — men like Moath al-Alwi and Khalid Qassim, for example — but if progress is genuinely to be made in either charging prisoners or releasing them, then those decisions are either going to have to be taken by the PRBs, or in the courts, where Attorney General Merrick Garland could instruct the Justice Department to no longer challenge prisoners’ habeas petitions.

One way or another, though, long-standing contentious cases — like those of torture victim Mohammed al-Qahtani and Afghan prisoner Asadullah Haroon Gul — need to be addressed, as well as the other cases that few people have been paying attention to over the years — of the 15 other “forever prisoners” not discussed above.

The PRBs are still ongoing. Two took place, last month and in March, that have not yet delivered rulings, another took place yesterday, and five others are scheduled to take place over the next three months, which those of us who care about the closure of Guantánamo need to keep under close scrutiny.